|

Jahan Choudhry Paul Robeson is an example of an outstanding fighter for world peace, who sacrificed fame, fortune, and health for the future of humanity. We celebrate Paul Robeson’s 125th birth year at a time when the US government is waging its most dangerous war since the Second World War. At the same time the US population has a historic anti-war and anti-government feeling. Events since the start of 2023 especially the Rage Against the War Machine March held in February signal the possibility of a new organized movement against the US administration’s criminal war policies. However, the task of building an effective peace movement will only be successful if it is anchored in the example of Paul Robeson.

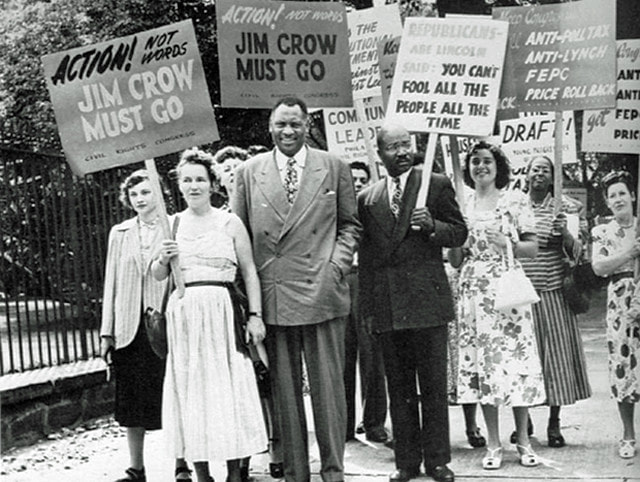

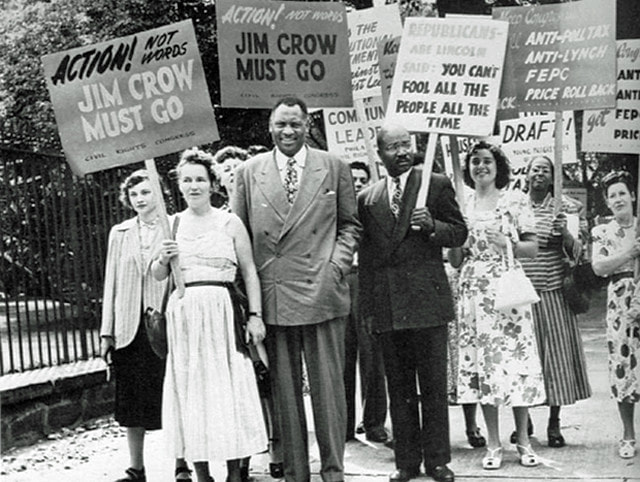

At a time when activists working for labor and civil rights were compromising with the Democratic Party administration of Harry Truman, Robeson refused to compromise and stood with world humanity. He did this despite the cost it put on his career as a performer and artist. He became a co-founder of the World Peace Council which sought to build an opposition to the West’s policy of cold war confrontation and a nuclear arms race by bringing together progressive Americans with others from around the world including the Soviet Union. Upon receiving the Stalin Peace Prize in recognition of his brave stance for world peace in 1953 Robeson said: “The American Peace movement reached out its hands across the borders to join with the millions of peace fighters in the world peace movement. Gradually it has become crystal clear that the mighty strength of the world movement representing peoples of all lands is strength for us here. As Americans, preserving the best of our traditions, we have the right—nay the duty—to fight for participation in the forward march of humanity. We must join with the tens of millions all over the world who see in peace our most sacred responsibility. Once we are joined together in the fight for peace we will have to talk to each other and tell the truth about each other. How else can peace be won?... In this framework we can make clear what co-existence means. It means living in peace and friendship with another kind of society—a fully integrated society where the people control their destinies, where poverty and illiteracy have been eliminated and where new kinds of human beings develop in the framework of a new level of social living. The telling of these truths is an important part of our work in building a strong and broad peace movement in the United States.” The media colluded with the US state to slander and then ignore Robeson’s activism in press coverage. Though his activism received little coverage outside of the black community and the Communist movement in the US, he became a symbol to people throughout the world of a principled American. It is very interesting to note that poems were written about him in many languages including Turkish, Russian, Chinese, Urdu, Bengali. As W.E.B. Du Bois said at a rally in support of Robeson in Harlem: “He is without doubt today, as a person, the best known American on earth, to the largest number of human beings. His voice is known in Europe, Asia and Africa, in the West Indies and South America and in the islands of the seas. Children on the streets of Peking and Moscow, Calcutta and Jakarta greet him and send him their love. Only in his native land is he without honor and rights.” Du Bois' statement points us to how famous Robeson was prior to and despite the repression he faced. After many years of litigation he received his passport in 1958 in time for him to resume his travels. Having opposed the Korean War, he strongly opposed US policy in Indo-China, and also stood in solidarity with the Cuban Revolution of that period. According to his son after concluding a concert tour in London in 1961, he traveled to Moscow in order to transit to Cuba to show his support for the revolutionary Castro government. This was bound to be an embarrassment to the US deep state which had already made plans for the Bay of Pigs invasion. It was in Moscow that he was first targeted with a potent dose of LSD, which according to his family drove him to attempt suicide. His son maintained that this was part of the CIA’s MKULTRA drug program, which recent evidence has shown weaponized LSD to control human behavior. Doctors in Moscow advised him to return to Harlem where he would be in a healthy environment and protected from the wrath of the intelligence agencies. Unfortunately he would be hit with two more devastating drug attacks in Britain and the United States. The final one left him damaged but he was conscious enough to make the decision to retire from public view, with the hope that his public image would stay intact. He lived the remaining 13-14 years of his life in his sister’s house in West Philadelphia, rarely receiving visitors, not even appearing at a 75th birthday celebration organized for him at Carnegie Hall though he sent a taped message saying: "Though I have not been able to be active for several years, I want you to know that I am the same Paul, dedicated as ever to the worldwide cause of humanity for freedom, peace and brotherhood.” Though the repression of McCarthyism and the Red Scare meant he was not known very well by the generation that came after him or the generations since, he has lived on in the black community and in groups dedicated to peace and justice. Dishonest intellectuals have tried to de-radicalize Robeson and promote petit bourgeois theories of “woke” anti-racism in his name. This woke agenda seeks to separate his struggle against racism from his struggle against imperialism. These theories are all cynical ploy by a US elite in crisis to rebrand and reconsolidate itself. Robeson was an avowed enemy of imperialism and of the deep state. He gave his all to the struggle against the permanent warfare state, including the struggle against NATO. Just as he stood up to the reactionary in liberal clothing, Harry Truman, he would stand up to Biden today, who is in many ways pursuing a foreign policy against Russia that is reckless and even insane. If he were alive today he would stand against witch hunts like Russiagate just as he stood against McCarthyism and the Red Scare. He would stand against the collusion of intelligence agencies with big tech and the media to repress anti war voices. As he stood with the working class in every struggle they waged, he would reject the characterization of all those who refuse to vote for warmongers as deplorables or fascists. In his life he believed that if given the choice, the American people would always choose peace over war. Further, he believed that racism was embedded in the blue-blooded elites, not the working class. If Robeson were alive today, he would call to organize the whole US working class, black, white and otherwise against the current administration’s policy of immiserating the working poor to fund a Ukraine proxy conflict. He would call for the dismantling of not just NATO but all 800 military bases around the world as well as the cutting down of our criminally high defense budget. He would call for the release of political prisoners, whistleblowers and journalists like Julian Assange victimized by the US deep state. It must be said in no uncertain terms that Robeson would see the significance of this country’s main opposition leader, the former president of the US, Donald J. Trump. Trump has been outspoken in opposition to the Ukraine War and both he and the movement behind him have become targets of the national security state. As Robeson fought for black-white unity for peace in his day, he would be in the thick of seizing this moment to build a peace movement of a new type across racial and partisan lines; a coalition of the dispossessed to stop this administration’s insane warmongering and to reconstruct America’s economy on a peace basis. As he stood with Bandung and anti-colonialism in Asia and Africa, he would stand with the emergence of BRICS. He would stand in solidarity with the peaceful rise of Asia and the possibility of a new and sovereign Africa, which signals a move from a Western world order to a human one. Robeson’s significance for today animates the possibility of popular resistance to the Biden regime and the deep state. Events since the start of 2023 show the possibility of a new peace movement emerging, most significantly with the holding of the Rage Against War Machine (RAWM) march held at the US capital in February which deliberately crossed the partisan political lines imposed on the people by the US elites. A so-called Left-Right Alliance, the march was organized by the Libertarian Party and the People's Party. It included speakers from both the Democratic and Republican parties as well as independent journalists. The march broke with the kind of anti-war organizing that has occurred since 9/11, in which sectarian groups have used social issues like gender and sexuality as a litmus test to exclude large sections of the US people from participating. Even more significantly the march organizers refused to bend to liberal anti-Trump politics, which seeks to exclude the Trump movement’s anti-war voter base from the peace movement. Thus, the march became a target of attack for the small and sectarian left organizations and anti-war coalitions which criticized it for supposedly playing into the hands of white supremacists and racists. The unique composition of the RAWM was matched with an extremely radical set of 10 demands. Among these were “Not One Penny More for Ukraine”, “Negotiate Peace”, “Stop the War Inflation”, “Slash the Pentagon Budget”, “Abolish the CIA and Military-Industrial Deep State”, and “Abolish War and Empire”. These set of demands clearly link the Ukraine War to the broader struggle against the permanent warfare state and the imperialist ideology perpetuated by the ruling elite. Though the turnout numbers were likely 2-3,000 people, with a much larger number watching on social media and participating in solidarity marches around the country, the ideological strength of the march meant that it punched above its weight. An exemplary speech was delivered by former Democratic Congressman Dennis Kucinich who went on the offensive against a president from his own party. Kucinich took direct aim at the Biden administration for its bombing of the Nordstream pipeline, as revealed by Seymour Hersh, and said “we will not rest until you are held responsible by the Congress, the International Criminal Court, and the American people at the next election.” He criticized American elites foreign policy of continuing NATO expansion, which is bringing the world to world war in Ukraine and Taiwan. He took aim at the Biden administration’s anti-people domestic record as it related to the Covid pandemic and civil liberties. He even quoted a passage from the declaration of independence which reads: “That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” Other speakers echoed this feeling of revolt as well as spoke about the need for the US to seek collaboration with Russia and China to solve world problems, especially poverty. Kucinich’s speech shows the radical energy in the RAWM march attendees and how they are open to the project of a democratic remaking of US state and society. Though the turnout was largely made up of white Americans, the fact that increasing sections of White America are supportive of such radical demands is a major shift in US politics. It is clear that Robeson would stand with the RAWM, even as he would offer constructive criticism in engaging deeper with the African American community and world humanity. Robeson’s brand of anti-racism would never allow the struggle against racism to be misused to attack peace activism, especially at such a vulnerable time for world peace. Though Trump was not at the rally his opposition to the Biden regime’s policy loomed in the background. Since the march Trump has issued even more radical statements calling for the “complete dismantling of the neocon globalist establishment that gets us into endless wars.” In the same statement he also said that America’s real enemy is not Russia or China but its own “America last elites”. It is not a coincidence that soon after issuing this statement he was indicted by the Manhattan County District Attorney on an election finance technicality. Similarly, Pro-Trump House Republican Matt Gaetz publicly challenged the role of the United States Africa command (AFRICOM) and organized a resolution to withdraw US troops from the illegal occupation of Syria. At the end of April, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. officially entered the Democratic Party presidential primary on a populist platform. Having gained notoriety as an outspoken critic of Anthony Fauci and big pharma’s corrupt handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, RFK Jr also invoked the Kennedy legacy of his father and uncle in their opposition to the CIA and the military industrial complex in calling for an end to the Ukraine War and US militarism abroad. All of this indicates a furthering political crisis for the warmongering elites and the possibility of a consolidated political leadership with an alternative vision. Though much work remains to be done to solidify these parts into an ideologically clear whole, there is great reason for optimism that the American people can play a decisive role in the struggle for world peace. Thus, in his 125th birth year Paul Leroy Robeson stands tall as a model of what the people of his nation must strive to become in order to fulfill their highest aspirations for peace and democracy.

0 Comments

Neha Chivukula “And so by fateful chance the Negro folksong--the rhythmic cry of the slave--stands today not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side the seas…..it still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people.” -Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois [1] Paul Robeson was one of the greatest artists our world has ever seen. He was one of the greatest not just because he was a prolific singer and an actor but because of how he used his art to become one with the people of the world. Robeson believed that art and the artist cannot be separated from the struggle for humanity’s deepest strivings- freedom, peace, and dignity. In this fight, “the artist must take sides”. The moral imperative that Robeson felt as an artist reflected in the life he lived. He used his talents to further the cause of humanity and exemplified courage and a spirit of sacrifice that earned him the love of people worldwide. Once accepted as a talented artist by the US ruling class, when he used his art for the emancipation of his people, he was intensely persecuted. Despite many attempts by the American government to isolate Robeson and his ideas from the people, progressive humanity worldwide marched under the banner of his name Culture, as Robeson believed, originates within the masses of people and is a reflection of their aspirations and their history- that is, relationships between individuals of a society and between an individual and the environment. Thus, a people’s contribution to furthering human civilization is unique. Yet this culture, though unique in its character, can connect you with the universal -- it speaks of the suffering, the struggle of the people, their philosophy of life and their hopes and aspirations. Speaking of the music of his own people, the Black Spirituals, Robeson said: “…this enslaved people, oppressed by the double yoke of cruel exploitation and racial discrimination, gave birth to splendid, inspired, life-affirming songs. These songs reflected a spiritual force, a people’s faith in itself and a faith in its great calling; they reflected the wrath and protest against the enslavers and the aspiration to freedom and happiness. These songs are striking in the noble beauty of their melodies, in the expressiveness and resourcefulness of their intonations, in the startling variety of their rhythms, in the sonority of their harmonies, and in the unusual distinctiveness and poetical nature of their forms” [2]. These songs of struggle spoke to millions of oppressed people worldwide and inspired many of the anti-colonial movements. Robeson said: "I have sung my songs all over the world and everywhere found that some common bond makes the people of all lands take to Negro songs as their own." [3] Robeson saw the Black struggle as part of a larger struggle of darker humanity against exploitation and for freedom and positive peace. Robeson’s view of art and culture is deeply philosophical. For him, art and culture rooted in the people are concrete and depict an inner emotional or intuitive capability which adds vitality to the creation. It is the interaction of the incalculable human capacity with the physical reality that gives birth to something that speaks to the human spirit. This expression of the human spirit is what binds all art and music originating in the East. Robeson asserted that the people of Africa in particular, and Afro-Asia have made some of the greatest contributions to furthering human civilization, particularly in art and culture. It is only in applied science that the West rose ahead and claimed its superiority on this basis. However, this excessive emphasis on applied science has led to an abstract intellectualism and hollowness among the Western bourgeoisie. In developing his intellectualism, the Western bourgeois man lost touch with his creative side. This meant that Western art got trapped in unrooted abstractions that do not speak to an inner human striving and are often lifeless. Robeson said: “A blind groping after Rationality resulted in an incalculable loss in pure Spirituality... we grasped at the shadow and lost the substance and now we are altogether not clear what the substance was.” [4] Culture, through its reflection of material and spiritual conditions of a people, serves as a touchstone to assess the historical claims made by imperialism. Robeson argued that Africa with all the linguistic and artistic diversity represented a highly advanced civilization similar to other civilizations, like China. He recognized that imperialism relied on denying that darker humanity, especially Africa, had made any contributions to the world and that they were “primitive” in order to justify the exploitation of the colonized people. The history and social roots of Black music and art were distorted to portray Black culture as imitative, and produced by people who were meek and submissive. So, he made it his mission to educate the world about the immense contributions that his people had made to the world. Robeson declared: “In my music, my plays, my films, I want to carry always this central idea; to be African. Multitude of men have died for less worthy ideals; it is even more eminently worth living for.” He urged Black people to not fall prey to the racist theories of inferiority of the African race and embrace their roots. He said: “He (American Negro) sees only the savagery, devil-worship, witch doctors, voodoo, ignorance, squalor and darkness taught in American schools. Where these exist, he is looking at the broken remnants of what was in its day a mighty thing; something which has perhaps not been destroyed but only driven underground, leaving ugly scars upon the earth’s surface to mark the place of its ultimate reappearance.” [5] He felt that only the Black man with his "immense emotional capacity" could revive and bring new life to the culture in America. But, if on the other hand, the Black man were to imitate the White society, he would lose the immense artistic wealth that his people had accrued over the course of history through struggle. Art and culture thus, represent a life-world-- a means of experiencing the universe or truth through subjective interpretation collectively. As art brings people closer to the human universal, it serves as the broadest approximation of truth. This collective quest for truth is not just determined by history but also determines what future the human civilization will move towards. It is this agency that revolutionary culture nurtures in people which allows them to see the sky of possibilities and hope and work towards a better future even when they are enveloped with dark and troubling times. According to Robeson, “the whole problem of living cannot be understood until the world recognizes that artists are not a race apart…Each man has something of the artist in him.” [6] The culture promoted by the ruling elite is contrary and opposed to revolutionary culture. It relies on a belief that the ability to see and appreciate beauty in art and music is inherited by a handful of people and the rest of humanity is viewed as “uncultured” and unworthy. This culture celebrates a life of materialistic indulgences and consumerism and upholds these as ideals worth aspiring to. Within this framework, the masses of people are portrayed as morally depraved without the right to claim their future. Such a culture tries to obscure the paths available for collective human struggle to reach a future where all human beings can express their maximum potential. It thrives by creating a nihilistic and grim view of the future that almost paralyzes people from engaging in any kind of struggle and makes them retreat into an individualistic life. Art and culture therefore cannot be separated from the ideologies that they represent. As Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois said in the Criteria for Negro Art, “all art is propaganda.” [7] The basis for evaluation and appreciation of all art must be rooted in an understanding of morality and the contribution of art to the struggle of people. One cannot merely appreciate art or culture without embracing the people who produce it or the ideals that shape it. Robeson criticized the white “cultured” elites of America who claimed to appreciate or even appropriated the art produced by the Black people but refused to recognize the Black man as a human being. Racial discrimination and segregation continued to oppress the Black population. The music and art that was produced during the Harlem Renaissance was highly appreciated by the White American society and became an object of national pride, while the creators of the art-- the Black artists and people continued to be denied social, political and economic equality. Robeson was seen and loved by the people of dark humanity, especially people in India. The memory of his songs of struggle carried across generations who felt their souls stirred by Robeson the man and his voice. People participated in rallies and stood in protest of the imperialist and fascist American government’s attack on Robeson. They also celebrated Robeson despite the threats by the American government. But today this collective memory is dormant. It is dormant because the Indian people have been robbed off their revolutionary history and the organic connection with Black America because of the West-facing Indian intellectuals. The Indian freedom struggle produced artistic and literary expressions that reflected the strivings of the masses of Indian people and united us with the world humanity’s struggle for freedom from exploitation, famines, poverty and war. Together, we aspired for a world where we could determine our future and every human being had a right to reach their highest potential. We must revisit and remember the deep spiritual and cultural connection that we have with Black America. Instead of trying hard to assimilate into and seek acceptance from the White world, we must return to where we belong naturally- with all of darker humanity and its system of values. Neha is a graduate student at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign and a member of the Saturday Free School for Philosophy and Black Liberation.

Nandita Chaturvedi It was while living in the US and working with revolutionary scholar Dr. Anthony Monteiro that I first heard of Romesh Chandra. I was introduced to him as a revolutionary human being, told stories of how he would carry himself, how he spoke, and the spirit of the world communist movement he carried with him. These formed a deep impression on me as a young person who was still trying to find out the right ways to be and act in a complex and often hostile world. These stories made him real to me, a human being like myself who was compelled to take righteous and difficult actions by a moral calling. I and my comrades went on to research his life, we read his speeches and went to the archives. We began to refer to him as Romesh, as if he was one of us. It was through this research that I first learnt of Perin Chandra. She was mentioned in many of the writings we read and mentioned in passing by many people. People on the Indian left would talk of ‘Perin and Romesh Chandra’ as if they were two sides of the same person. We went on to meet Primla Loomba while visiting Delhi for a few months and she told us of how she was comrade in arms with Perin, they would spend days on end together, always engaged with intensity in political work and interacting with the Indian people. Yet, I did not fully grasp Perin’s life and the importance of her work. Recently, in a conversation with a trade unionist my colleague was explaining our plans to honor Romesh Chandra and Paul Robeson together. Upon hearing Romesh’s name, he stressed that we must put Perin alongside them. He went on to describe his work with her. At the end he said, ‘She was like a mother to me.’ We were compelled by this moving testimony to research her life more, and yet could find few resources in terms of books or articles. Perin Chandra is one of those self sacrificing revolutionaries produced by the Indian freedom struggle who lived completely and absolutely for the Indian people, and for humanity at large. She did not leave behind a memoir because she did not think it important to talk about herself. Yet, she remains alive among those who worked with her and knew her. Since that conversation I have spoken with many others who knew her, and each one of them has repeated the sentiment, she was like a mother to me. Few among the younger generations know that a Perin Chandra existed, and this limits their imaginary for what they see possible for their own lives. This article is an effort to document what the people around her remember of her so her life can be made available as pedagogy to the youth. Indian Freedom Movement Perin Bharucha was born on October 2, 1918, the year of the satyagraha struggle in Kheda, exactly 51 years after Gandhi’s birth. She was born in Chaman, Balochistan which now falls in Pakistan, the daughter of Phiroze Byramji Bharucha, an army doctor and later Surgeon General of Lahore. She became involved in India’s struggle for freedom during her student days in Lahore. She soon became a leader in the student movement in Lahore, organizing a strong cadre of young people to participate in relief efforts for the Bengal famine, and other activities of the freedom movement. After her graduation, she joined the Communist Party of India. In 1941 she was elected the first woman General Secretary of the All India Students Federation. Perin made a serious and stern student leader. In the year the Quit India movement was launched, 1942, she married her comrade Romesh Chandra. The two of them immersed themselves in political work of the party and the Quit India Movement in Lahore. Her closest associates in this time included Primla Loomba who would later lead the National Federation of Indian Women and with whom Perin also worked closely later. Also in 1942, Rameshwari Nehru was released from prison for her involvement in the Quit India campaign. Rameshwari was then head of the Punjab Women's Self-Defense League and she met with Perin to take over the organization of All India Women’s Council. Perin had collected a small group of young women with whom she worked among the poor to politically engage them and draw them into the struggle for freedom. Perin and Romesh’s lives were uprooted in the partition of India and they shifted to Bombay, and then to Delhi. After India’s independence, Perin joined the Patriot, a newspaper started by Aruna Asaf Ali. In the 1960s she left the Patriot to work in the peace movement. Beginnings of the Indian Peace Movement The All India Peace Council was founded in 1951 to respond to the need for championing peace following the destruction of the second world war, and to carry out the education of the people on the link between imperialism and war, and the importance of peace for a newly independent nation such as India which was struggling with crushing poverty, hunger and illiteracy. Its founding members included Congress freedom fighters Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew and Pandit Sundarlal, communist party leaders Ajoy Ghosh and A K Gopalan, revolutionary scholars such as D D Kosambi, and revolutionary artists like Prithviraj Kapoor, Balraj Sahni, Rajendra Singh Bedi, Vallathol, among others. Romesh Chandra became its general secretary in 1952 with Saifuddin Kitchlew as President and several vice presidents that included DD Kosambi and Mulk Raj Anand. On the other hand, the Afro-Asian People's Solidarity Organisation was founded in 1957 in Cairo to build solidarity with national liberation movements that were still struggling for freedom from colonial oppression across Africa and Asia and their promotion on the world stage. AAPSO aimed to mount an ideological defense of newly independent nations against world imperialism that was determined to prove that darker nations were not fit to rule themselves. The organization of AAPSO aimed to build on the legacy of the Bandung conference in 1955 to organize conferences attended by people from all the world and increase friendship and understanding between darker nations. It was organized in 1957 following two such conferences open to ordinary people held in New Delhi; the Conference of Asian Countries on the Relaxation of International Tension held in 1955 eleven days prior to the Bandung conference and attended by thousands of people, and the 1947 Inter Asian Relations Conference. In India, the aims and activities of these two organizations were so closely linked that they merged together to form the All India Peace and Solidarity Organization in 1972. AIPSO adopted the slogan ‘Peace is everybody’s business’. Perin Chandra assumed leadership of AIPSO in 1972 and remained its general secretary till 1991. AIPSO and the Struggle for India’s National Sovereignty and People’s Liberation Under her leadership, AIPSO engaged in work on broad issues that had to do with India’s sovereignty, the world peace and solidarity movement. AIPSO was a broad movement, and the very antithesis of sectarian politics. AIPSO was instrumental in organizing events and conferences in support of the people’s liberation struggle in Vietnam against American occupation, as well as the cause of the Palestinian people. It also played a huge role in Indian support for the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. AIPSO worked to inform the Indian people about the genocide in Bangladesh, the Bangladeshi liberation struggle and developing political support for it. They organized relief efforts for the refugees flooding into Bengal from East Pakistan. The threat of direct war with the US made stronger by the American government sending their navy’s 7th fleet to the Bay of Bengal in support of the Pakistani genocidal army made a deep impression on the Indian people. After the independence of Bangladesh, the WPC awarded Sheikh Mujibur Rehman the Joliot Curie Peace Prize in 1973. Romesh visited Bangladesh to confer the award on him, and stayed in Bangabandhu’s house. Perin’s consciousness was formed in the struggle against British imperialism and she was witness to the assault of American imperialism on African, Asian and Latin American liberation movements, including the assassination of leaders like Patrice Lumumba and Salvador Allende. She understood the workings of imperialism, and the American intelligence apparatus in particular. She did not underestimate the threat that American forces in India posed to the sovereign Indian state. It was in this context that she understood Indira Gandhi’s declaration of the emergency in 1975 in response to the Jayaprakash Narayan led movement to oust Indira Gandhi. She saw the importance of defending the Indian state, which was born out of a struggle that she herself had fought in. In this period Perin and AIPSO worked in tandem with the Indian state and Indira Gandhi’s government. In 1975, AIPSO organized the Patna conference against fascism. The Patna conference was a marvel of organization. It collected about 6,000 delegates from all over India. A vast tent city was set up with space for the sessions, exhibitions, kitchens etc. The city was named after the Indian minister Lalit Narayan Mishra, who had been assassinated in a suspected CIA supported plot the same year. Halls and gates in the city upheld the names of anti-imperialist fighters from all over the world -- Salvador Allende, Mujibur Rehman, Martin Luther King Jr, Patrice Lumumba and Amilcar Calbral among others. Leading up to the conference rallies and conferences were held in every corner of India against fascism, in which tens of millions of people participated. The Patna conference put forward important ideas to understanding the world and domestic situation at that time, and its contributions remain relevant today. The conference put forward a ‘Declaration of Solidarity with the Struggle of the Indian People Against Imperialism, Fascism and Reaction’ which extended the full solidarity of the conference to ‘democratic forces in India and to the Government of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’. They recognized the CIA’s efforts to sabotage democratic movements in the Indian subcontinent, most recently through the murder of Sheikh Mujibur Rehman. The American military had then been building a nuclear base in the Indian Ocean on Diego Garcia, which continues to be in American control today. Arms were being pumped at that time into Pakistan. Further, they saw fascism expressing itself in India through the coming together of ‘right extremists and Left adventurists’ under the slogan of ‘total revolution’. They saw the emergency as a blow to fascist conspiracy in India and a win for the struggle for democracy. The way the Patna conference saw the forces of fascism is in contrast to the way the term is used today. The Patna conference tied the struggle against fascism to the struggle against multinational corporations, feudal and monopoly interests, poverty and hunger. Fascism to them was linked to the action of forces aligned with world imperialism acting against a democratically elected government of the Indian people. They quoted Nehru to say that fascism and imperialism were twins. They saw the Indian state as an expression of the people’s democratic aspirations, and a bastion against fascism. Today, the labeling of a democratically elected Indian government as fascist by the Indian intelligentsia is in stark contrast to this. The role of imperialism in Indian politics today is underappreciated, and to determine the nature of the Indian state, we must understand the state’s relationship to Western imperialism. Another remarkable conference was held in Bhopal in 1985 to observe one year since the horrific Bhopal gas tragedy. The gas tragedy had claimed around 4000 lives in and around Bhopal when a lethal gas leak occurred from American company Union Carbide’s factory in December 1984. Over 500,000 people were exposed to the highly toxic gas, leading to highly disabling and long term injuries in some cases. Union Carbide refused to take complete responsibility for the leak, despite conclusive proof of negligent practices. Several cases linked to this still remain open in Indian and American courts. AIPSO took up the charge for this and the conference organized in 1985 addressed multinational corporations in India and their contempt for the Indian people. Perin also remained politically close to Indira Gandhi throughout her time in government. After the assassination of Indira Gandhi by operatives of the Khalistani movement, religious riots erupted in Delhi and Punjab. It was clear that this religious polarization was linked to Western and CIA support of the Khalistanis. In the years following this, Perin and AIPSO followed in Gandhi’s footsteps, working among the people to quell violence and mistrust. Massive peace rallies were held in Delhi in 1986 against religious extremism and for peace among the people. AIPSO served as a broad forum for discussion and airing of different subjects to do with the Indian people’s struggle for democracy. Under Perin’s leadership, it concerned itself not only with the struggle for international solidarity and peace, but any topic that had to do with Indian society’s struggle against poverty, illiteracy and foreign domination. This followed naturally from their ideological linking of peace with national sovereignty and self determination. The Conduct of a Revolutionary Perin worked closely with Aruna Asaf Ali and Primla Loomba in Delhi who were President and Vice President of the National Federation of Indian Women. In studying the lives of Indian women revolutionaries one realizes how closely integrated into the freedom struggle was the movement for women’s liberation in India. It is through this history, and the support of these revolutionary women for the leadership of the national movement, as well as the history of leadership in the national movement by revolutionary women, that we must view the attacks on Gandhi as a misogynist. Romesh Chandra was elected General Secretary of the World Peace Council in 1966 and spent the majority of his time traveling outside of India in connection with this work. In this time Primla Loomba and Perin would spend many days engaged in political work together from morning till evening. Like other revolutionaries, Perin formed deep and close bonds with her comrades based on shared commitments and the common trials of political life. She was loved deeply by those younger than her. She saw the development of younger cadres in the peace movement a central part of her work. She concerned herself with not only the political aspect of their lives, but also the personal. Dr. Sadashiva, who worked closely with her in the 1980s, told me that if he did not come to the AIPSO office for more than a few days she would personally drive over to his home to ask where he had been. She took responsibility for the younger people around her to train them to think not only politically, but to also deal with the trials of life. She viewed them as not only her cadre, but as the future of the nation. Ram Mohan Rai, who came up in the student movement when Perin was leading AIPSO, narrated to me how she embraced the youth. As young people interested in the Soviet Union, Ram Mohan Rai and his colleagues were trying to organize a youth conference on friendship between India and the Soviet Union and decided to start a youth society for this purpose. The older leadership of the Indo-Soviet Cultural Society (ISCUS) dismissed and discouraged them; they saw this endeavor as a competing organization to ISCUS. This of course was contrary to the spirit of solidarity movement, which has always attempted to engage and educate the youth on world affairs. It was Perin who lent her support to them at this time and made sure that a representative from the Soviet embassy attended the conference that was organized in Saharanpur. Perin strove to keep the culture of the peace movement broad and open, away from sectarianism and petty power politics. Ram Mohan Rai visited Tashkent in 1981 under Perin’s recommendation for a youth summit. The experience influenced and affected him greatly, as he met students and youth from all over the world. The people he met there would ask him about three Indian figures -- revolutionary film actor Raj Kapoor whose films were popular all over the world, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi who was then loved in the Soviet Union, and Romesh Chandra. They would be greatly impressed when he told them of how he had attended classes in Delhi both with Romesh and Perin Chandra. A Model for Us Perin Chandra’s life and her work in the peace movement deserves study. In a time when the youth of this country are starved for models that are worthy of them, she shines as an example of a life of purpose and sacrifice. Her name should be known among the people of India, for she represents the best of the tradition of the Indian freedom struggle. Among those who knew her, she is remembered dearly as a kind but firm teacher who taught equally through example and intellectual training. At this time, when India stands at the crossroads between the dying West and the multipolar world in the process of being birthed, we look to her for the direction we must take. How can we stand in solidarity with the oppressed peoples of the world and our own country? Can we imagine a different future where peace is not a distant dream but the norm upon which human creativity, art and science can prosper? Her life shows us that we must fulfill our destiny as a people, complete the project of the freedom struggle she worked so hard to build, and achieve our country. Thank you to Dr. Sadashiv and Ram Mohan Rai for sharing their experiences and understanding of their time in the peace movement for the purpose of this article.

Archishman Raju Paul Robeson was an artist, singer, philosopher, linguist and political revolutionary. To understand Paul Robeson as a figure, one must not confine him to any narrow aspect of his personality but attempt to understand the whole of his life. In 1935, Robeson had written, “The race which first learns to balance equally the intellectual and the emotional---to use the machines and couple them with life of true intuition and feeling such as the Easterns know--- will produce the supermen.” In some ways, he himself came to become the embodiment of such a superman, a man the likes of which the world has perhaps never seen since. He represented a new kind of human being, who heralded the emerging freedom of the darker peoples of the world.

It is no surprise then that Paul Robeson was a hero to the darker nations and peoples of the world. The names of the people who admired him include Jawaharlal Nehru, Krishna Menon, Indira Gandhi, Kwame Nkrumah, Oliver Tambo, Yusuf Dadoo, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Mme. Sun Yat Sen, Fidel Castro and many more. The U.S. Government confiscated Paul Robeson’s passport because it did not allow him to travel to the newly independent nations and expose the truth about U.S. society. They practically said as much. It is difficult to find an anti-colonial struggle at that time that Paul Robeson did not actively support and fight for. Paul Robeson was thus a figure who wielded immense moral and political authority in the darker world. Paul Robeson was an early supporter of the Indian struggle for independence. In 1942, as the whole Congress leadership was arrested following the Quit India movement, the Council on African Affairs, which he founded, held a Free India Rally in New York. Paul Robeson spoke at the rally and told the audience of his early friendship with Indian revolutionaries. Jawaharlal Nehru would later say “Paul Robeson is one of the greatest artists of our generation” Similarly, Robeson would support the Chinese Struggle against Imperialism. He became close friends with Liu Liangmo, a Chinese musician and collaborated with him to produce an album of songs, Chee Lai, Songs of New China. This was to become China’s national anthem. Soong Ching Ling, also known as Madame Sun Yat Sen, said Robeson is “the voice of the people of all lands”. Robeson was appointed honorary director of the China Defense League that she founded . Robeson had started the Council on African Affairs in 1937. The task of the Council was “to give concrete help to the struggle of the African masses” and “to smash the iron curtain of secrecy and double talk that surround the schemes for intensified imperialist exploitation of Africa and its people”. A young Kwame Nkrumah would participate in the formulation of the Council’s objectives. The Council held rallies to free Africa as well as worked to combat apartheid in South Africa. Oliver Tambo later called Robeson “a universal idol and a friend dear to all who know him”. Yusuf Dadoo would say Robeson had done “Pioneering work in mobilising World Public opinion against Racism and Colonialism and For Peace”. Robeson participated in a rally denouncing the American intervention in Korea in June, 1950 saying “we may be sure the people of Korea, Indo-China, the Philippenes and Formosa will not treat their invaders lightly any more”, just days before the order would come to confiscate his passport. He later would call Ho Chi Minh “the Toussaint L’Ouverture of Indo-China”. In some ways, the Bandung Conference was the coming together of these many struggles that Robeson had known and participated in. It is no wonder that he said “How I should have loved to be at Bandung!” As he said in his message “I have long had a deep and abiding interest in the cultural relations of Asia and Africa. Years ago I began my studies of African and Asian languages and learned about the rich and age-old culture of these mother continents of human civilization. The living evidence of the ancient kinship of Africa and Asia is seen in the language structures, in the arts and philosophies of the two continents. Increased exchange of such closely related cultures cannot help but bring into flower a richer, more vibrant voicing of the highest aspirations of colored peoples the world over” Indeed, in 1934, Robeson had declared “I want to be African”. He had articulated the challenge of understanding and realizing his relationship to the civilizations of Africa. He said the natural question that faces a young black person is “What of value has Africa to offer that the Western world cannot give me?” Similarly, he said a young Chinese at a University in England might say “What has the chaos of conflicting misgovernments and household gods and superstitions to offer me?” As Robeson said, what they were looking at was “broken remnants of what was in its day a mighty thing; something which perhaps has not been destroyed, but only driven underground, leaving ugly scars upon the earth’s surface to mark the place of its ultimate reappearance”. Robeson thus saw that these ancient civilizations had something to offer to the world, but their own members must be willing to conduct patient inquiry and regenerate them for modern times. He himself dedicated himself to such inquiries and made many discoveries that have not been fully explored yet. Robeson discovered that “African languages…had exactly the same basic structure as Chinese”. As he said, “both the Chinese and African people make extensive use of tone”. Robeson was also fascinated by the Russian language and considered the Soviet Union as closer to Asia than to the West. It is not appreciated that Robeson spoke 25 languages, if not more. Apart from African languages like Swahili, Zulu and Yoruba, he spoke Chinese and Russian. Robeson suggested the possibility of a comparative study of civilizations in Asia and Africa, which remains to be fully done to this day. However, this comparative study could not be left to academics but must be done by revolutionaries who seeked to discover the commonalities that bind India, China and Egypt. Robeson would often remark about the similarities between these civilizations that were not fully understood. It should be noted that Robeson considered civilization to be a creation of ordinary people and also their inheritance. Thus, he paid particular emphasis on music and folk songs, which he felt had a potential to unite working people around the world. It is here that Robeson’s relationship with Liu Liangmo and Bhupen Hazarika attains special significance. Bhupen Hazarika had worked on Bistirna Parore based on Robeson’s rendition of Old Man River. He was also very influenced by Robeson’s emphasis on the Negro Spirituals. Robeson felt that this study of civilizations had an essential meaning for his time. He argued that Western bourgeois mind had become overly abstract and intellectual. In doing so, it had lost the creative intuition that informs the best of art, the vitality that underpins the human soul. Robeson held the hope that it would be the darker nations of the world that would provide this vitality. His emphasis on creative intuition is familiar to students of Indian philosophy who recognize that this kind of intuition was considered a legitimate form of acquiring knowledge. In some ways, his philosophical analysis carries even more significance today. Western science, particularly physics, has veered off into abstraction that few can even understand. The advent of Artificial Intelligence has created a new debate on the meaning of human beings and human intelligence. Despite the best attempts of the Western ruling elite, they will fail at trying to resolve the fundamental question of what constitutes a human being without considering the darker nations. These nations in turn must contribute to the resolution. Finally, Paul Robeson linked the concept of peace with culture. The question of war and peace haunts us, and peace is the precondition for human advancement. All our efforts must go towards fighting for peace which sets the precondition for human development. On Robeson’s 60th birthday in 1958, there were celebrations held for him in India, China, Vietnam and several parts of Africa. This no doubt contributed to Robeson finally getting his passport back soon after. In 1962, Kwame Nkrumah invited him to come to Ghana and teach. It was an offer that Robeson was unfortunately unable to take up because of his health. Nevertheless he spent the last years in the black community in Philadelphia. We must consider Paul Robeson to be our teacher today for he has left us a rich legacy which will guide the continuing struggle of the darker nations to realize themselves fully. This year, celebrations are being held in India and the US to commemorate Paul Robeson's 125th birth anniversary. This statement clarifies why we must celebrate Paul Robeson and learn from his life in this time. More information of the celebrations, and about Paul Robeson's life can be found at www.robeson125th.org We celebrate Paul Robeson on his 125th birth anniversary as a man for our times. As the world transitions from the age of empire to the age of humanity, Robeson’s legacy teaches us how we must prepare for the world to come. In 2023, the world is at a crossroads. The darker nations are rising, and demand a new democratic world order. South Africa, China, Russia, Brazil, India, Argentina, Mexico, Mali, Central African Republic, and Saudi Arabia join together in their common interest after decades of imperialist destabilization and division. Western economies face high inflation, rising interest rates, and bank failures. Meanwhile, the Western elite push humanity towards nuclear disaster in Ukraine and threaten China. The American people confront the ruling class with a crisis of legitimacy. As Martin Luther King prophesied in his speech “A Time to Break Silence”, the people reject the elite consensus of racism, deindustrialization, and war. They cry out for a new economic and social system based on human dignity and peace. Paul Robeson shows us a way forward in these turbulent times. As a Black American, Robeson saw himself in the masses of Asia and Africa and the working people world over. Though the American government barred him from attending the Bandung Conference of 1955, he sent his unwavering support, declaring that the very fact of the convening of the Conference signified a historic turning point in all world affairs and a new vista of human advancement. He expressed the support of the working people of the West, who had a vested interest in the defeat of imperialism abroad, since it was inextricably tied to racism and exploitation at home. Paul Robeson believed in the connection of Africa and Asia unmediated by the West. He observed that Western civilization was exhausted because of its obsession with reason and intellect at the expense of intuition and feeling, and left it to the great cultures of the non Western world to create a new human being who could use scientific knowledge for the upliftment of human life. He saw, as Du Bois did, that “Science is a great and worthy mistress, but there is one greater and that is Humanity which science serves; one thing there is greater than knowledge and that is the Man who knows.” He observed the continuity of the great cultures of the East with the great cultures of Africa, developing in a belt extending into Russia. He recognized folk culture as the expression of the wisdom and humanity of the people reflecting their historical journey and experience. He foresaw that this art and culture could be the basis of a forward movement of all humanity towards peace and love. So committed was he to folk culture, that he learned, spoke, and sang at least 25 languages including Chinese, Russian, and Yoruba. As Robeson believed in the darker nations, so too did he believe in the working people of the world. He believed in their ability to come together in defiance of the white supremacist warmongers. He identified racism with the bluebloods of Princeton and in the halls of Congress rather than with the majority of Americans. He believed in the moral capacity of working people to follow the Black tradition into the struggle for peace. He encouraged all Americans to join his people in singing their song, “I’m going to lay down my sword and shield down by the riverside... I’m going to study war no more!” Paul Robeson believed in the reconstruction of the American economy on the basis of peace and justice. He rejected the war economy created by white supremacist elites with its inflation, unemployment, deindustrialization, exploitation and hunger. He embraced a peace economy, with a monetary system for the people rather than the financiers, full employment, dignity, and self-determination. He advocated that the nations of Africa and Asia had the right to choose their own economic system in accordance with the needs of their people and to advance their civilizations without fear of retaliation. He knew that Western civilization’s greed would be its undoing, and judgment day was near for the great white masters of the world. Robeson believed that the artist must choose a side and elect to fight for freedom or slavery. He took positions that were neither safe, nor politic, nor popular, but because his conscience said it was right. He lived his life with extraordinary courage and humility, even in the face of political persecution. The House Un-American Affairs Committee tried to destroy him. The government denied his passport and took away his means of work. His so-called friends and allies canceled him. The ruling class tried to turn him from the most celebrated Black man on the planet to a nonentity. Throughout it all, he remained unbowed and unbroken. He never apologized for his stances and welcomed every new stride toward freedom. Even as his government tried to cancel him, his people and the people of the world rallied around him and loved him even more. As Urdu poet Ali Sardar Jafri wrote, “Whether or not you are proud of your songs/Songs are proud that they are your art/Our lands lie far apart/ But not our hearts/Your garden lies just beyond mine”. As a new world order rises and the old crumbles, we celebrate Robeson as a figure for our times. Robeson teaches us to believe in the capacity of the working people to reject the warmongers and embrace humanity. He teaches us to practice love in the sense Martin Luther King practiced it, not as sentimental bosh, but as the unifying principle of life, and the key that unlocks the door which leads to the ultimate reality. We must sing Robeson’s Song of the Rivers, which speaks of the merging of the Nile, Ganga, Yangtse, Volga, and the Mississippi into “the mightiest river of all–the people’s will for peace and freedom now surging in floodtide throughout the world”. Paul Robeson was a philosopher artist. Here we republish four of his writings, 'An Artist Must Take Sides', 'Primitives', 'I Want to be African' and 'Songs of My People' to make available the breadth and depth of his thinking.  The Artist Must Take Sides Speech at rally sponsored by National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief in aid of the Spanish Refugee Children, Royal Albert Hall, London, June 24, 1937-Daily Worker, November 4, 1937 Friends. I am deeply happy to join with you in this appeal for the greatest cause which faces the world today. Like every true artist, I have longed to see my talent contributing in an unmistakably clear manner to the cause of humanity. I feel that tonight I am doing so. Every artist, every scientist, must decide NOW where he stands. He has no alternative. There is no standing above the conflict on Olympian heights. There are no impartial observers. Through the destruction-in certain countries of the greatest of man's literary heritages, through the propagation of false ideas of racial and national superiority, the artist, the scientist, the writer is challenged. The battlefront is everywhere. There is no sheltered rear. The challenge must be taken up. Time does not wait. The course of history can be changed, but not halted. Fascism fights to destroy the culture which society has created; created through pain and suffering, through desperate toil, but with unconquerable will and lofty vision. Progressive and democratic mankind fight not alone to save this prevent a war of unimaginable atrocity from engulfing the world. cultural heritage accumulated through the ages, but also fight today to prevent a war of unimaginable atrocity from engulfing the world. What matters a man’s vocation or profession? Fascism is no respecter of persons. It makes no distinction between combatants and noncombatants. The blood-soaked streets of Guernica, that beautiful peaceful village nested in the Basque hills, are proof of that as are the concentration camps full of scientists and artists which in some western lands dot the countryside, bringing back the dark ages. The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative. The history of the capitalist era is characterized by the degradation of my people: despoiled of their lands, their culture destroyed, they are in every country, save one, denied equal protection of the law, and deprived of their rightful place in the respect of their fellows. Not through blind faith or coercion, but conscious of my course, I take my place with you. I stand with you in unalterable support of the Government of Spain, duly and regularly chosen by its lawful sons and daughters. Again I say, the true artist cannot hold himself aloof. The legacy of culture from our predecessors is in danger. It is the foundation upon which we build a still more lofty edifice. It belongs not only to us, not only to the present generation–it belongs to posterity--and must be defended to the death. May you rally every artist, every scientist, every writer in England who loves democracy. May you rally to the side of Republican Spain every black man in the British Empire. May your inspiring message reach every man, woman, and child who stands for freedom and justice. For the liberation of Spain from the oppression of fascist reactionaries is not a private matter of the Spaniards, but the common cause of all advanced and progressive humanity.

Songs of My People

Sovietskaia muzyka (Soviet Music), No. 7, July 1949, pp. 100–104 Translated from the Russian by Paul A. Russo There is an old Spanish proverb that goes: sing me your folk songs and I'll tell you about the character, customs, and history of your people. How true! Folk songs are, in fact, a poetic expression of a people's innermost nature, of the distinctive and multifaceted conditions of its life and culture, of the sublime wisdom that reflects that people's great historical journey and experience. This is as true of the very rich treasury of songs of the Russian and Ukrainian peoples, as it is of the wonderful songs of the Spanish, French, Czech, Italian, Polish, Chinese, Norwegian, Georgian, Armenian, and many other peoples of the world. This is utterly and completely true for the song culture of my people. I don't think I have to go into a detailed appraisal here of the great artistic merit of Negro folk music or of its unquestionable significance for all mankind. This is universally acknowledged. Even in capitalist America, where there exists racial discrimination of revolting proportions, where many "cultured" whites refuse to recognize the Negro as a human being—even there our folk songs constitute, as strange as it may seem, an object of national pride for many Americans. I am well aware that you in the Soviet Union, as nowhere else in the world, know how to honor and appreciate every artistic manifestation of a people's spirit, every genuine national art. I know, too, that Soviet audiences love and esteem the Negro people's songs, with which they have become familiar through the performances of such outstanding artists as Roland Hayes and Marian Anderson. I felt the full force of this passionate interest in and love of our folk songs during my own appearances in Moscow and Stalingrad. All the same, I also know that Soviet audiences are insufficiently acquainted with the history of Negro music and do not, perhaps, have a completely clear idea of the origins, sources, and the real content of Negro lyrics. This is all the more probable in that our official American musicology and music criticism have done everything to distort the Negro historical truth, to conceal the real social roots of Negro art, and to depict Negro culture as imitative, as permeated by the spirit of Christian meekness and slavish submissiveness to fate. This is why I should like to tell Soviet readers the truth about the songs created by the American Negroes, songs which bear the poetic impress of many facets of folk life, of the very nature and soul of the people, of its dreams and aspirations, of its long, hard struggle for the right to life, liberty, and independence. The music of the American Negro has its origins in the ancient culture of Africa. American Negroes are the direct descendants of various African tribes which–from the beginning of the seventeenth century–-English, Dutch, Spanish, and French merchant-plunderers began transporting en masse for sale to America. Torn from their native land and national culture, thrust into the most difficult conditions of slave existence amidst an alien and hostile population, the Negroes had to adapt themselves to an alien life, language, culture, and religion. The Christian religion, imposed by force, was one of the powerful weapons for the spiritual enslavement of the Negroes. Faith in the afterlife where all earthly sufferings would be compensated with heavenly bliss, and the preaching of meekness and submissiveness-these were the basic religious tenets which helped the white exploiters to keep in harness the mass of Negro slaves who were subjected to the most brutal treatment in their backbreaking labor for their masters. And yet this enslaved people, oppressed by the double yoke of cruel exploitation and racial discrimination, gave birth to splendid, inspired, life-affirming songs. These songs reflected a spiritual force, a people's faith in itself and a faith in its great calling; they reflected the wrath and protest against the enslavers and the aspiration to freedom and happiness. These songs are striking in the noble beauty of their melodies, in the expressiveness and resourcefulness of their intonations, in the startling variety of their rhythms, in the sonority of their harmonies, and in the unusual distinctiveness and poetical nature of their forms. In trying to explain this "miracle," some American musicologists are ready to ascribe the phenomenon of Negro Spirituals to the influence of English church music, Puritan psalms, etc. The unscientific nature and falsity of such explanations are easily demonstrated by pointing out that the white population among which the mass of Negroes has lived in the American South has never–not in the past, not at present–had a musical culture of song (including church singing) that is in the slightest way comparable in artistic merit to the Negro Spirituals. The so-called psalmody, that is, the Christian hymns which the Negroes could hear in church, represents primitive choral singing in a slow, strictly measured tempo with traditional cadences. Could this sanctimonious music really be the model for inspired folk singers? It would be wrong, of course, to deny the influence of church psalms or that of the folk songs of the immigrant population of America (the Scots, the Irish, the Spanish) on the development of Negro folk music. There were such influences. But they did not determine the distinctiveness and universal significance of the folk-song culture of the American Negroes. The power and beauty of Negro songs, the indigenous features that distinguish Negro folklore from culture, from the songs of all other peoples in the world, stem from ancient African songs, from the remarkable musicality which the Negroes inherited from their African ancestors. First of all, the idea has to be repudiated that African Negores were “savages”, people without culture. Many African peoples possessed their own distinctive and significant artistic culture long before the arrival of the European conquerors. They created their own language, distinguished-like Chinese-by the great precision and subtlety of intonational structure. They created a rich oral folklore, a distinctive decorative art (especially sculpture), and, finally, they possessed a highly developed and original musical art, distinguished by an extraordinary wealth of rhythm. Rhythm, the most intricate polyrhythmic constructions on the invariable and uniform pulsation of a basic, clear-cut meter–this is the basis of the musical speech of African Negroes. This basis has been fully preserved in the music of their American descendants. This characteristic syncopation, with all its rhythmic freedom and infinite variety, not only underwent its own development in Negro musical folklore, but also had a quite noticeable effect on the music of those peoples of North and South America among whom the Negroes lived. It is enough to become familiar with the folk music of Cuba, where Negro rhythms blend with elements of Spanish music; with the folk music of Brazil, which is based on Portuguese folk-song traditions fused with Negro influences; with the music of Haiti, which combines French and Negro features; and so on. I don't have to talk about the immense influence which Negro folk music has had on the development of the musical culture of the peoples of the USA. A particularly brilliant instance of this is seen in the works of the popular American composer of the middle of the last century, Stephen Foster, in whose numerous songs characteristic features of Negro music are distinctly perceptible. In still later times, these influences show up in full force in jazz. Rhythm is not the only feature which Negro music inherited from Africa. American Negro songs are close to African songs in the structure of their intonational harmony, in the improvising nature of their performing style, and in their form. But, of course, Spirituals are melodically far above their African forerunners. The American Negroes' sense of harmony is also highly developed. Let me relate here a story told by the well-known American historian of Afro-American music, Natalie Curtis-Burlin (Negro Folk Songs, Book III), about a certain German musician who visited Hampton Institute in Virginia and heard the singing of an immense chorus of Negro students. “Who worked with the chorus? This is remarkable!” exclaimed the musician. N. Curtis-Burlin's reply that no one had ever worked with the chorus did not satisfy him. "I mean," insisted the musician, "not who trained their voices (I understand, of course, that they sing without benefit of voice school), but who taught them the choral parts, who got them ready as a choral ensemble?"-No one. As N. Curtis-Burlin further relates, the nine hundred Negro boys and girls whose singing so impressed the German musician were not arranged and distributed by voice as in the usual chorus. The boys sat in a group on one side, the girls on the other. Each sang the part most comfortable for him within his normal range, free harmonizing the melody then and there during the singing. A first alto might turn up between two sopranos. A boy singing countertenor might be sitting next to a bass… "But the amazing, inspired singing of this immense chorus sounds utterly faultless in intonation; there is not the slightest deviation from tonality, and all without any accompaniment. " In fact, American Negroes have a remarkably developed flair for harmony. There is even a saying that aptly reflects this innate harmonic gift of the Negro people: "Put together the first four Negro fellows that come along and you've got a quartet." This tendency to harmonize melodies, such a natural phenomenon among the people, found its fullest expression in the performances of Spirituals (spiritual hymns), as well as in the performance of work songs (the so-called Plantation Songs), the performances of these usually being choral ones. The wealth and diversity of the melodic language of Negro songs is startling. A few examples here will suffice to show how freely and flexibly the melodic line moves, how expressive and noble is its outline, and how multifarious are the rhythmic-harmonic structures and forms of these folk songs. Here is one of the most splendid songs of my people: "Go Down Moses," a magnificent hymn, calling the people to the struggle for freedom. Go down, Moses, 'way down in Egypt land, Tell ole Pharoah, To let my people go. When Israel was in Egypt's land, Oppressed so hard they could not stand. . . etc. The forms of this song as in many other Spirituals are connected with religion. It would be a complete mistake, however, to conclude from this that the origins and content of these songs are purely religious. As I have already said, the Christian religion, propagated among the Negroes by force, was one of the strongest weapons for the spiritual enslavement of the people. The only book which the Negroes knew before the Civil-War period and the abolition of slavery (1863) was the Bible. Oppressed and persecuted, subjected to the curelest exploitation, the Negro people was very susceptible to the consolations promised by the Church. The Negroes sought in the Bible stories analogies with the history of their own slave existence, and drew from these stories faith in the coming retribution for their oppressors, faith in the triumph of truth and justice. The real content of the Spirituals in the overwhelming majority of cases was far removed from religious concepts. These were folk hymns, the poetical embodiment of the sufferings and struggle of an entire people, of its philosophy of life and its character, of its hopes and aspirations. The Spirituals reflected all the manifestations of the Negro people's social life. Therefore, the song "Go Down Moses," far from being a religious hymn, is rather an impassioned call to the struggle for the liberation of the Negro people. Moses, and the pharoahs, and the Jewish people are all merely poetic symbols which inspired the unknown singer who created this amazing song. Similarly, there is little that is religious in the song "Heab'n": I got a robe, you got a robe, All of God's children got a robe. When I get to heab'n goin' to put on my robe, Goin' to shout all over God's Heab'n. Ev'rybody talkin' about heab'n ain't goin' there, Goin' to shout all over God's heab'n. According to the testimony of the greatest Negro historian of the nineteenth century, Frederick Douglass, the heaven mentioned in this song is the North, the northern states of America where the Negroes, in contrast to the southern states, were not in bondage. In the minds of the benighted and downtrodden slaves of Alabama, Virginia, Florida, and Georgia, the northern states constituted that promised land for which the Negro population of the South yearned heart and soul. It seems to me that the same explanation fully reveals the real content of the song "Nobody Knows de Trouble I See": Oh, nobody knows de trouble I see, Nobody knows my sorrow... If you get there before me Tell them I'm comin'. With respect to genre, Negro musical folklore is very diversified. Along with a vast quantity of spiritual hymns, the American Negroes created a multitude of work songs, songs of lyrical content (the Blues), and dance tunes. Finally, recent investigations have for the first time revealed a whole new field of Negro songs–songs of protest, songs directly calling the Negroes to the struggle for their rights, and against lynch-law, against their exploiters, against capitalists. The work songs, as well as the songs of protest, are the fruit of collective creation. Their rhythm is born out of the work process. It may be the measured beat of the crowbar or pickaxe at excavation sites. It may be the synchronized movement of dockworkers loading barges. It may be the hard, monotonous work of the cotton pickers. These songs usually begin with an introduction by the leader that defines the rhythm of the work, and then the chorus joins in. Here is one model for such songs, “Cott’n Pickin’ Song,” created by the Negro cotton pickers of Florida: Chorus: This cott'n want a pickin' So bad! This cott'n want a pickin', So bad! Goin' clean all over this farm. Leader: When boss sold that cott'n, I ask for my half. He told me I chopped out My half with the grass. In the song there is a regular alternation between the refrain of the entire chorus and the recitative improvisations of the leader. The content of these improvisations, connected with the life of the given group of workers, at times is permeated by a venomous irony directed at the white bosses, at times has the character of a direct protest. A good example of a work song is the one I performed, "Water-Boy"; it, too, is built on the alternation between a free, recitative solo and a rhythmic, precise choral refrain. A special place in the corpus of Negro songs is occupied by songs of protest, which were first collected in the southern states in the nineteen-twenties by the American journalist, L. Gellert. These songs manifest in full measure the Negro workers' heroic revolutionary spirit, their hatred of their exploiters, and their yearning for the struggle for their human rights and freedom. The hard, exhausting work with a pickaxe or shovel in hand defines the rhythm and character of the melody. The example below gives a clear idea of the content of these songs: Sistren an' brethen, stop foolin' wid pray. When Black face is lifted, Lord turnin' away. Heart filled wid sadness, head bowed down wid woe, In his hour of trouble, where's a black man to go? We's buryin' a brudder, dey kill fo' de crime Tryin' to keep what was his all de time. When we's tucked him on under, what you goin' to do? Wait till it come dey's arousin' fo' you? Yo' head tain' no apple fo' danglin' from a tree Yo' body no carcass for barbacuin' on a spree. Stand on yo' feet, club gripped 'tween yo' hands, Spill dere blood too, show 'em yo's is a man's. While Spirituals, work songs, and songs of protest are collective creations and are performed collectively among the people, the blues (that is, lyrical songs, most frequently about love) express the emotional state of the individual. In the blues you frequently hear complaints about the evil fate of separation, about one's surroundings, about the hard and dangerous existence of a lonely creature in a faraway and alien big city. In contrast to Spirituals, many blues have authors. A popular Negro composer, for example, is William Handy, the author of many famous blues, including "Saint Louis Blues," "Florida Blues," "Memphis Blues," etc. The blues played a big role in the development of jazz and became the basis for contemporary dance (foxtrot, blues, tango). However, this is the topic for a special article and I cannot treat it in detail here. Let me just say that under capitalist conditions, where all forms and expressions of American art must subordinate themselves to the demands of the market, our native Negro music has been subjected to the very worst exploitation. Commercial jazz has prostituted and ruthlessly perverted many splendid models of Negro folk music and has corrupted and debased many talented Negro musicians In order to satisfy the desires of capitalist society. But, all the same, our splendid songs have survived and shall survive, enriching the real culture of America, providing my country's Composers with an inexhaustible supply of material for their creative work. Recent decades have seen the emergence of a series of talented Negro composers who have devoted their creative energies to the cultivation of the incalculable riches of our musical folklore. I list here such names as Samuel Coleridge Taylor, Henry Burleigh, Nathaniel Dett, William Dawson, William Grant-Still, Duke Ellington. These composers, each in his own way, have tried to find the way to creating a national Negro symphonic, oratorical, and operatic music. But these are so far just the first steps. We are still awaiting our Glinka who on the basis of Negro folk music will create a great, universally significant art, who will lay the foundation for a national school of composers. Meanwhile our serious composers find themselves in very difficult circumstances. Creatively and organizationally they are not united. Their material existence is far from secure. We are just now making attempts to unite Negro artists, performing artists, and musicians. For this purpose a progressive organization has been created in New York-"The Committee of Negroes in the Arts." Our dream is to establish creative contact with persons active in the Soviet Arts. We want to learn from your remarkable experience of building up a socialist culture; we want our art to be just as progressive and purposeful, just as national in spirit as the great art of the great Soviet people. |

CategoriesArchives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed