|

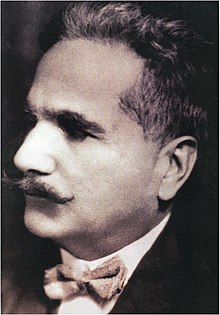

By Muhammad Iqbal This is the second preface to Asrar E Khudi written for the English translation of the poem in 1920. ‘That experience should take place in finite centres and should wear the form of finite this-ness is in the end inexplicable’ These are the world of Prof. Bradley. But starting with these inexplicable centres of experience, he ends in a unity which he calls Absolute and in which the finite centres lose their finiteness and distinctness. According to him, therefore, the finite centre is only an appearance. The test of reality, in his opinion, is all-inclusiveness; and since all finiteness is ‘infected with relativity,’ it follows that the latter is a mere illusion. To my mind, this inexplicable finite centre of experience is the fundamental fact of the universe. All life is individual; there is no such thing as universal life. God himself is an individual: He is the most unique individual. The universe, as Dr. McTaggart says, is an association of individuals; but we must add that the orderliness and adjustment which we find in this association is not eternally achieved and complete in itself. It is the result of instinctive or conscious effort. We are gradually travelling from chaos to cosmos and are helpers in this achievement. Nor are the members of the association fixed; new members are ever coming to birth to co-operate in the great task. Thus the universe is not a completed act: it is still in the course of formation. There can be no complete truth about the universe, for the universe has not yet become ‘whole’. The process of creation is still going on, and man too takes his share in it, inasmuch as he helps to bring order into at least a portion of the chaos. The Koran indicates the possibility of other creators than God.

Obviously, this view of man and the universe is opposed to that of the English Neo-Hegelians as well as to all forms of pantheistic Sufism which regard absorption in a universal life or soul as the final aim and salvation of man. The moral and religious ideal of man is not self-negation but self affirmation, and he attains to this ideal by becoming more and more individual, more and more unique. The Prophet said ‘Takkhallaqu bi-akhlaq Allah,’ ‘Create in yourselves the attributes of God.’ Thus man becomes unique by becoming more and more like the most unique Individual. What then is life? It is individual: its highest form, so far, is the Ego (Khudi) in which the individual becomes a self-contained exclusive centre. Physically as well as spiritually man is a self-contained centre, but he is not yet a complete individual. The greater his distance from God, the less his individuality. He who comes nearest to God is the completest person. Not that he is finally absorbed in God. On the contrary, he absorbs God into himself. The true person not only absorbs the world of matter; by mastering it he absorbs God Himself into his Ego. Life is a forward assimilative movement. It removes all obstructions in its march by assimilating them. Its essence is the continual creation of desires and ideals, and for the purpose of its preservation and expansion it has invented or developed out of itself certain instruments, e.g. senses, intellect, etc., which help it to assimilate obstructions. The greatest obstacle in the way of life is matter, Nature; yet Nature is not evil, since it enables the inner powers of life to unfold themselves. The Ego attains to freedom by the removal of all obstructions in its way. It is party free, partly determined, and reaches fuller freedom by approaching the Individual who is most free---God. In one world, life is an endeavour for freedom. The Ego and the Continuation of Personality In man the centre of life becomes an Ego or Person. Personality is a state of tension and can continue only if that state is maintained. If the state of tension is not maintained, relaxation will ensue. Since personality, or the state of tension, is the most valuable achievement of man, he should see that he does not revert to a state of relaxation. That which tends to maintain the state of tension tends to make us immortal. Thus the idea of personality gives us a standard of value: it settles the problem of good and evil. That which fortifies personality is good, that which weakens it is bad. Art, religion, and ethics must be judged from the standpoint of personality. My criticism of Plato is directed against those philosophical systems which hold up death rather than life as their ideal---systems which ignore the greatest obstruction to life, namely, matter, and teach us to run away from it instead of absorbing it. As in connection with the question of the freedom of the Ego we have to face the problem of matter, similarly in connection with its immortality we have to face the problem of time. Bergson has taught us that time is not an infinite line (in the spatial sense of the word ‘line’) through which we must pass whether we wish it or not. This idea of time is adulterated. Pure time has no length. Personal immortality is an aspiration: you can have it if you make an effort to achieve it. It depends on our adopting in this life modes of thought and activity which tend to maintain the state of tension. Buddhism, Persian Sufism and allied forms of ethics will not serve our purpose. But they are not wholly useless, because after periods of great activity we need opiates, narcotics, for some time. These forms of thought and action are like nights in the days of life. Thus, if our activity is directed towards the maintenance of a state of tension, the shock of death is not likely to affect it. After death there may be an interval of relaxation, as the Koran speaks of a barzakh, or intermediate state, which lasts until the Day of Resurrection. Only those Egos will survive this state of relaxation who have taken good care during the present life. Although life abhors repetition in its evolution, yet on Bergson’s principle the resurrection of the body too, as Wildon Carr says, is quite possible. By breaking up time into moments we spatialise it and then find difficulty in getting over it. The true nature of time is reached when we look into our deeper self. Real time is life itself, which can preserve itself by maintaining that particular state of tension (personality) which it has so far achieved. We are subject to time so long as we look upon time as something spatial. Spatialised time is a fetter which life has forged for itself in order to assimilate the present environment. In reality we are timeless, and it is possible to realise our timelessness even in this life. This revelation, however, can be momentary only. The Education of the Ego The Ego is fortified by love (ishq). This word is used in a very wide sense and means the desire to assimilate, to absorb. Its highest form is the creation of values and ideals and the endeavour to realise them. Love individualises the lover as well as the beloved. The effort to realise the most unique individuality individualises the seeker and implies the individuality of the sought, for nothing else would satisfy the nature of the seeker. As love fortifies the Ego, asking (su’al) weakens it. All that is achieved without personal effort comes under su’al. The son of a rich man who inherits his father’s wealth is an ‘asker’ (beggar); so is every one who thinks the thoughts of others. Thus, in order to fortify the Ego we should cultivate love, i.e. the power of assimilative action, and avoid all forms of ‘asking,’ i.e. inaction. The lesson of assimilative action is given by the life of the Prophet, at least to a Mohammedan. In another part of the poem I have hinted at the general principles of Moslem ethics and have tried to reveal their meaning in connection with the idea of personality. The Ego in its movement towards uniqueness has to pass through three stages:

This (divine vicegerency, niyabat-i-ilahi is the third and last stage of human development on earth. The naib (vicegerent) is the vicegerent of God on earth. He is the completest Ego, the goal of humanity, the acme of life both in mind and body; in him the discord of our mental life becomes a harmony. The highest power is united in him with the highest knowledge. In his life, thought and action, instinct and reason, become one. He is the last fruit of the tree of humanity, and all the trials of a painful evolution are justified because he is to come at the end. He is the real ruler of mankind; his kingdom is the kingdom of God on earth. Out of the richness of his nature he lavishes the wealth of life on others, and brings them nearer and nearer to himself. The more we advance in evolution, the nearer we get to him. In approaching him we are raising ourselves in the scale of life. The development of humanity both in mind and body is a condition precedent to his birth. For the present he is a mere ideal; but the evolution of humanity is tending towards the production of an ideal race of more or less unique individuals who will become his fitting parents. Thus, the Kingdom of God on earth means the democracy of more or less unique individuals, presided over by the most unique individual possible on this earth. Nietzsche had a glimpse of this ideal race, but his atheism and aristocratic prejudices marred his whole conception.

0 Comments

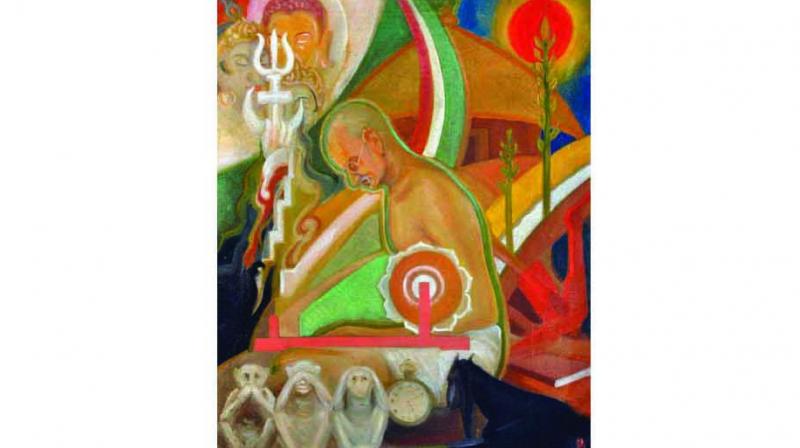

By Bal Gangadhar Tilak We are republishing an essay written by Tilak on his book Gita Rahasya and the reasons he wrote it.  Gandhian Philosophy (1946) by Upendra Maharathi Gandhian Philosophy (1946) by Upendra Maharathi Let me begin by telling you what induced me to take up the study of Bhagavad Gita. When I was quite a boy, I was often told by my elders that strictly religious and really philosophic life was incompatible with the hum-drum life of every day. If one was ambitious enough to try to attain Moksha, the highest goal a person could attain, then he must divest himself of all earthly desires and renounce this world. One could not serve two masters, the world and God. I understood this to mean that if one would lead a life which was the life worth living, according to the religion in which I was born, then the sooner the world was given up the better. This set me thinking. The question that I formulated for myself to be solved was: Does my religion want me to give up this world and renounce it before I attempt to, or in order to be able to, attain the perfection of manhood? In my boyhood I was also told that Bhagavad Gita was universally acknowledged to be a book containing all the principles and philosophy of the Hindu religion, and I thought if this be so I should find an answer in this book to my query; and thus began my study of the Bhagavad Gita. I approached the book with a mind prepossessed by no previous ideas about any philosophy, and had no theory of my own for which I sought any support in the Gita. A person whose mind is prepossessed by certain ideas reads the book with a prejudiced mind, for instance, when a Christian reads it he does not want to know what the Gita says but wants to find out if there are any principles in the Gita which he has already met within Bible, and if so the conclusion he rushes to is that the Gita was copied from the Bible. I have dealt with this topic in my book Gita Rahasya and I need hardly say much about it here, but what I want to emphasize is this, that when you want to read and understand a book, especially a great work like the Gita---you must approach it with an unprejudiced and unprepossessed mind. To do this, I know, is one of the most difficult things. Those who profess to do it may have a lurking thought or prejudice in their minds which vitiates the reading of the book to some extent. However I am describing to you the frame of mind one must get into if one wants to get at the truth and however difficult it be, it has to be done. The next thing one has to do is to take into consideration the time and the circumstances in which the book was written and the purpose for which the book was written. In short the book must not be read devoid of its context. This is especially true about a book like Bhagavad Gita. Various commentators have put as many interpretations on the book, and surely the writer or composer could not have written or composed the book for so many interpretations being put on it. He must have but one meaning and one purpose running through the book, and that I have tried to find out. I believe I have succeeded in it, because having no theory of mine for which I sought any support from the book so universally respected, I had no reason to twist the text to suit my theory. There has not been a commentator of the Gita who did not advocate a pet theory of his own and has not tried to support the same by showing that the Bhagavad Gita lent him support. The conclusion I have come to is that the Gita advocates the performance of action in this world even after the actor has achieved the highest union with the Supreme Deity by Gnana (knowledge) or Bhakti (Devotion). This action must be done to keep the world going by the right path of evolution which the Creator has destined the world to follow. In order that the action may not bind the actor it must be done with the aim of helping his purpose, and without any attachment to the coming result. This I hold is the lesson of the Gita. Gnanayoga there is, yes. Bhaktiyoga there is, yes. Who says not? But they are both subservient to the Karmayoga preached in the Gita. If the Gita was preached to desponding Arjuna to make him ready for the fight--for the action--how can it be said that the ultimate lesson of the great book is Bhakti or Gnana alone? In fact there is blending of all these Yogas in the Gita and as the air is not Oxygen or Hydrogen or any other gas alone but a composition of all these in a certain proportion so in the Gita all these Yogas are blended into one. I differ from almost all the commentators when I say that the Gita enjoins action even after the perfection in Gnana and Bhakti is attained and the Deity is reached through these mediums. Now there is a fundamental unity underlying the Logos (Ishwara), man, and world. The world is in existence because the Logos has willed it so. It is His Will that holds it together. Man strives to gain union with God; and when this union is achieved the individual Will merges in the mighty Universal Will. When this is achieved will the individual say: “I shall do no action, and I shall not help the world”---the world which is because the Will with which he has sought union has willed it to be so? It does not stand to reason. It is not I who say so; the Gita says so. Shri Krishna himself says that there is nothing in all the three worlds that He need acquire, and still he acts. He acts because if He did not, the world’s Will will be ruined. If man seeks unity with the deity, he must necessarily seek unity with the interests of the world also, and work for it. If he does not, then the unity is not perfect, because there is union between two elements out of the 3 (man and Deity) and the third (the world) is left out. I have thus solved the question for myself and I hold that serving the world, and thus serving his Will, is the surest way of Salvation, and this way can be followed by remaining in the world, and not going away from it. Sambarta Chatterjee I have always been drawn to the idea that our inner worlds, our selves, are not a thing apart from our outer lives: we derive a sense of purpose and meaning from our inner world, a meaning that is necessary to navigate the world and which informs the lives we lead. I felt that in order to live a meaningful life, our inner world must be known and studied, and this knowledge is self-contained. Ultimately, noone could know me better than myself, and this knowledge could only come from delving inwards. I was fascinated by philosophical musings on the meaning of life and the connections and contradictions between the inner and outer life, and in searching for a framework quickly came across the 20th century European existentialists. I was heavily impressed by them. I shared in their ‘discovery’ of the fact that the essence of man, the search for meaning, lay in contradiction to the reality of our outer, ‘existential’ nature. My idea of who I wanted to be always seemed to clash with who I really was. The existential question of how to bridge that gap was a serious question, and I tried to go where Camus or Sartre would take me. The impression that existentialism bore upon me was that this journey was definitely an individual one. I was convinced that these questions were the purview of a small minority of people, who were necessarily isolated from their surrounding world and the majority of humanity. It seemed a logical conclusion that our place, and role, in the outer, objectively real world, could help little in answering the questions I was struggling with. This idea seemed strangely comforting, since it freed me from the responsibility of making myself understood to the world around me. This comfort was nevertheless sustained by the fact that there were others, even if few, who shared this conviction.

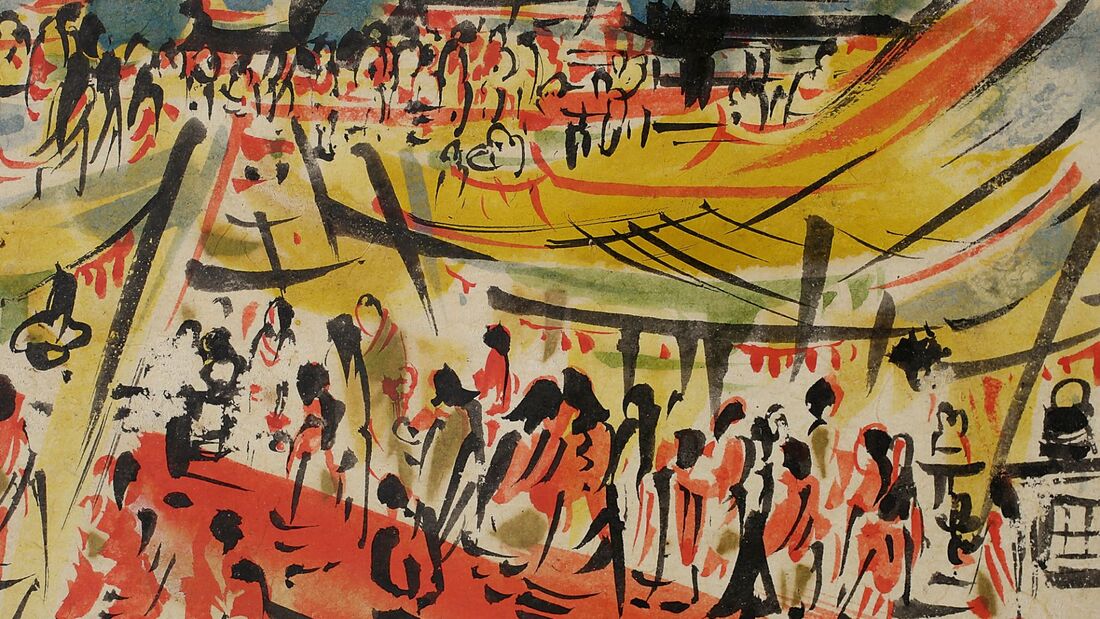

But did I truly hold this conviction? I found myself increasingly incapable of isolating myself from the world, from those who lived ordinary and beautiful lives, different from my own. I couldn’t convince myself that my lifeworld was fundamentally different from ordinary people, poor and struggling, like the young boy who accompanied his janitor father in garbage collection in my neighborhood under the most immiserating (and seemingly permanent) conditions. I was told by Sartre that “existence precedes essence”, but I saw that that boy had aspirations not very different from mine, in spite of his existential conditions, and knew that poor people everywhere strove for both bread and beauty. Was I truly convinced that “the one truly serious philosophical problem is that of suicide”, as Camus would have us believe? What of poverty and suffering? What of love and struggle? If existential anguish was irreducible, what was the way forward? Camus’ answer of embracing the absurd gave me absolutely nothing, for there was nothing remotely absurd about poverty or love, nor in the struggle to rise above degradation which characterized the lives of millions. The earlier comfort that came with an adolescent indifference to the world, seemed to be waning. I sensed that my notions about philosophy were at odds with the life I wanted to lead, to participate and be involved in the lifeworld of people. What then was the purpose of philosophy? Were questions of the inner world, a sense of self, after all futile? And yet I knew I did have an inner world which had to be understood, which was not irrelevant to the outer world of degradation and aspirations. In searching for a philosophical framework that can accommodate the whole reality of the world I see, I had to look toward the traditions that produced me and the others of my generation: the anticolonial and antiracist freedom movements of the 20th century. Muhammad Iqbal is a towering figure rooted in this tradition. His ideas serve to illuminate the dark alleys that existentialism may lead us to, and his revolutionary answers to questions of the inner world can transform us and lead us to light. Fortification of the self – to what end ? Iqbal wrote Asrar-e-Khudi (‘Secrets of the Self’) in 1915, speaking to a subject people of a nation yet to be, whose sense of themselves was being perpetually distorted by a colonial system that controlled every aspect of their lives. What passed for education was a series of racist policies designed to indoctrinate the intellectual class into participating in their own subjugation and breed a sense of inferiority and desolation among the masses. The inner world of an oppressed people seemed all but irrelevant to the outer reality of colonialism, and yet Iqbal urged to delve inward and strengthen a sense of self. “Tho’ I am but a mote, the radiant sun is mine: Within my bosom are a hundred dawns. My dust is brighter than Jamshid’s cup It knows things that are yet unborn in the world.”' To the most downtrodden and disinherited, Iqbal’s words are a reminder of their true power and agency. The disinherited knows the rightful place of man in the world, which is yet to be manifested in reality. The human condition, the contradiction between our sense of self and our outer existential condition is most profound in the oppressed. And Iqbal offers a way out, from the inner desolation and outer devastation by radically reintroducing the meaning of Life itself. “Life is preserved by purpose: Because of the goal its caravan-bell tinkles. Life is latent in seeking, Its origin is hidden in desire. Keep desire alive in thy heart, Lest thy little dust become a tomb.” The purpose of life is “the creation of values and ideals and the endeavor to realize them”, the ends for which one must strengthen the self by recognizing its true potential. The search for meaning and the struggle to become ourselves is inseparably tied to “desire” or ideals, a sense of morality. The sense of morality is at once internal and external. It pertains to the outer world and our participation in it, but we are active participants in its creation. The inner world of the individual is therefore not only a part of, but is capable of making a contribution to and shaping the objective outer world. The price of the contribution is the recognition of our incompleteness, the chasm between our desire-image and who we really are. And the movement of life, for the individual and for humanity, is to overcome this incompleteness, by bringing about a higher moral order. This movement toward creation of newer ideals and their fulfillment, is the substance of freedom : “life is an endeavor for freedom.” The ends toward which to endeavor, the sky for us to aspire to, is “the completest ego”, the Perfect Man. “In him the discord of our mental life becomes a harmony. The highest power is united in him with the highest knowledge.” Iqbal’s answer to the existential question of purpose is the Perfect Man, but hardly does it invoke Nietzsche’s ideal. First and foremost, Iqbal’s Perfect Man is moral. The striving to perfection is reflected in the struggle to complete oneself, through moral development of the self and becoming our desire-image. Further, this development of the self does not culminate in absorption of the individual into an universal oneness, but rather by the individual becoming more and more unique. “God himself is an individual: He is the most unique individual.” Finally, this striving is at the heart of all of humanity. The Perfect Man, the “viceregent of God on earth”, is within the reach of all, especially the impoverished masses of colonized India, to whom Iqbal wrote Asrar. Love and the Human Personality Iqbal’s message to the subjugated was to affirm the self and to know oneself. “There is a beloved hidden within thine heart: I will show him to thee, if thou hast eyes to see.” He rejects notions of self-negation, asserting that it is a notion invented by the weak to intellectually subdue the strong. The oppressor perpetuates the idea of self negation, because they seek to be free of the consequences of their moral violation. The subjugated self, on the other hand, needs courage and conviction in itself, so that it may participate in the movement of the world “from chaos to cosmos”, the creation and fulfilment of higher ideals. The self-knowledge necessary for living a life of purpose is rooted firmly in a deep sense of love. “My being was an unfinished statue, Uncomely, worthless, good for nothing. Love chiselled me: I became a man. And gained knowledge of the nature of the universe.” Why did Iqbal talk of love to a people robbed of their dignity, struggling to imagine a future? He saw love as a prerequisite to knowledge, and knowledge as a prerequisite to liberation. Love, in the highest sense, is the desire to “assimilate”, absorb what stands in the way of liberation and thereby overcome them. In oneself, it is the acceptance of imperfections, which is the only way to transcend them. This is why Iqbal talks of Love as a chisel: it forces us to deal with ourselves, by facing our reality so that it may be changed. “By the might of Love evoke an army, Reveal thyself on the Faran of Love, That the lord of the Ka’ba may show thee favour And make thee the object of the text, ‘Lo, I will appoint a viceregent on the earth’.” Liberation lies in the honest attempt to confront ourselves when the inner and outer worlds collide. The inner world of the self in fact continually develops through participation in the outer world, through the struggle to bring to life its desire-image. Iqbal offers us a talisman in times of moral quandary: the fortification of the human personality. The personality is the manifestation of the constant struggle between our essential aspirations and objective conditions, a “state of tension” between who we are, what we wish to become and the path set out for us by an unjust society. That which maintains the state of tension is morally permissible, that which reverts the personality to a state of relaxation, inaction or retreat from struggle, is not. It is moral principles that bind the self to the concrete world, and these principles can be discerned by their effect on the human personality. Moreover, the path toward the Perfect Man is open to all who are willing to “reveal”, or face themselves and their distance from their ideals. This confrontation of ourselves can only be sustained if we recognize that our ideals bind us to the world outside us. It is our very search for meaning that connects us to the rest of humanity, and isolation from humanity leads us astray from the search and distorts our personality. Here was a knot that now lay untied. Here was a philosophy that could be used to understand and transform oneself. Power and the centrality of Action “Subject, object, means, and causes – All these are forms which it assumes for the purpose of action. The self rises, kindles, falls, glows, breathes, Burns, shines, walks and flies.” “Power that is unexpressed and inert Chains the faculties which lead to action.” While Love and Knowledge prepares us for transformation, it is Action that can harness the power of the self and make that transformation a reality. The purview of Iqbal’s philosophy is neither metaphysics, nor a knowledge of the self for the sake of itself, but the concrete outer world. The inner self must be known so that it may be changed, and can act and be an agent of history. We are shaped by the moment of history we find ourselves in, and in turn act upon it. Iqbal was a part of the cultural awakening that galvanized the consciousness of masses of people and ultimately led to our freedom struggle. He rejected any philosophy that advocated inaction because he saw the fierce urgency of rejuvenation and participation of the masses in the democratic process to bring change. “Just as there are senses specific to colour, smell etc., there is another sense in human beings that ought to be called the ‘sense of events’. Our life depends on witnessing the events around us, correctly understanding from their cognitive content and adorning ourselves with actions.” Iqbal imbues new meaning to the knowledge of history and the historical process. The development of the outer world of man through the stages of history is the manifestation of the moral development of the inner world. This inner development manifests itself through action on the outer world, and moves history forward. He brings history to the doorstep of every humble self, and shows us how to participate in its creation. The purpose of knowledge of the self and of history is to guide us toward action, to transform ourselves and the world. “The pith of Life is contained in action, To delight in creation is the law of Life. Arise and create a new world !” Action in the broadest sense is the means to bring about a renewal, a creation of the new, a break with the mechanical logic of a philosophy whose time has passed, and which no longer serves the human personality. Iqbal points to the eternal “law of Life” whose logic is the perpetual renewal of ourselves through action. It is rooted in a sense of history which bears witness to this renewal of a people in times of crises. A Figure for Our Times We are witnessing an epoch of profound transition in history, from the era of enslavement and degradation of the majority of humanity to an era of new freedom and dignity for all. Today this transitory moment is reflected in the severe political crisis in almost all Western democracies, the rapid dismantling of political and economic hegemony of the US in the world, the geopolitical realignment of African and Middle Eastern nations, and the remarkable rise of Asia. The era that began with the Russian revolution, the Black freedom movement and anti-colonial movements the world over for political freedom, is now ripe with new possibilities for human freedom. Today, I no longer see the young boy dredging along garbage from our homes with his father who never had another job. Instead, there are young men, employed in varying capacities by the state, who drive by, under far more sanitized conditions and with more dignity, letting us dispose our own trash. The signs in our nation of the development of basic conditions of dignity for all and alleviation of poverty, is a part of the world movement from the era of empire to the age of humanity. They signify the unleashing of the potential of masses of ordinary people to make profound contributions to the world’s knowledge and thought. At the same time, this forward march of humanity toward a new stage of history brings new questions yet to be answered. What is the new stage going to look like? What are going to be the ideals we strive for? How are we going to see our role in the world? What examples shall we set for the future? These are not questions to be answered in the future but today. The birth of the new world in our time, as in every time, depends on the role we play in shaping it, and the extent to which we can transform ourselves. It is in the spirit of our responsibility to the new world and the new human being, that we must look to Iqbal and draw lessons from him for our times. He was first and foremost a revolutionary thinker, with a profound faith in humanity and its capacity to transform itself through love, knowledge and struggle. He gifted us with a new philosophy that can reintroduce us to our purpose in life, and thereby renew ourselves and liberate our minds from stagnation. He is even more relevant today because the masses of people, especially young people, are hungry for new ideas, and will not be satisfied with abstract philosophies that advocate retreat and perpetuate isolation. We are the inheritors of his ideas, and we are indebted to the faith he had in us, the future. It is our turn to bear his torch and let his ideas transform us as we contribute to shaping our future. Raza Mir Khudi ko kar buland itna, ke har taqdeer se pahle

Khuda bande se khud pooche, bata teri raza kya hai? Exalt your self thus, that before every twist of fate God should say, ‘My creation, on your desire I wait.’ If there is one concept that finds the most abundant expression in Iqbal’s poetry, it is that of khudi (selfhood). Taken at face value, the idea is a simple one. Iqbal thought of khudi as that essence of a person’s being that was left over when all relational aspects of their personality were set aside. A person’s name does not describe them completely. Nor do their linkages to their families, their ethnicities, their professions, their relationships, their cultural affinities and such. That aspect of a person’s being that exists beyond these relational webs is what Iqbal thought of as the true self, the khudi. According to him, everybody possessed a khudi; it is what they did with it that marked them as either free or enslaved, exalted or bowed, evolving or moribund. As the above verse suggests, Iqbal thought of khudi as a power through which human beings could determine their own fate and chart their own destiny. An exalted khudi connoted striving, individuality, originality and courage, characteristics that Iqbal found most worthy in the human race. Khudi: The Modern Self Iqbal’s poems repeatedly circle around the idea of khudi. For instance, he writes: Ye mauj-e-nafas kya hai, talvaar hai Khudi kya hai, talvaar ki dhaar hai Khudi kya hai, raaz-e daroon-e hayaat Khudi kya hai, bedaari-e kaayenaat Khudi jalva badmast-o khalvat-pasand Samundar hai ik boond paani meiN band … Khudi ka nasheman tere dil meiN hai Falak jis tarah aankh ke til meiN hai Khudi ke nigah-baaN ko hai zahr-naab Vo naaN jis se jaati rahe us ki aab Vahi naaN hai us ke liye arjumand Vahi jis se duniya meiN gardan buland Khudi faal-e-Mahmood se darguzar Khudi par nigah rakh Ayaazi na kar This flowing breath is but a sword What is selfhood but that sword’s sharp edge? Selfhood is life’s deepest secret Selfhood animates the universe itself Selfhood is wine-fuelled sharing, and secrecy too It is an ocean contained in a solitary droplet … The abode of selfhood lies in your heart Like the entire sky lies in the pupil of your eye That food earned at the cost of selfhood Verily, it is poison! The only food worthy of consumption is that Which allows you to stay with head unbowed in this world Selfhood disdains even kings like Mahmood Forsaking not just their pomp, but Ayaaz’s slavishness as well The above verses, excerpted from Iqbal’s famous poem Saaqi Naama (Ode to the Cupbearer), flesh out Iqbal’s idea of a selfhood that is proud to the point of vanity, and desires neither any special treatment nor shrinks from deprivation. The concept of khudi preoccupied Iqbal from a young age. His first book was titled Asraar-e Khudi (Signs of the Self), and his second book played off the concept as well. Even though Iqbal called it Rumooz-e Bekhudi (Enigmas of Selflessness), matters of selfhood were front and centre in it as well. For Iqbal, those humans who paid attention to their khudi and focused on strengthening and purifying it were centred beings who did not bow to those in power. They strove to become ideal humans, and their own will transcended the powers of determinism or taqdeer. They made their own luck and wrote their own fates. Those who compromised on their khudi were destined to eat the bread of slavery, to bow to beings other than their creator and to lead inauthentic, derivative lives. The idea of khudi, however, was not just a philosophical concept, but also a tool for a specific political intervention. Iqbal was coming of age as a thinker at a time when Indians were experiencing the humiliation of colonial conquest. It was but natural for them to reflect on what had gone wrong, and what they needed to do to get out of their predicament. Indian thinkers were grappling with this problem. Swami Vivekananda, a contemporary of Iqbal, was attempting to articulate a new Hinduism that would be able to resist colonial conquest. Muslim thinkers like Syed Ahmed Khan (1817–1898) were wrestling with similar issues. The dominant theme among Muslim modernists was that the community had discarded reason, a cornerstone of Islamic thought. They felt that Westerners had become powerful because they had embraced this very quality that Muslims had abjured. Iqbal, however, was not so enamored of this idea. He disdained the idea of a rationality that was not anchored by belief and spirituality. Instead, he developed the concept of khudi, which incorporated elements of reason along with a sense of spiritual revival and intuition. For him, a person with a strong khudi possessed a clear sense of self combined with a deep belief in God and divinity. A healthy khudi incorporated a strong ego with deep devotion. It was independent, evolving and modern, but was also religious and spiritually inclined. For Iqbal, there was a continuity between the acme of human potential and divinity itself. In the words of one of his intellectual biographers Hafiz Malik, ‘for Iqbal, man becomes unique by becoming more and more like the most unique individual [God]’. The concept of khudi has an earlier history in Sufi thought and is associated with thinkers such as the Iranian mystic Fariduddin Attar (1145–1221). Attar’s famous quote, Ehf az khudi un khuda sheefast, ‘selfhood has become my god; I need no god of yours’, is a famous Sufi proclamation. Attar was one of the first who had connected the human to the divine: Har rag-e-jaaN taar gushta, haajat-e zunnaar neest, every vein of my body connects me to the divine; I no longer need a sacred thread. While Iqbal was struck by the manner in which Attar saw humans as possessing the potential for divinity within themselves, he layered the Attarian khudi with Western/modernist ideas to produce a concept that he felt was more attuned to the contemporary world. Iqbal considered himself a follower of Sufi tradition, but for him, Sufism contained two dominant strands. The first one, which he derided as ‘pantheistic’ was represented by the philosophy of the twelfth-century mystic Ibn-e Arabi and his concept of wahdat-ul wujood. This approach demanded that the individual dissolve their personality into a collective/divine self. Iqbal found this approach unacceptable, derided it as quietist and decadent and blamed it (along with greed and indolence) as the primary reason for the decline of Muslims. The Sufism he advocated was beholden to the thirteenth-century mystic Jalaluddin Rumi, whose method he considered ‘active’. In his understanding, the passivity of Ibn-e Arabi and his followers had reduced religious subjecthood to ‘nothingness’. Instead, following Sufi thinkers like Rumi and Attar, he placed the human on an evolutionary continuum, the ultimate end of which was God. One of the best-regarded masters of the Sufi tradition is Mansour al-Hallaj, the ninth-century mystic whose pronouncement of Ana-al Haq (‘I am the Truth’) was misinterpreted as apostasy (‘I am Truth’ was taken to mean ‘I am God’) by the Abbasid caliph Al-Muqtadir, leading to Hallaj’s execution. The Ibn-e Arabi Sufis interpreted Hallaj’s statement as saying that he had drowned himself in the divine. Iqbal begged to differ, suggesting ‘the true interpretation of [Hallaj’s] experience, therefore, is not a drop slipping into the sea, but the realization and bold affirmation … of the reality and permanence of the human ego in a profounder personality’. In other words, rather than seeing the drop as dissolving in the ocean, Iqbal encouraged the human to see the ocean in the drop they symbolized. This could be done only if the drop saw itself as unique. Other modernist thinkers had made similar statements, but Iqbal wished to locate the ego alongside a steadfast belief in the divine. A simple arithmetic may explain things: For Iqbal, the modernist notions of ego plus the spiritual understanding of the divine plus submission to it equalled a strong khudi. The world for Iqbal was ever evolving, and in order to achieve their potential, humans needed to evolve with it: Ye kaayenaat abhi naa-tamaam hai shaayad Ke aa rahi hai damaadam sadaa-e kun-fayakooN This universe is still a work in progress maybe For there still echo commands of ‘become’ and ‘be’ Modernity was everywhere. It was transforming modes of production and economic activity, socio-political relationships, power equations and human psychology. To remain contemporary, relevant and inventive, human beings had to transform themselves, without losing their identity, their sense of self. Khudi was the force that allowed humans to evolve alongside the world, without losing their identity. Iqbal’s Khudi: A Critical Analysis Iqbal’s concept of khudi was an important intervention in Sufi debates. He framed a binary between the passive Sufis (where he also placed the notable fourteenth-century poet Hafez, criticising his work as a cup that was ‘full of the poison of death’) and the active ones (where he placed Rumi, who he considered his spiritual teacher). One is not very clear whether this bifurcation was a result of a near-deliberate misinterpretation of the symbolism of Farsi poetry, which might have emerged from an unacknowledged influence of Western philosophy. Iqbal’s thought was a constant attempt to understand Eastern philosophy in light of Western ideas and vice versa. Occasionally, he did succumb to the tendency to evaluate one system according to the yardsticks of the other. For example, his critics have commented on the fact that often, Iqbal’s concept of khudi was excessively beholden to the ideas of the seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes, who saw reason as being materially anchored. They implied that despite Iqbal’s protestations, his khudi is mostly a Western derivative. They also faulted his excessive preoccupation with reconceptualizing Islamic ideas in the age of colonialism. Likewise, while Iqbal’s s idealism and optimism breathes life into the concept of khudi, it is difficult not to see in his articulation a sense of impatience with those who are cheated and defeated by circumstance. Studying the corpus of Iqbal’s poetry and prose on khudi, one cannot help feeling that he was needlessly scornful of contemporary Muslims and Muslim polity. Iqbal inhabited a world where the global Muslim psyche was in retreat. The empires of the Middle East were being routed in battle after battle by European powers. In the subcontinent, the space for Muslim self-expression was shrinking with every political compromise struck between the Indians and the British, as Indians grappled with the inevitability of decolonization. Moreover, Iqbal perceived Muslims as having become passive, cowardly and whiny. In short, they could use an injection of the right kind of khudi, which he was ready to administer. One could be forgiven for thinking that some of of Iqbal’s verses that excoriated Muslims for being lazy and past-beholden were needlessly hectoring, arrogant and judgmental. To return to the sher that we began this chapter with, two of Iqbal’s ideas are on display in that verse: his conviction that adherence to the principles of truth, morality and action can overcome misfortune, and his implication that taqdeer (fate) was nothing but an excuse. In this sher and other ruminations on selfhood, Iqbal is positioning khudi against Sufi ideas of fana, where the individual sacrifices the self to achieve the divine. Iqbal saw khudi as the ocean itself, albeit in a drop, as the earlier verses in Saqi Naama show. He elaborates further in the matla of one of his ghazals: Khudi vo bahr hai jis ka koi kinaara nahiN Tu aabjoo ise samjha agar to chaara nahiN Selfhood is a boundless ocean without shore Be not foolish; think of it a stream no more It is not as if Iqbal was unfamiliar with the structural constraints faced by the masses. He was aware of the depredations of capitalism, and the ways in which the owners of wealth rendered the efforts of the working class fruitless. We may recall his clarion words in Khizr-e Raah (The Way of the Prophet): Banda-e mazdoor ko ja kar mera paighaam de Khizr ka paighaam kya hai ye payaam-e kaayenaat Ai ki tujh ko kha gaya sarmaayadaar-e heelagar Shaakh-e-aahoo par rahi sadiyoN talak teri baraat Convey my message to the toiling labourer It is not the prophet’s word, but the word of the universe You who were swallowed whole by the cunning capitalist Your wealth was as if pierced on the antlers of a deer What then caused him to discount the real obstacles faced by those whose problem was not one of self-realization, but the mere act of keeping their body and soul together? Could he not summon up some more empathy for those victims of capitalism and racism who were not so much being struck down by fate as being held back by structural barriers to mobility? The puzzle of Iqbal must remain unresolved in this respect. It is worthwhile reiterating that Iqbal’s German sojourn had put him in close touch with the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche. He was too much of an original thinker to be beholden to another philosopher’s ideas, but the idea of khudi as articulated by him owes at least some of its colour to the Nietzschean idea of self-improvement as man strives to transform into Superman. Unlike Nietzsche, however, Iqbal locates the fulcrum of selfhood in the belief in God. In his words: Khudi ka sirr-e-nihaaN laa-ilaaha-illallaah Khudi hai tegh fasaaN laa-ilaaha-illallaah The secret origin of the self: ‘There is no God but Allah’ The self is a sword, its whetstone: ‘There is no God but Allah’ Iqbal wants it every way. On the one hand, the Western idea of individualism animates khudi, but on the other hand, Iqbal is clear that without adherence to the protocols of faith and spirituality (which are essentially collectivist), the individual cannot achieve their potential. Likewise, while he is sympathetic to the idea that powerful structural forces are arrayed against the subalterns, he is not averse to some ‘you are responsible for your own misfortune’ finger wagging. This issue we don’t have an article on current world events and their understanding. Nevertheless, several very important shifts have happened just over the past few months which we must pay attention to. These include recent coups in Niger and Gabon, America’s deepening political crisis, the BRICS summit, increasing tensions between India and the West, the failed Ukrainian counter-offensive, and the meeting between Kim Jong Un and Vladimir Putin. Below, we suggest a few articles that cover these events

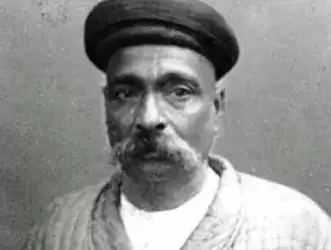

Pepe Escobar Welcome to the Brics 11 https://new.thecradle.co/articles/welcome-to-the-brics-11 M.K. Bhadrakumar India won’t be bullied in a multipolar setting https://www.indianpunchline.com/india-wont-be-bullied-in-multipolar-setting/ John Marsheimer Bound to Lose https://mearsheimer.substack.com/p/bound-to-lose Anthony Monteiro America’s Domestic Political Crisis https://forpositivepeaceblog.wordpress.com/2023/08/22/americas-domestic-political-crisis-the-greatest-threat-to-u-s-empire-saturday-free-school-july-15-2023/ Full Text Transcript of Meeting Between Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un https://www.miragenews.com/full-text-transcript-of-putin-kim-jong-un-1083492/ Text of Speech given by Ibrahim Traore, president of Burkina Faso at the Russia-Africa Summit https://peoplesdispatch.org/2023/08/02/a-slave-who-cannot-assume-his-own-revolt-does-not-deserve-to-be-pitied-says-ibrahim-traore-of-burkina-faso/ Archishman Raju  In one of many bustling streets in the center of Pune lies Kesari Wada, the home of one of our great freedom fighters, Bal Gangadhar Tilak. It is a big building but still almost hidden among the various shops, hostels and buildings that cover the street. The house has been converted into a museum, showing the original machine used for the printing of the newspaper that he co-founded, Kesari, a large bronze statue of him, copies of his original handwritten manuscripts and letters from the likes of Sarojini Naidu and Subramaniam Bharathi, and some information about his life and associates. There is a statue of Ganpati and a photo of Lenin among the exhibits. There are few visitors and only one person sitting at the desk who shuts the museum down as it becomes time for lunch. On visiting Tilak’s former house, one feels both overwhelmed and disappointed. Overwhelmed at the weight of history that we carry and disappointed that the state of the museum is perhaps symbolic that our history has not been fully realized. To move forward as a nation and a civilization we must fully understand what shaped us. To understand Bal Gangadhar Tilak is a necessary part of a proper understanding of the Indian revolution. The Early Years: Education and Propaganda Tilak was born in 1856 in Maharashtra, a year before the 1857 revolt. The period after his birth was a remarkably brutal period of British rule. In the second half of the 19th century, British rule led to close to 50 million Indian deaths as a result of famines. At the same time it saw the emergence of a class of Indians who were enamored by western culture. Many of them saw the salvation of Indian society in the adoption and imitation of western culture. This is the context in which Tilak’s role must be understood. Tilak had a sensitive personality and was deeply affected by the state of the country. As he said later, “We were men, with our brains in a fever heat with the thoughts of the degraded condition of our country and after long cogitation we had formed the opinion that the salvation of our motherland was to be found in education alone.” With his friend Agarkar, he decided to start the New English School under the guidance of well-known Maharashtrian personality V. Chipulankar. Alongside the school, Tilak and his colleagues started two newspapers in 1881, one in Marathi, Kesari (meaning The Lion) and the other in English called Mahratta. The purpose of Kesari was to have “articles on the condition of the people” and “a summary of the political happenings discussed in England” alongside the usual news. Kesari quickly became a very popular newspaper. This was the first stage of Tilak’s struggle as he focussed on education and propaganda as the means to liberate his people. In 1882, Tilak faced imprisonment for four months for material published in Kesari, which would be the first of many terms that he would spend in prison. By 1885, Tilak had reached the conclusion that the political struggle against British rule was of foremost importance. It should be noted that this was a time when the bulk of the Indian intelligentsia was focused on social reform of Indian society, rather than political struggle against the British. Tilak’s view was clear, “there had been such a degeneration owing to our slavery that the social condition of the people could not improve until their political condition was bettered and, therefore, an exhortation to concentrate on social reform to the exclusion of political reform was suicidal”. Thus Tilak made the argument that political struggle must precede social reform. In this, Tilak was ideologically far advanced of his contemporaries. Further, Tilak showed a tendency to associate himself with the masses of people rather than the British elite. As he said “there has been much talk about social reforms. But we have to bear in mind that we have to reform the masses and if we dissociate ourselves from them, reforms would become impossible”. Tilak also realized the need for national festivals which could bring together and unite the masses. He was responsible for starting “The Ganesh Festival” which remains immensely popular today. In 1896, India suffered another devastating famine including in the Maharashtra region. As Tilak wrote “The poverty of India is wholly due to the present rule. India is being bled till only the skeleton remains”. Following the famine, there was a plague in Bombay and Pune. Tilak was arrested again for his work in the Kesari which criticized the government and its response. He emerged from prison a national hero who was experienced in political struggle. Asian Unity and the battle for Swaraj The period after around 1905 was the second stage in Tilak’s political evolution. Japan’s war over Tsarist Russia had an important effect on Asian consciousness. In an article titled ‘Unity of Thought Among the People of the East’, Tilak had written “India formed the skeleton with sticks, the paper covering the sticks was China, and Japan was the nail that kept the sticks together”. At the same time, he got in touch with the Russian Consul in Bombay on the possibility of training Indians in Russian military schools. On the onset of the 1905 democratic revolution in Russia, Tilak wrote of the impressive organization of workers, students and other classes against the Tsar and often referred to it in his speeches as an example for India to learn from. In India, 1905 was the year Bengal was partitioned. This affected the consciousness of masses around the country. Tilak pushed the Congress party away from a politics of petitioning the British towards a politics of mass struggle. This was the time when the ideas of Swaraj and Swadeshi entered Indian politics. As Tilak said “If you mean to be free, you can be free…if you have not the power of active resistance, have you not the power of self-denial and self-abstinence in such a way as not to assist this foreign Government to rule over you? This is boycott…” In defining Swadeshi he said “one must look on all lines--whether political or industrial or economical--which converse our people towards the status of a civilised nation.” Tilak was brought to trial in 1908 for sedition. He was accused of supporting in the Kesari, bombs thrown by two young Bengali men in an attempt to assassinate a British judge. Tilak mounted a magnificent defense at his trial extending over 6 days. It was clear that he saw the trial as a political rather than a legal battle. Towards the end of his defense, he said to the jury “And I ask you to help us, not me personally, but the whole of India in our endeavours to obtain a share in the Government of this country. The matter has come to a critical stage; we are in want of help; you can give it to us. I am now on the wrong side of life according to the Indian standard of life. For me it can only be a matter of a few years, but future generations will look to your verdict and see whether you have judged wrong or right. The verdict is likely to be a memorable one in the history of the struggle for the freedom of the Indian Press. You have a heavy responsibility upon you. It is, I state again and again, not a personal question.” The jury of 7 Europeans and 2 Indians found him guilty 7:2. The Indian Press condemned the verdict and supported Tilak. The masses of people were outraged and the verdict led to the Bombay Textile Worker strike in 1908 which was brutally repressed. The working class as a whole came out to support Tilak. Lenin, writing of world events in 1908 said “There Is no end to the acts of violence and plunder which goes under the name of the British system of government in India…But in India the street is beginning to stand up for its writers and political leaders. The infamous sentence pronounced by the British jackals on the Indian democrat Tilak…this revenge against a democrat by the lackeys of the money-bag evoked street demonstrations and a strike in Bombay.” Gita Rahasya and Karma Yoga Tilak was sentenced to prison in Myanmar for a period of 6 years. It is here that his philosophical ideas found full expression with the writing of his commentary on the Gita, Gita Rahasya. It should be noted that Tilak wrote this book in utterly abject conditions. As Subhash Chandra Bose, who spent time in the same prison, wrote later, the prison would have unbearable heat in the summer, often get flooded during rains, and bitterly cold in the winter. Tilak was put virtually under solitary confinement in what Bose described as a cage. Tilak’s interpretation of the Gita is a work of genius. It shows Tilak’s vast reading in philosophy including Western philosophy. It should be noted that the central message of the Gita is Yoga, a word whose original meaning is the uniting of atman and brahman, of the individual soul with the soul of the cosmos. This is the path to moksha or liberation. Traditionally, different schools of thought have emphasized different paths to liberation but the most prominent ones had been the path of knowledge by Shankar and the path of bhakti or love/devotion by Ramanuja. Tilak instead proposed that the main message of the Gita was karma or the path of action. He proposed that the essence of the Gita was action, which was guided and united by knowledge and love. This action must not seek any reward for the individual self. It was in following the path of Karma Yoga that Tilak believed Indians would proceed towards Swaraj or self-rule. Tilak refused to believe that his religion taught a life of renunciation and meditation. He said “it is my thesis that Swaraj in the life to come cannot be the reward of a people who have not enjoyed it in this world…God does not help the indolent. You must be doing all that you can to lift yourself up…You should not, however, presume that you have to toil that you yourself might reap the fruits of your labour…Let us then try our utmost and leave the generations to come to enjoy that fruit.” As Mahatma Gandhi said in his own interpretation of the Gita, “This is the unmistakable teaching of the Gita. He who gives up action falls.” Therefore, Tilak, and Gandhi after him understood that religion in the best sense encouraged political action in the interest of truth, justice and freedom. The legacy of Tilak Today Indian society is deeply immersed in its history. The intense historical debates that our society faces are rarely about the past, they are essentially about our present identity. No period of Indian history is uncontested, seemingly every date of our texts is undetermined. Every debate on our history as it exists today can be traced back to colonialism and the subsequent freedom struggle. Our freedom struggle started the process of grappling with our history and every generation must revisit this quest anew. And yet today we are faced with a time when our freedom struggle itself, a seemingly incontestable inheritance, is being called into question. Indian intellectuals of varying ideological persuasions seem determined to belittle the mainstream of our freedom struggle. Further, our intellectual discourse suffers from a curious amnesia. Major events of our freedom struggle are discussed with almost no reference to British imperialism. The battle for our history is enmeshed with the battle of ideas. Our history is a weapon in this battle and a proper understanding of our freedom struggle is essential to move forward. The legacy of Tilak is important today because of his uncompromising struggle against western imperialism. His legacy is important because of his philosophical ideas which ask us to struggle for freedom in this world. His legacy is important because of his immense faith in the Indian people and India’s civilization. We must accord him the proper place he holds in the history of our freedom struggle. References Gita Rahasya (Hindi) by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, tr. Madhavrao Sapre Lokmanya Tilak A Biography by A. K. Bhagwat and G. P. Pradhan Bal Gangadhar Tilak, His Writings and Speeches The Bhagavad Gita According to Gandhi Reminiscences and Anecdotes of Lokamanya Tilak ed. S. V. Bapat Full & Authentic Report of the Tilak Trial published by N. C. Kelkar The Russian Revolution and India Ed. Ilasai Manian and V. Rajesh Inflammable Material in World Politics, V. I. Lenin |

CategoriesArchives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed