|

By Catherine Blunt Great people are about great and mundane tasks. They are beacons of Hope lighting the way to a future for Humanity and enduring Positive Peace. E. S. Reddy was such a person whose life’s history also reflected the history of both the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa and its connection to the Indian struggle for National and Independence from the United Kingdom or Britain. It is a history of the two struggles on 2 different continents co-joined by the life and teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and his satyagraha movement of peaceful resistance which began in South Africa and moved forward to become the tool of passive resistance to British Colonial Rule in India and ultimately leading to the independence of India in 1946. E. S. Reddy’s life is also a narrative about struggle, courage, commitment, and solidarity with South African liberation forces seeking to end apartheid in South Africa and Namibia and the end to the neo-colonial rule at its core. According to Reddy, Mahatma Gandhi, while in South Africa and speaking about the inhumane treatment of non-whites / non-Europeans in South Africa, prophesied: "If we look into the future, is it not a heritage we have to leave to posterity that all the different races commingle and produce a civilisation that perhaps the world has not yet seen?" Gandhi’s remark foreshadows Martin Luther King, Jr.’s belief in a “Single Garment of Destiny” shared by all Humanity and his advocacy for a “Beloved Community” in which Humanity loves, shares, and protects and a ”World House” promoting world peace through peaceful coexistence and conflict resolution as the alternatives to war. Gandhi’s prophetic vision also anticipated a visionary like Martin Luther King, Jr. which he foretold during an interview with Howard Thurman, a remarkable and well-known African-American minister who led a group of Black Clergy to India in 1936: “he said with clear perception that he said it could be through the Afro-American that the unadulterated message of non-violence would be delivered to all men everywhere.” Clearly, Gandhi’s influence in the struggle against racism and injustice in South Africa, India, and throughout the world has had a profound impact on freedom and civil rights struggles in the United States which in turn has had an additional impact on the people of the world struggling for self-determination and liberation and in particular South Africa. E.S. Reddy, like his family, was influenced by Gandhi and the Indian struggle for Independence. All the E.S. Reddy stories and commentaries about him note that influence along with the same basic information about his life and his life’s work: the November 5, 2020, New York Times article by Sam Roberts, the South African History Online (SAHO) website, an E.S. Reddy interview in No Easy Victories, and during a 2018 interview with Archishman Raju, a member of the Saturday Free School. However, it was Ramachandra Guha, a historian and biographer introduced to Reddy by Gopal Gandhi, who sectioned Reddy’s life into 3 phases:

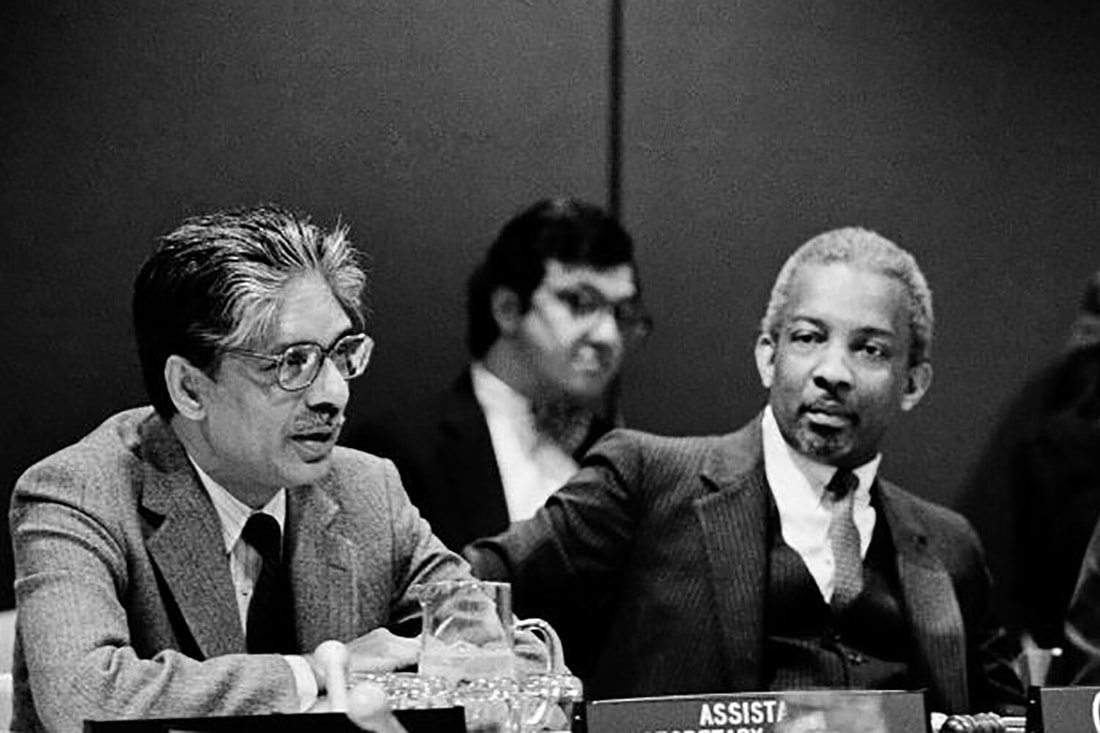

Phase 1. Growing Up and Getting Acquainted with South African Apartheid E. S. Reddy, was a celebrated Anti-apartheid advocate, a fighter for peace and a just world, and an avid Mahatma Gandhi Scholar was born in the Southern part of British India in July 1924 and died in Cambridge, Massachusetts in the United States (US) in November 2020 at the age of 96. He was born into an activist family of Gandhi supporters who were involved in the independence struggle to free India from British colonial rule. It is in that family, at that time and in that all-encompassing culture of national liberation with the influence of Jawaharlal Nehru, and through the Satyagraha teachings of Gandhi that E. S. Reddy learned about the commitment to the freedom struggle and the importance of solidarity with the struggling peoples of the world. It is because of that special and direct link between the early civil rights struggles of Indians’ living in the pre-apartheid, separatist Union of South Africa still under British control but governed domestically by a minority settler-regime of Dutch descendants or Afrikaners in 1910 and the Indians struggling for national liberation at home from Brittan’s official occupation and control of India beginning in 1858. It was Mahatma Gandhi, his method of struggle and movement of non-violent resistance against oppression and injustice or Satyagraha that he began and achieved success in South Africa that initially linked the two struggles when he returned home to India in 1915 and engaged in the struggle for national liberation against British colonialism using the same ideology and methods of struggle including building a mass movement of massive, non-violent resistance or satyagraha which ultimately led to Indian Independence in 1947. Mr. Reddy remarked in the No Easy Victories interview: " In India, in our generation, we're all influenced by Gandhi. So there is Gandhi under the skin ... We're influenced by Nehru. ... We wanted to have a society which is socialist, like Nehru wanted to have. So it was that kind of a radical outlook. ... Coming from that background, with both Gandhi and Nehru, ... we had a duty, not only to get India's freedom, [but that] India's freedom should be the beginning of the end of colonialism." Mr. Reddy completed his University studies in India in 1943 and a master’s degree in political science at New York University in the US in 1948 then attended Columbia University. He preferred living in New York City which allowed him access to news about home and South Africa. He became an intern at the United Nations in and in 1949 was hired as a political affairs officer. Originally, he frequented the Council of African Affairs because it gave him access to news weeklies from South Africa. Its members included Paul Robeson and W. E. B. Du Bois and the activities focused on anticolonialism and Pan-Africanism. Later, he became involved in Council affairs, with its members, and became friends with Alphaeus Hunton, the Council’s Director who did the research and wrote much of the educational pieces circulated. Reddy had frequent encounters with Robeson but only rare ones with Du Bois. However, both men and the organization also had a profound influence on helping prepare Reddy for his life’s work in the United Nations, especially with the newly independent Countries of Color who regarded him and his work as instrumental in the struggle against Apartheid in South Africa and Namibia (then called Southwest Africa). Of Alphaeus Hunton, Mr. Reddy said: “He did a lot of research, he published a bulletin, he published a book, he published a number of papers, pamphlets and other things. And he was the one, also, who kept in contact with the United Nations. There was a man called Chapman, Daniel Chapman, in the United Nations Secretariat at that time. And Alphaeus knew him well so he used to go to see him and through him make other contacts. Daniel Chapman—after Ghana became independent, he became the first ambassador of Ghana to the UN. Eventually and in retaliation for his anti-racism, anti-colonial work, Hunton was arrested by the US government which also banned the Council on African Affairs. This was in the early 1950s, during the McCarthy Era named after Senator Joseph McCarthy noted for his anti-Communist witch hunts against US citizens who were for peace nor war; who were for civil and human rights for US Black citizens, not economic, political, social, and cultural injustice; who were for unions, full employment, and decent wages, not unemployment, underemployment, poverty and starvation; who were for peaceful coexistence, not the US cold war and isolation of the Soviet Union. Hundreds were imprisoned and thousands lost their jobs. These experiences in the US among African-Americans struggling for their own freedom and the international struggle waged by People of Color to free themselves from imperialism, colonialism, and neo-colonialism added to the clarity of his vision and the determination of his purpose. Reddy’s growing knowledge about the liberation struggles of the African, Colored, and Indian populations in South Africa which through the Satyagraha Movement of Mahatma Gandhi linked the 2 countries (South Africa and India), linked their diverse populations, and linked the 2 struggles for freedom with his own youthful experiences growing-up under and resisting with his family British Colonial Rule over India. Reddy’s commitment to peaceful, non-violent action leading to “revolutionary change” was sealed. Phase 2: United Nations and the Struggle to end Apartheid in South Africa and Namibia Before retiring in 1985, Mr. Reddy had been a diplomat at the UN who led the anti-apartheid efforts at the UN’s Committee Against Apartheid. He was its Secretary from 1963 to 1965 and its Center Against Apartheid Director from 1976 to 1983. He also served as the Director of the UN’s Trust Fund for South Africa and the Educational and Training Program for Southern Africa. He used his various offices to campaign for sanctions against South Africa — economic and social-cultural boycotts. He also lobbied for the release of the African National Congress or ANC’s political prisoner, Nelson Mandela. He was appointed as the Assistant Secretary-General of the UN from 1983 until his retirement in 1985 using this opportunity to further educate and bring world awareness and attention to apartheid South Africa through seminars, international conferences, boycotts as well as providing scholarships to the families of South African political prisoners. Mr. Reddy commented to Archishman Raju in his 2018 interview about the substantive change in scope and effectiveness that occurred in the UN as more Nations of Color became independent and were admitted: “I was in the UN from 1949 and I didn’t think highly of the UN. It gave enough money to buy my groceries. UN was dominated by the western countries at that time. It was a sort of neocolonial space. By 1963, the composition changed, many African and Asian [nations] became members. These countries now constituted a large majority. That also affected some of the secretariat which was dominated by rich countries which could make large contributions to the budget. When the Special Committee against Apartheid was set up, my director, my supervisor, wanted to be secretary. He asked me if i wanted to be deputy. I said, No I don’t agree with you. But then the Western Countries decided to boycott the committee, he lost interest. The head of the department, a Soviet ambassador, offered me the job. I accepted and said, You are giving me a lifetime job because South Africa will not become independent unless all of Africa becomes independent. There is so much foreign involvement – economic, political, military - in South Africa. That proved true, South Africa became independent after I retired. “Now my job and my convictions were identical. I found a great satisfaction in the job but also a determination to do the best. There was also a feeling that as an Indian, I should do the best.” The No Easy Victories introduction explained Mr. Reddy’s role thusly: “From 1963 to 1984, he was the UN official in charge of action against apartheid, first as principal secretary of the Special Committee Against Apartheid and then as director of the Centre against Apartheid. When he retired in 1985, he had achieved the rank of assistant general secretary of the United Nations. “Beginning with his position as secretary of the Special Committee Against Apartheid, and in the face of opposition from the Western powers, Reddy facilitated the work of the small countries who were members of the Committee and who had taken up the responsibility of working to end apartheid. It was Reddy who supplied them with suggestions for action, draft resolutions, speeches, and reports. As director of the United Nations Centre against Apartheid, he played a key role in promoting international sanctions against South Africa and organizing the world campaign to free Nelson Mandela and other political prisoners. Recognizing the importance of public action for the effectiveness of the United Nations, he worked with and supported anti-apartheid movements around the globe. He [brought a] special insight to the discussion of support movements for African liberation in the United States because he saw numerous organizations at work over more than 40 years. He observed the power of American racism to influence not only U.S. government policy but also the support movements themselves. Throughout, he used the resources at his disposal to help bring an end to apartheid.” And his first involvement happened as a result of his affiliation with the Council on African Affairs which he frequented and became involved. At an early age and in his various roles at the UN, Reddy traveled all over the world and gained many friends especially in the international struggle against apartheid especially after 1970 when the Committee received a larger budget. Reddy traveled as a part of the UN Delegation to and in Europe (Western and Eastern) and in Africa to meetings with foreign ministers, heads of state, and conferences providing and collecting information about anti-apartheid struggles. They even hosted conferences as well as seminars which led western countries to begin to support sanctions against South Africa: “…we had many conferences and seminars organized, maybe about 40 organized. There you get the anti-apartheid movements and others in many countries. So even the Western countries slowly—in the beginning none of the Western countries supported sanctions. In the beginning it was very hard to get any Western country to vote against South Africa. But later smaller countries started changing. And in the '60s, first the Nordic countries, the Scandinavian countries, and then other Western countries like Netherlands and others started changing, becoming more friendly, contributing money for the prisoners and so on, saying that sanctions are good but that everybody should agree, although nothing would happen but at least they agree in principle. Which meant, we are trying to get them on our side, to isolate the few countries which had the most trade with South Africa and most military contact with South Africa and so on. And so that strategy worked.” E. S. Reddy’s life, experiences, and observations confirm for him and through him confirm for Humanity’s ability to push through and beyond man-made obstacles intended to interfere with, derail, and/or shackle human progress. Imperialism, colonialism, and neo-colonialism are those obstacles used by Western countries to dominate and subjugate the vast world of Countries of Color. Reddy’s Anti-Apartheid work in and beyond the UN is about defending and building world peace through peaceful struggles against colonial exploitations and exploiters like Gandhi’s Satyagraha as practiced in Apartheid South Africa, in colonial India, in the Civil Rights Movement in the US, and the BDS Movement against Apartheid Israel. For his work and vision, E. S. Reddy was acknowledged universally and won many awards as well as citations, especially for his work in the UN. It is clearly understood and he is regarded as the person whose efforts and contacts shaped UN policy against Apartheid in South Africa and Namibia as well as greatly influenced the international movement of boycotts and sanctions against apartheid. When he passed November-2020 at 96 years old, his death was announced by the President of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, who hailed E. S. Reddy’s “commitment to human rights” and his epitomizing “social solidarity,” as reported by Sam Roberts of the New York Times. Sean MacBride, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize and former United Nations commissioner for Namibia and quoted in No Easy Victories said of Mr. Reddy: "It has been my privilege to work with E. S. Reddy for close on 20 years, and ... there is no one at the United Nations who has done more to expose the injustices of apartheid and the illegality of the South African regime than he has. E. S. Reddy has done so with tremendous courage and ability. ... He dedicated his entire energy and skills to the liberation from oppression of the people of Southern Africa. He had to face many obstacles and antagonisms, coming from the Western Powers mainly, but he had the skill, courage and determination necessary to overcome the systematic overt and covert opposition to the liberation of the people of Southern Africa." Phase 3: E. S. Reddy, the Researcher, Gandhi Scholar, and an Archivist of Gandhi and Anti-Apartheid Artifacts During his retirement, Mr. Reddy researched and wrote about the early history of Anti-apartheid Movements, Black Liberation, and the linkage between the Indian and South African liberation Movements. He was a consultant to the ANC of South Africa, helping to develop historical documents and assisting with the UN Collection of Anti-apartheid artifacts. He also became a renowned Gandhi scholar, focusing on the links between the Indian and South African Liberation Movements. Mr. Reddy, in his Gandhi research, discovered documents indicating an early relationship between Gandhi and the formation of the precursor to the African National Congress of South Africa (ANC): the South African Native Congress created by 4 African Lawyers representing African organizations in South Africa. Mr. Reddy says by 1906 Gandhi was a non-violent revolutionary and a mass leader who had ceased petitioning the South African regime for civil rights. He had moved on to mass, direct, non-violent action and had become increasingly interested in the struggles of the African people of South Africa, “sons of the soil,” whose lands were to be confiscated. Gandhi supported the creation of the South African Native Congress, met with its major founder, Seme, and its President Dube, whom he introduced to the then President of the Indian National Congress of India visiting South Africa at the time. Accounts of these meetings were published in the Gandhi Newspaper. Mr. Reddy also edited Gandhi and South Africa 1914 -1948 with Gopalkrishna Gandhi as well as researched and wrote about members of Gandhi’s movement in South Africa like Thambi Naidoo and his Family and Kasturba Gandhi and the Satyagraha in South Africa - its roots and examples. E. S. Reddy described himself this way: “Well, I wouldn't call myself a pacifist. At least at that time. Now I'm more of a pacifist. But in India, in our generation, we're all influenced by Gandhi. So there is Gandhi under the skin. So there is pacifism in the system. Then we're influenced by Nehru, who was a socialist. The younger people were greatly influenced by Nehru. So I would say I was radical. In terms of the type of struggle against the British to get freedom, we believed in mass struggle—Gandhi also believed in mass struggle. But [the emphasis for us was more on] organizing the workers, peasants and so on. We didn't have much spiritual attitude towards violence the same way as Gandhi. And we wanted to have a society which is socialist, like Nehru wanted to have. So it was that kind of a radical outlook. “Now I come to the United States. In '46, as I said, there was this movement in South Africa which was a combination of Gandhians and communists. So the South African struggle all through the years of the struggle, from '46 on, has been a combination of pacifists, communists, and various other types of people. It was a sort of united struggle. Our own struggle in India was also a united struggle, except at certain times during the war when the communists and the nationalists couldn't get along, had problems. So that was the outlook.” The world of committed people who are believers in and dedicated to the struggle for truth, non-violent solutions, and self-sacrifice or satyagraha see E. S. Reddy as a proud son of India who was the embodiment of the history he lived, witnessed, and helped to create. Catherine Blunt, Educator and Community Activist — Member of the Saturday Free School

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

CategoriesArchives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed