|

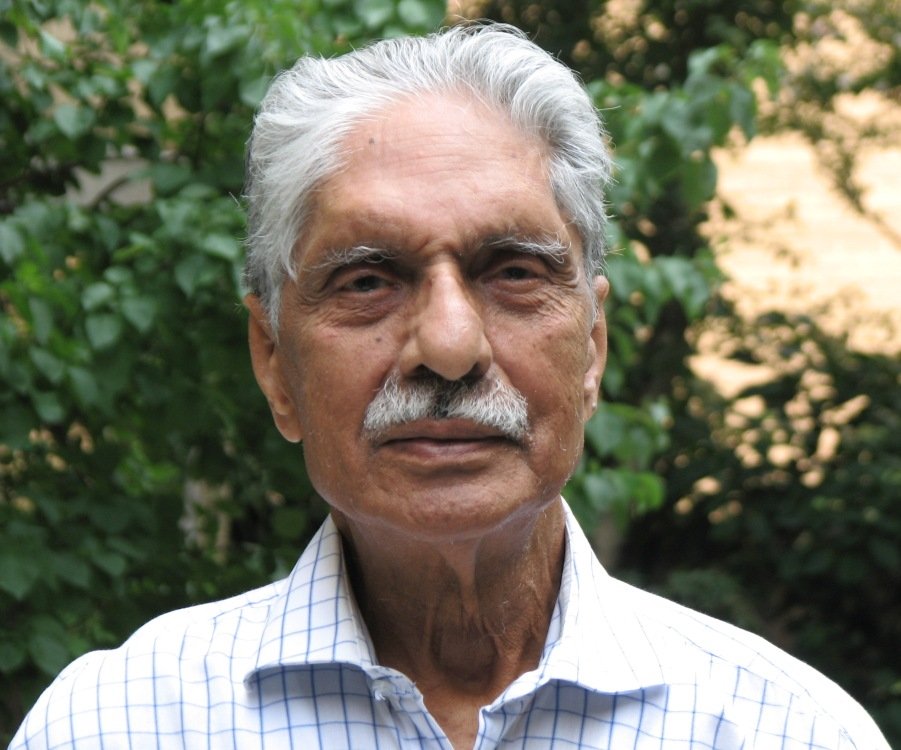

By Anil Nauriya  Enuga Reddy was an unfailing guide in my study of certain aspects of South African history and in relation to African liberation struggles in general. I had become familiar with the byline “E.S. Reddy” much before I came in personal contact with Mr Reddy. The New Delhi-based journal Mainstream often carried his articles on African struggles, Indians in Africa and related themes. From these I had become aware also of his distinguished contribution in various capacities at the United Nations and of his close connection with the anti-apartheid struggle. More than a quarter century ago I came across his book, Gandhiji’s Vision of a Free South Africa (1995), published by Sanchar Publishing House, New Delhi. It carried the following dedication : “Dedicated to Nelson Mandela and his colleagues in the struggle for a new South Africa where, in the words of Gandhiji, ‘all different races commingle and produce a civilization that perhaps the world has not yet seen’”. A few years had passed since the release of Nelson Mandela from prison and the struggle for building a democratic South Africa was on. Enuga Reddy’s dedication and articles linked this struggle to the hope that Gandhiji had expressed in his speech in Johannesburg on 18 May 1908. As Enuga Reddy had been keenly associated with the anti-apartheid struggle since the 1940s and knew personally the front-ranking African leaders associated with this struggle, I could hardly have had a more systematic introduction to the Indian interface with the African struggle than through the writings of Mr Reddy. It was from his 1995 work that I learnt about Gandhiji’s interaction with John Dube (1871-1946). John Dube had been praised by Gandhiji in 1905 as an African one should know for the work that he was doing for his people. Seven years later, in January 1912, when the African National Congress (then known as the South African Native National Congress) was founded in Bloemfontein, South Africa, John Dube was chosen as its first President-General. Dube’s Ohlange institution was based in Inanda very close to where Gandhiji had established his Phoenix settlement near Durban. It was also through Mr Reddy’s work that I became aware of Gandhiji’s association with the writer Olive Schreiner (1855-1920), an early critic of racism in South Africa. Enuga Reddy’s book contained a systematic analysis of the evolution of Gandhiji’s relation with African and Coloured leaders and support to their aspirations. Since the usual narratives on Gandhiji and South Africa were confined to the leadership that Gandhiji had provided to Indians in South Africa, Enuga Reddy’s writings were for me new and refreshing both in content and approach. Later I came across several other works by Mr Reddy that further evidenced the quiet and solid scholarship on Africa and on Gandhi for both of which he is known and universally respected. The books written or edited by him and his other writings were focused on outstanding leaders in the South African struggle such as Albert Luthuli, Oliver Tambo, Dr Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo, Molvi Ismail Ahmad Cachalia, G.M. (Monty) Naicker and Nana Sita. He published papers relating to the Treason Trial and about Indian efforts against apartheid. In addition, he brought together the speeches of the late Swedish statesman Olof Palme on the liberation of southern Africa. It was an education to read these materials. Enuga Reddy's continual efforts in this field outpaced many younger writers. He contributed a very comprehensive note on “Gandhiji’s contemporaries during his South African Sojourn” to Fatima Meer’s The South African Gandhi, published in 1996 by the Institute of Black Research, University of Natal, Durban. In 1993, the Navajivan Trust published his nearly-500 page long edited work (prepared in collaboration with Gopalkrishna Gandhi), Gandhi and South Africa (1914-1948). This covered an often over-looked aspect of Gandhiji : his continuing involvement with South Africa even after his return from Africa in 1914. More recently, in 2014, the National Gandhi Museum and Library published Mr Reddy’s paper “Thambi Naidoo and his family” bringing to the fore the great contributions that Thambi Naidoo had made in Gandhiji’s South African years. On the Indian struggle in South Africa during these years he later completed a work along with Kalpana Hiralal which too would be published by Navajivan. What I have mentioned here covers but a fraction of Mr Reddy’s huge corpus of writings and collections which have been published over the years. Mr Reddy’s meticulous concern for factual accuracy, eye for detail and his fairness in judgment make his writings a delightful read and provide a standard to aspire to. His work on the Sabarmati Register, that is the indexes maintained in Sabarmati Ashram, Ahmedabad of Gandhiji’s papers and correspondence has been a labour of love. When the National Gandhi Museum, New Delhi, sought to organize exhibitions to mark the centenary of the Gandhi-led 1913-14 struggles in South Africa, Mr Reddy sent long notes containing valuable information about the participants in these struggles and the various men, women and children who had been martyred or died in the course of the struggle. An affectionate and avuncular figure, ever helpful to younger scholars, Enuga Reddy has been more than willing to share information, answer queries, and educate, inform and guide those working on Africa and on Gandhi. My visits to South Africa were always preceded by exchanges with him in which he would make suggestions on who to meet and what to look for. There would be long lists of names of various remarkable people people in whichever city I was going to, complete with their backgrounds and the role they or their families had played in the anti-apartheid struggle, usually with addresses and phone numbers. Through these lists and notes he managed to convey to me some of the sacrifice and even thrill associated with the South African struggle. I had always envied Mr Reddy’s amazing energy and determined single-minded concentration on the work that occupied him at a given time. I had observed also his indifference towards those “chronophages” (to use Goethe’s term) who he considered undeserving of his time; naturally I was overjoyed and felt quite privileged when Enuga Reddy agreed to contribute a foreword to my little book, The African Element in Gandhi, published 17 years ago. I always rushed to him with my queries and he was always the first to whom I sent anything new I thought I found in the area of our interest, as in this extract from my mail sent to him in June 2007 : “ Meanwhile you'll be interested to know that I think I've solved the mystery of A Chessell Piquet's writings in Indian Opinion in 1911 etc. It happened by chance. I was re-reading Millie Polak's book and at one point she repeats H S L Polak's initials more than once. It then struck me : H S L ... H S L ...H S L ... A Chessell... As for Piquet, it is simply French for stake or Pole ... Polak. That also takes care of the articles signed A C P. Regards Anil PS: The interesting thing is that Polak was using A Chessell Piquet even in the late forties. A book review on the Indian question in South Africa in a scholarly journal in the forties is signed A Chessell Piquet.” I didn’t know Enuga Reddy was then recovering from a bout of chest pain, but he replied on the next day : “That is certainly strange and I did not know that you were a detective.” It must have amused him no end and before long he had told many others about my “discovery”. When I asked him about it later he wrote : “…I freely pass around my files.” That was so true and, having myself been a beneficiary of that trait of his, I could hardly complain! Anil Nauriya is a lawyer in the Supreme Court of India, a historian and writer.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

CategoriesArchives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed