|

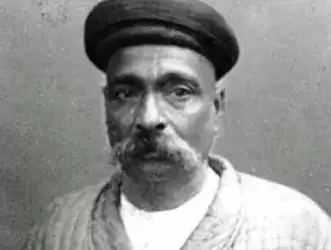

Archishman Raju  In one of many bustling streets in the center of Pune lies Kesari Wada, the home of one of our great freedom fighters, Bal Gangadhar Tilak. It is a big building but still almost hidden among the various shops, hostels and buildings that cover the street. The house has been converted into a museum, showing the original machine used for the printing of the newspaper that he co-founded, Kesari, a large bronze statue of him, copies of his original handwritten manuscripts and letters from the likes of Sarojini Naidu and Subramaniam Bharathi, and some information about his life and associates. There is a statue of Ganpati and a photo of Lenin among the exhibits. There are few visitors and only one person sitting at the desk who shuts the museum down as it becomes time for lunch. On visiting Tilak’s former house, one feels both overwhelmed and disappointed. Overwhelmed at the weight of history that we carry and disappointed that the state of the museum is perhaps symbolic that our history has not been fully realized. To move forward as a nation and a civilization we must fully understand what shaped us. To understand Bal Gangadhar Tilak is a necessary part of a proper understanding of the Indian revolution. The Early Years: Education and Propaganda Tilak was born in 1856 in Maharashtra, a year before the 1857 revolt. The period after his birth was a remarkably brutal period of British rule. In the second half of the 19th century, British rule led to close to 50 million Indian deaths as a result of famines. At the same time it saw the emergence of a class of Indians who were enamored by western culture. Many of them saw the salvation of Indian society in the adoption and imitation of western culture. This is the context in which Tilak’s role must be understood. Tilak had a sensitive personality and was deeply affected by the state of the country. As he said later, “We were men, with our brains in a fever heat with the thoughts of the degraded condition of our country and after long cogitation we had formed the opinion that the salvation of our motherland was to be found in education alone.” With his friend Agarkar, he decided to start the New English School under the guidance of well-known Maharashtrian personality V. Chipulankar. Alongside the school, Tilak and his colleagues started two newspapers in 1881, one in Marathi, Kesari (meaning The Lion) and the other in English called Mahratta. The purpose of Kesari was to have “articles on the condition of the people” and “a summary of the political happenings discussed in England” alongside the usual news. Kesari quickly became a very popular newspaper. This was the first stage of Tilak’s struggle as he focussed on education and propaganda as the means to liberate his people. In 1882, Tilak faced imprisonment for four months for material published in Kesari, which would be the first of many terms that he would spend in prison. By 1885, Tilak had reached the conclusion that the political struggle against British rule was of foremost importance. It should be noted that this was a time when the bulk of the Indian intelligentsia was focused on social reform of Indian society, rather than political struggle against the British. Tilak’s view was clear, “there had been such a degeneration owing to our slavery that the social condition of the people could not improve until their political condition was bettered and, therefore, an exhortation to concentrate on social reform to the exclusion of political reform was suicidal”. Thus Tilak made the argument that political struggle must precede social reform. In this, Tilak was ideologically far advanced of his contemporaries. Further, Tilak showed a tendency to associate himself with the masses of people rather than the British elite. As he said “there has been much talk about social reforms. But we have to bear in mind that we have to reform the masses and if we dissociate ourselves from them, reforms would become impossible”. Tilak also realized the need for national festivals which could bring together and unite the masses. He was responsible for starting “The Ganesh Festival” which remains immensely popular today. In 1896, India suffered another devastating famine including in the Maharashtra region. As Tilak wrote “The poverty of India is wholly due to the present rule. India is being bled till only the skeleton remains”. Following the famine, there was a plague in Bombay and Pune. Tilak was arrested again for his work in the Kesari which criticized the government and its response. He emerged from prison a national hero who was experienced in political struggle. Asian Unity and the battle for Swaraj The period after around 1905 was the second stage in Tilak’s political evolution. Japan’s war over Tsarist Russia had an important effect on Asian consciousness. In an article titled ‘Unity of Thought Among the People of the East’, Tilak had written “India formed the skeleton with sticks, the paper covering the sticks was China, and Japan was the nail that kept the sticks together”. At the same time, he got in touch with the Russian Consul in Bombay on the possibility of training Indians in Russian military schools. On the onset of the 1905 democratic revolution in Russia, Tilak wrote of the impressive organization of workers, students and other classes against the Tsar and often referred to it in his speeches as an example for India to learn from. In India, 1905 was the year Bengal was partitioned. This affected the consciousness of masses around the country. Tilak pushed the Congress party away from a politics of petitioning the British towards a politics of mass struggle. This was the time when the ideas of Swaraj and Swadeshi entered Indian politics. As Tilak said “If you mean to be free, you can be free…if you have not the power of active resistance, have you not the power of self-denial and self-abstinence in such a way as not to assist this foreign Government to rule over you? This is boycott…” In defining Swadeshi he said “one must look on all lines--whether political or industrial or economical--which converse our people towards the status of a civilised nation.” Tilak was brought to trial in 1908 for sedition. He was accused of supporting in the Kesari, bombs thrown by two young Bengali men in an attempt to assassinate a British judge. Tilak mounted a magnificent defense at his trial extending over 6 days. It was clear that he saw the trial as a political rather than a legal battle. Towards the end of his defense, he said to the jury “And I ask you to help us, not me personally, but the whole of India in our endeavours to obtain a share in the Government of this country. The matter has come to a critical stage; we are in want of help; you can give it to us. I am now on the wrong side of life according to the Indian standard of life. For me it can only be a matter of a few years, but future generations will look to your verdict and see whether you have judged wrong or right. The verdict is likely to be a memorable one in the history of the struggle for the freedom of the Indian Press. You have a heavy responsibility upon you. It is, I state again and again, not a personal question.” The jury of 7 Europeans and 2 Indians found him guilty 7:2. The Indian Press condemned the verdict and supported Tilak. The masses of people were outraged and the verdict led to the Bombay Textile Worker strike in 1908 which was brutally repressed. The working class as a whole came out to support Tilak. Lenin, writing of world events in 1908 said “There Is no end to the acts of violence and plunder which goes under the name of the British system of government in India…But in India the street is beginning to stand up for its writers and political leaders. The infamous sentence pronounced by the British jackals on the Indian democrat Tilak…this revenge against a democrat by the lackeys of the money-bag evoked street demonstrations and a strike in Bombay.” Gita Rahasya and Karma Yoga Tilak was sentenced to prison in Myanmar for a period of 6 years. It is here that his philosophical ideas found full expression with the writing of his commentary on the Gita, Gita Rahasya. It should be noted that Tilak wrote this book in utterly abject conditions. As Subhash Chandra Bose, who spent time in the same prison, wrote later, the prison would have unbearable heat in the summer, often get flooded during rains, and bitterly cold in the winter. Tilak was put virtually under solitary confinement in what Bose described as a cage. Tilak’s interpretation of the Gita is a work of genius. It shows Tilak’s vast reading in philosophy including Western philosophy. It should be noted that the central message of the Gita is Yoga, a word whose original meaning is the uniting of atman and brahman, of the individual soul with the soul of the cosmos. This is the path to moksha or liberation. Traditionally, different schools of thought have emphasized different paths to liberation but the most prominent ones had been the path of knowledge by Shankar and the path of bhakti or love/devotion by Ramanuja. Tilak instead proposed that the main message of the Gita was karma or the path of action. He proposed that the essence of the Gita was action, which was guided and united by knowledge and love. This action must not seek any reward for the individual self. It was in following the path of Karma Yoga that Tilak believed Indians would proceed towards Swaraj or self-rule. Tilak refused to believe that his religion taught a life of renunciation and meditation. He said “it is my thesis that Swaraj in the life to come cannot be the reward of a people who have not enjoyed it in this world…God does not help the indolent. You must be doing all that you can to lift yourself up…You should not, however, presume that you have to toil that you yourself might reap the fruits of your labour…Let us then try our utmost and leave the generations to come to enjoy that fruit.” As Mahatma Gandhi said in his own interpretation of the Gita, “This is the unmistakable teaching of the Gita. He who gives up action falls.” Therefore, Tilak, and Gandhi after him understood that religion in the best sense encouraged political action in the interest of truth, justice and freedom. The legacy of Tilak Today Indian society is deeply immersed in its history. The intense historical debates that our society faces are rarely about the past, they are essentially about our present identity. No period of Indian history is uncontested, seemingly every date of our texts is undetermined. Every debate on our history as it exists today can be traced back to colonialism and the subsequent freedom struggle. Our freedom struggle started the process of grappling with our history and every generation must revisit this quest anew. And yet today we are faced with a time when our freedom struggle itself, a seemingly incontestable inheritance, is being called into question. Indian intellectuals of varying ideological persuasions seem determined to belittle the mainstream of our freedom struggle. Further, our intellectual discourse suffers from a curious amnesia. Major events of our freedom struggle are discussed with almost no reference to British imperialism. The battle for our history is enmeshed with the battle of ideas. Our history is a weapon in this battle and a proper understanding of our freedom struggle is essential to move forward. The legacy of Tilak is important today because of his uncompromising struggle against western imperialism. His legacy is important because of his philosophical ideas which ask us to struggle for freedom in this world. His legacy is important because of his immense faith in the Indian people and India’s civilization. We must accord him the proper place he holds in the history of our freedom struggle. References Gita Rahasya (Hindi) by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, tr. Madhavrao Sapre Lokmanya Tilak A Biography by A. K. Bhagwat and G. P. Pradhan Bal Gangadhar Tilak, His Writings and Speeches The Bhagavad Gita According to Gandhi Reminiscences and Anecdotes of Lokamanya Tilak ed. S. V. Bapat Full & Authentic Report of the Tilak Trial published by N. C. Kelkar The Russian Revolution and India Ed. Ilasai Manian and V. Rajesh Inflammable Material in World Politics, V. I. Lenin

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

CategoriesArchives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed