|

Sambarta Chatterjee I have always been drawn to the idea that our inner worlds, our selves, are not a thing apart from our outer lives: we derive a sense of purpose and meaning from our inner world, a meaning that is necessary to navigate the world and which informs the lives we lead. I felt that in order to live a meaningful life, our inner world must be known and studied, and this knowledge is self-contained. Ultimately, noone could know me better than myself, and this knowledge could only come from delving inwards. I was fascinated by philosophical musings on the meaning of life and the connections and contradictions between the inner and outer life, and in searching for a framework quickly came across the 20th century European existentialists. I was heavily impressed by them. I shared in their ‘discovery’ of the fact that the essence of man, the search for meaning, lay in contradiction to the reality of our outer, ‘existential’ nature. My idea of who I wanted to be always seemed to clash with who I really was. The existential question of how to bridge that gap was a serious question, and I tried to go where Camus or Sartre would take me. The impression that existentialism bore upon me was that this journey was definitely an individual one. I was convinced that these questions were the purview of a small minority of people, who were necessarily isolated from their surrounding world and the majority of humanity. It seemed a logical conclusion that our place, and role, in the outer, objectively real world, could help little in answering the questions I was struggling with. This idea seemed strangely comforting, since it freed me from the responsibility of making myself understood to the world around me. This comfort was nevertheless sustained by the fact that there were others, even if few, who shared this conviction.

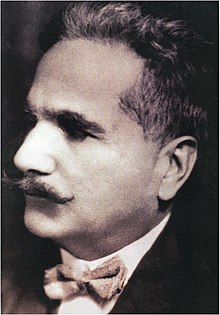

But did I truly hold this conviction? I found myself increasingly incapable of isolating myself from the world, from those who lived ordinary and beautiful lives, different from my own. I couldn’t convince myself that my lifeworld was fundamentally different from ordinary people, poor and struggling, like the young boy who accompanied his janitor father in garbage collection in my neighborhood under the most immiserating (and seemingly permanent) conditions. I was told by Sartre that “existence precedes essence”, but I saw that that boy had aspirations not very different from mine, in spite of his existential conditions, and knew that poor people everywhere strove for both bread and beauty. Was I truly convinced that “the one truly serious philosophical problem is that of suicide”, as Camus would have us believe? What of poverty and suffering? What of love and struggle? If existential anguish was irreducible, what was the way forward? Camus’ answer of embracing the absurd gave me absolutely nothing, for there was nothing remotely absurd about poverty or love, nor in the struggle to rise above degradation which characterized the lives of millions. The earlier comfort that came with an adolescent indifference to the world, seemed to be waning. I sensed that my notions about philosophy were at odds with the life I wanted to lead, to participate and be involved in the lifeworld of people. What then was the purpose of philosophy? Were questions of the inner world, a sense of self, after all futile? And yet I knew I did have an inner world which had to be understood, which was not irrelevant to the outer world of degradation and aspirations. In searching for a philosophical framework that can accommodate the whole reality of the world I see, I had to look toward the traditions that produced me and the others of my generation: the anticolonial and antiracist freedom movements of the 20th century. Muhammad Iqbal is a towering figure rooted in this tradition. His ideas serve to illuminate the dark alleys that existentialism may lead us to, and his revolutionary answers to questions of the inner world can transform us and lead us to light. Fortification of the self – to what end ? Iqbal wrote Asrar-e-Khudi (‘Secrets of the Self’) in 1915, speaking to a subject people of a nation yet to be, whose sense of themselves was being perpetually distorted by a colonial system that controlled every aspect of their lives. What passed for education was a series of racist policies designed to indoctrinate the intellectual class into participating in their own subjugation and breed a sense of inferiority and desolation among the masses. The inner world of an oppressed people seemed all but irrelevant to the outer reality of colonialism, and yet Iqbal urged to delve inward and strengthen a sense of self. “Tho’ I am but a mote, the radiant sun is mine: Within my bosom are a hundred dawns. My dust is brighter than Jamshid’s cup It knows things that are yet unborn in the world.”' To the most downtrodden and disinherited, Iqbal’s words are a reminder of their true power and agency. The disinherited knows the rightful place of man in the world, which is yet to be manifested in reality. The human condition, the contradiction between our sense of self and our outer existential condition is most profound in the oppressed. And Iqbal offers a way out, from the inner desolation and outer devastation by radically reintroducing the meaning of Life itself. “Life is preserved by purpose: Because of the goal its caravan-bell tinkles. Life is latent in seeking, Its origin is hidden in desire. Keep desire alive in thy heart, Lest thy little dust become a tomb.” The purpose of life is “the creation of values and ideals and the endeavor to realize them”, the ends for which one must strengthen the self by recognizing its true potential. The search for meaning and the struggle to become ourselves is inseparably tied to “desire” or ideals, a sense of morality. The sense of morality is at once internal and external. It pertains to the outer world and our participation in it, but we are active participants in its creation. The inner world of the individual is therefore not only a part of, but is capable of making a contribution to and shaping the objective outer world. The price of the contribution is the recognition of our incompleteness, the chasm between our desire-image and who we really are. And the movement of life, for the individual and for humanity, is to overcome this incompleteness, by bringing about a higher moral order. This movement toward creation of newer ideals and their fulfillment, is the substance of freedom : “life is an endeavor for freedom.” The ends toward which to endeavor, the sky for us to aspire to, is “the completest ego”, the Perfect Man. “In him the discord of our mental life becomes a harmony. The highest power is united in him with the highest knowledge.” Iqbal’s answer to the existential question of purpose is the Perfect Man, but hardly does it invoke Nietzsche’s ideal. First and foremost, Iqbal’s Perfect Man is moral. The striving to perfection is reflected in the struggle to complete oneself, through moral development of the self and becoming our desire-image. Further, this development of the self does not culminate in absorption of the individual into an universal oneness, but rather by the individual becoming more and more unique. “God himself is an individual: He is the most unique individual.” Finally, this striving is at the heart of all of humanity. The Perfect Man, the “viceregent of God on earth”, is within the reach of all, especially the impoverished masses of colonized India, to whom Iqbal wrote Asrar. Love and the Human Personality Iqbal’s message to the subjugated was to affirm the self and to know oneself. “There is a beloved hidden within thine heart: I will show him to thee, if thou hast eyes to see.” He rejects notions of self-negation, asserting that it is a notion invented by the weak to intellectually subdue the strong. The oppressor perpetuates the idea of self negation, because they seek to be free of the consequences of their moral violation. The subjugated self, on the other hand, needs courage and conviction in itself, so that it may participate in the movement of the world “from chaos to cosmos”, the creation and fulfilment of higher ideals. The self-knowledge necessary for living a life of purpose is rooted firmly in a deep sense of love. “My being was an unfinished statue, Uncomely, worthless, good for nothing. Love chiselled me: I became a man. And gained knowledge of the nature of the universe.” Why did Iqbal talk of love to a people robbed of their dignity, struggling to imagine a future? He saw love as a prerequisite to knowledge, and knowledge as a prerequisite to liberation. Love, in the highest sense, is the desire to “assimilate”, absorb what stands in the way of liberation and thereby overcome them. In oneself, it is the acceptance of imperfections, which is the only way to transcend them. This is why Iqbal talks of Love as a chisel: it forces us to deal with ourselves, by facing our reality so that it may be changed. “By the might of Love evoke an army, Reveal thyself on the Faran of Love, That the lord of the Ka’ba may show thee favour And make thee the object of the text, ‘Lo, I will appoint a viceregent on the earth’.” Liberation lies in the honest attempt to confront ourselves when the inner and outer worlds collide. The inner world of the self in fact continually develops through participation in the outer world, through the struggle to bring to life its desire-image. Iqbal offers us a talisman in times of moral quandary: the fortification of the human personality. The personality is the manifestation of the constant struggle between our essential aspirations and objective conditions, a “state of tension” between who we are, what we wish to become and the path set out for us by an unjust society. That which maintains the state of tension is morally permissible, that which reverts the personality to a state of relaxation, inaction or retreat from struggle, is not. It is moral principles that bind the self to the concrete world, and these principles can be discerned by their effect on the human personality. Moreover, the path toward the Perfect Man is open to all who are willing to “reveal”, or face themselves and their distance from their ideals. This confrontation of ourselves can only be sustained if we recognize that our ideals bind us to the world outside us. It is our very search for meaning that connects us to the rest of humanity, and isolation from humanity leads us astray from the search and distorts our personality. Here was a knot that now lay untied. Here was a philosophy that could be used to understand and transform oneself. Power and the centrality of Action “Subject, object, means, and causes – All these are forms which it assumes for the purpose of action. The self rises, kindles, falls, glows, breathes, Burns, shines, walks and flies.” “Power that is unexpressed and inert Chains the faculties which lead to action.” While Love and Knowledge prepares us for transformation, it is Action that can harness the power of the self and make that transformation a reality. The purview of Iqbal’s philosophy is neither metaphysics, nor a knowledge of the self for the sake of itself, but the concrete outer world. The inner self must be known so that it may be changed, and can act and be an agent of history. We are shaped by the moment of history we find ourselves in, and in turn act upon it. Iqbal was a part of the cultural awakening that galvanized the consciousness of masses of people and ultimately led to our freedom struggle. He rejected any philosophy that advocated inaction because he saw the fierce urgency of rejuvenation and participation of the masses in the democratic process to bring change. “Just as there are senses specific to colour, smell etc., there is another sense in human beings that ought to be called the ‘sense of events’. Our life depends on witnessing the events around us, correctly understanding from their cognitive content and adorning ourselves with actions.” Iqbal imbues new meaning to the knowledge of history and the historical process. The development of the outer world of man through the stages of history is the manifestation of the moral development of the inner world. This inner development manifests itself through action on the outer world, and moves history forward. He brings history to the doorstep of every humble self, and shows us how to participate in its creation. The purpose of knowledge of the self and of history is to guide us toward action, to transform ourselves and the world. “The pith of Life is contained in action, To delight in creation is the law of Life. Arise and create a new world !” Action in the broadest sense is the means to bring about a renewal, a creation of the new, a break with the mechanical logic of a philosophy whose time has passed, and which no longer serves the human personality. Iqbal points to the eternal “law of Life” whose logic is the perpetual renewal of ourselves through action. It is rooted in a sense of history which bears witness to this renewal of a people in times of crises. A Figure for Our Times We are witnessing an epoch of profound transition in history, from the era of enslavement and degradation of the majority of humanity to an era of new freedom and dignity for all. Today this transitory moment is reflected in the severe political crisis in almost all Western democracies, the rapid dismantling of political and economic hegemony of the US in the world, the geopolitical realignment of African and Middle Eastern nations, and the remarkable rise of Asia. The era that began with the Russian revolution, the Black freedom movement and anti-colonial movements the world over for political freedom, is now ripe with new possibilities for human freedom. Today, I no longer see the young boy dredging along garbage from our homes with his father who never had another job. Instead, there are young men, employed in varying capacities by the state, who drive by, under far more sanitized conditions and with more dignity, letting us dispose our own trash. The signs in our nation of the development of basic conditions of dignity for all and alleviation of poverty, is a part of the world movement from the era of empire to the age of humanity. They signify the unleashing of the potential of masses of ordinary people to make profound contributions to the world’s knowledge and thought. At the same time, this forward march of humanity toward a new stage of history brings new questions yet to be answered. What is the new stage going to look like? What are going to be the ideals we strive for? How are we going to see our role in the world? What examples shall we set for the future? These are not questions to be answered in the future but today. The birth of the new world in our time, as in every time, depends on the role we play in shaping it, and the extent to which we can transform ourselves. It is in the spirit of our responsibility to the new world and the new human being, that we must look to Iqbal and draw lessons from him for our times. He was first and foremost a revolutionary thinker, with a profound faith in humanity and its capacity to transform itself through love, knowledge and struggle. He gifted us with a new philosophy that can reintroduce us to our purpose in life, and thereby renew ourselves and liberate our minds from stagnation. He is even more relevant today because the masses of people, especially young people, are hungry for new ideas, and will not be satisfied with abstract philosophies that advocate retreat and perpetuate isolation. We are the inheritors of his ideas, and we are indebted to the faith he had in us, the future. It is our turn to bear his torch and let his ideas transform us as we contribute to shaping our future.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

CategoriesArchives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed