|

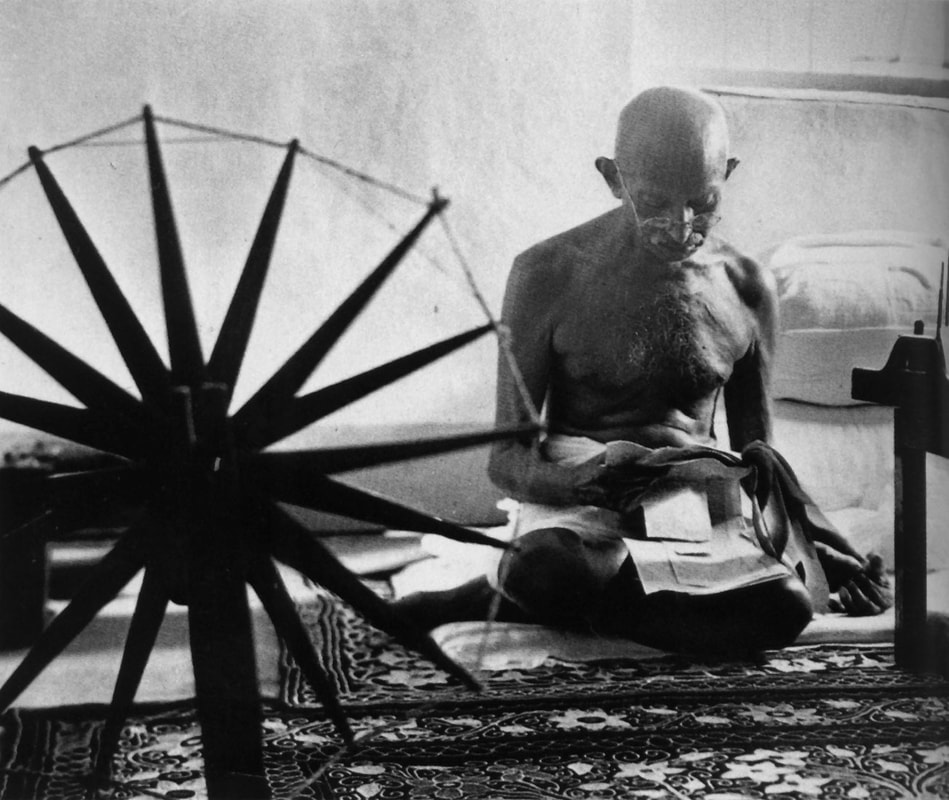

Purba Chatterjee The socialist ideal in India must reflect its unique objective conditions. India is the second most populous nation of the world, with vast diversity of religion, culture and language. Its economy is predominantly agrarian, and an overwhelming majority of its people live below the poverty line. Importantly, it is yet to recover from its long and brutal colonial past. As such, the essence of Indian socialism cannot be gleaned from a mere dogmatic reading of Marx, Engels and Lenin, nor can the Chinese or Soviet experiment be recreated in India. Insofar as socialism aims to uplift the workers and peasants and give them their rightful share in determining India’s destiny, any analysis of Indian socialism is incomplete without studying Gandhi, the great liberator of the Indian masses. Gandhi was the bone of the bone and flesh of the flesh of the Indian poor. As W.E.B Du Bois wrote in his review of Gandhi’s autobiography, “He studied Man. He travelled all over India and travelled in the dirty, crowded third-class so as to meet and know the masses. Probably no modern leader ever had so complete and intimate contact with and knowledge of the great mass of his fellows as Mohandas Gandhi. [1]” Gandhi’s vision of the modern Indian state was based on what he learned from his intimate engagement with the life worlds of the poor and working classes of India. While it is fashionable today to decry his views as puritanical, eccentric, and opposed to socialism, a careful study reveals that the essence of his beliefs carries the foundations of a socialist ideology that is specifically suited to the Indian context. For Gandhi, socialism underscored the ethical ideals of non-possession and service to humanity. Possession beyond one’s needs, especially when multitudes are deprived from even the humblest requirements, is akin to stealing. Every human being has an equal right to the basic needs of life and to a dignified and well-rounded existence. Every right an individual possesses however comes through the performance of duty--the duty of labour and service to his fellow human beings. It was Gandhi’s firm belief that enduring socialism could not be built by violent means. According to him, Bolshevism’s sanction of the use of force in expropriation of private property and maintaining state ownership of the same, foreshadowed its failure. However, he admired the tremendous courage of the Russian masses and their willingness to embrace great hardships for the sake of the noble Soviet experiment. He would write, “an ideal that is sanctified by the sacrifices of such master spirits as Lenin cannot go in vain: the noble example of their renunciation will be emblazoned forever and quicken and purify the ideal as time passes. [2]” Gandhi called for the destruction of capitalism without destroying the capitalist. The latter course of action would not benefit society. The wisdom of this becomes clear when we consider that an India impoverished by two centuries of colonial oppression, needed capital and industry to revitalise the economy and raise the living standards of its people. The struggle for freedom required a united front of capital and labour. Gandhi believed that the conflict of interest between the two could be resolved by the moral conversion of the possessing classes. He called on the wealthy to voluntarily become a trustee for the poor and place his surplus wealth at the disposal of the masses. The closest approximation of this ideal can be seen in present day China. In August 2021, President Xi Jinping declared that China had entered a new era whose guiding philosophy was common prosperity for all. This marks the end of the period of globalisation and market-based reforms that was adopted to bring forth rapid economic growth after the devastation of the cultural revolution. The current emphasis of the Chinese state is on increasing the earning potential of low-income groups, making regional development more homogeneous, revitalising the rural economy, promoting people-centred growth, and encouraging wealthy individuals and enterprises to return more of their earnings to society at large. The Chinese model demonstrates that a people’s socialist state can work towards a more equal society while coexisting with capitalists and enforcing a form of trusteeship of the rich. To Gandhi, the project of socialism was intimately linked to the task of raising the consciousness of the individual. This entailed furnishing the working class and peasantry with a substantive political education that allowed them to recognize their own dignity and worth to society. Just as capital is power, so too is labour, and only an enlightened worker would have the moral courage to stand up to those that tried to deprive him of the fruits of his labour. Gandhi believed that a revolution of values rooted in civilization was the basis for India’s freedom, not just from the economic exploitation of colonial rule, but also from the colonisation of the mind of Indians by western modernity. Civilization to him meant “that mode of conduct which points out to man the path of duty. [3]” Western civilization prioritised material advancement over moral progress, held bodily welfare and comfort as the primary object of existence and enslaved humanity to money and decadence. It encouraged acquisitiveness, greed and conflict between men and between nations. In contrast, the emphasis of Indian civilization, according to Gandhi, was on the spiritual growth of man, the evolution of the human soul to higher ideals of truth and justice. “The supreme consideration is man”, he would assert, and in the moral transformation of the individual based on her ancient civilizational values lay the path to true progress for India. The centrality of the human being also formed the basis of Gandhi’s views on modern machinery. While not opposed to machines as such, he maintained that “The machine should not tend to make atrophied the limbs of men [4]”, whose development and well-being should be the primary concern of the industrial progress of any nation. He recognized that factories of mass production and imported machine made goods had taken away jobs from the working masses, and allowed a few to get rich on the backs of millions who were impoverished beyond sustenance. In a colonial economy, the profits accrued from modern machinery never found its way back to the worker, who laboured under dismal and often dangerous conditions for a mere pittance. The link between unemployment and poverty under colonial rule was painfully clear to Gandhi. He rejected the claim that the Indian working class was poor because it was ‘unskilled’, saying “It is my conviction that India is a house on fire because its manhood is being daily scorned, it is dying of hunger because it has no work to buy food with. Khulna is starving not because the people cannot work; but because they have no work. [5]” The path to India’s salvation, thus lay in rejecting the mad rush for mechanisation and instead developing her innumerable cottage industries, starting with the charkha. Gandhi wrote “A humanitarian industrial policy for India means to me a glorified revival of hand spinning, for through it alone can pauperism, which is blighting the lives of millions of human beings in their own cottages in this land, be immediately removed. [6]” To this he added the voluntary renunciation of foreign goods by every Indian as part of the struggle for freedom. On this question, Gandhi was opposed by Rabindranath Tagore [7], the great poet of India, who believed that given the low cost of imported cloth, asking people to buy local cloth amounted to seeking a lowering of their standard of living. Gandhi answered that the welfare of an individual could not be separated from that of his starving neighbour, who needed work. Rejecting the lure of foreign cloth would not just increase domestic employment, but also instil a sense of pride in Indians and reinforce feelings of community. Then as now, true India lived in her seven lakh villages, and Gandhi saw that the rural poor must form the foundation of her democratic ideal. The self-sufficient village community was the fundamental unit of the Independent Indian state envisioned by him. Each such unit was to be a complete republic - it would achieve food security, grow and spin cotton to clothe its inhabitants, have compulsory education for its children and maintain theatres, public halls and playgrounds for recreation and cultural enrichment of the people. All activities would be conducted on the co-operative basis, with every man and woman contributing their quota of manual labour and service to the collective. Inter-village relations would be based on non-competition and mutual cooperation, directed by the principles of ahimsa (nonviolence) and satyagraha (insistence on truth). The Indian state must not become a behemoth, Gandhi insisted, crushing under its weight the crores of peoples who constituted rural India. Instead, it must derive its authority from the village unit, in which the real power would be vested. He professed complete political and economic autonomy for each village, and with the village at its centre, Indian society was to be organised in “a series of ever widening circles, not one on top of the other, but all on the same plane so that there is none higher or lower than the other. [7]” Gandhi rejected the assumption that a return to village life was regressive and antithetical to the progress of humanity. He believed that the ideal village of his vision would produce a new kind of human being - intelligent, imbued with the spirit of service and sacrifice for the common weal, and modern in the sense of holding his own against anyone in the world. Assassinated in 1948, Gandhi did not live to see his ideal of the independent Indian state brought to fruition. Nehru, who Gandhi chose as his political successor, deeply respected his leadership and total identification with the masses. However, he differed with Gandhi’s vision for the independent Indian state, as a series of letters exchanged between themi in the late months of 1945 bring to light [8]. Nehru believed that India needed technical advancement and rapid mechanisation to meet the emergent needs of feeding and clothing its impoverished millions. He also did not see a purely rural economy to be in keeping with the modern world. Under his able leadership the Indian state made significant strides towards social justice for the Indian people and did much to uplift the depressed classes. Through planning, industrialization, land reforms and redistribution, and the nationalisation of banks, the foundation for a modern, sovereign state was built on the ruins of colonialism. However, in the last years of his life, Nehru began to recognize what Gandhi had foreseen - that the gains of industry and mechanisation had been slow to reach the rural poor. Speaking to parliament at the mid-term appraisal of the third five year plan, one of the very last speeches Nehru was ever to give, he said “I begin to think more and more of Mahatma Gandhi’s approach … however rapidly we advance in the machine age and we will do so—the fact remains that large numbers of our people are not touched and will not be touched by it for a considerable time. Some other method has to be evolved so that they become partners in production even though the production apparatus of theirs may not be efficient as compared to modem technique, but we must use that, otherwise it is wasted. That idea has to be borne in mind. We should think more of these very poor countrymen of ours and do something to improve their lot as quickly as we can. [9]” The legacy of Mahatma Gandhi provides for our times the example of a revolutionary leader who dedicated his life to achieving a deep understanding of his people and their aspirations. He studied Indian society and institutions with the sophisticated technique of a scientific sociologist. He believed that India had a duty to provide a radical alternative to a world groaning under the tyranny of what he called the “monster-God of materialism”. He was never dogmatic in his beliefs however, and his thought continuously evolved in step with the movement of the masses. Nevertheless, he asserted that the ideal had to be worked out in theory and then used as a guiding light, a yardstick for measuring progress. While progress towards the ideal could be slow, it was not acceptable to lose sight of the goal. Neither was it acceptable to dismiss the ideal as impossible or utopian, as that would be an insult to the infinite creativity and potential of humanity. Gandhi had prophesied that western civilization, unless it underwent a moral transformation, carried the seed of its own demise. Today we are seeing this come to pass, as the west grapples with one of the most profound social, political and economic crises humanity has ever seen. This is most visible in the U.S. where a minority elite, morally bankrupt and contemptuous of physical labour, lives in obscene decadence while the majority of American citizens struggle to make ends meet. Unemployment and poverty is at an all time high in American society, and its community and educational institutions lie in shambles. Capitalism and liberal democracy, which the west has tried to export, both face an existential threat as suffering workers rise in revolt against the ruling elite. Western advocates of socialism focus on narrow identity politics and promoting ‘wokeness’, instead of a serious attempt at restructuring society and the economy. Ironically, they take great pains to clarify that theirs is a ‘democratic’ socialism, as opposed to the ‘authoritarian’ socialism of Russia and China. They either cannot or do not care to examine why there are no respectable jobs for the working class, and why the people of the richest and most powerful nation in the world are so poor and degraded. They ask the worker to be satisfied with handouts and charity, robbing him of his dignity. In the final analysis, democratic socialists stand for neither democracy nor socialism, but for maintaining the status quo behind the smokescreen of a false moral superiority. Even more alarmingly, today the west is gearing up for a ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’, a ‘Great Reset’ that threatens to enslave humanity even further to machines and technology, and end human life as we know it. Increased automation, elimination of schools to make way for virtual education platforms, algorithm-based generation of news, and more sophisticated surveillance and biosecurity measures for state control over the people, are only a few of its long list of diabolical designs. The intention behind this anti-human ‘revolution’ is clear- it seeks to eliminate the working class altogether, create a world system that serves only the ultra-rich, and fundamentally alter what it means to be human and how human beings relate to one another. These are dark times. The crisis of the west is more than just economic and political, it is a crisis of values, of a moral grounding of society. The people of the world are clamouring for a way out, for restoration of their humanity. The workers of the world want jobs, they want to earn an honest living and live with dignity. They want to give their children a substantive education and a meaningful future. They have to be lifted from poverty and illiteracy and given their rightful share in the building and running of their societal institutions. It is our moral imperative today to break with western models of democracy and socialism, and redefine the ideological content of these institutions so that they once again serve humanity. For India, this is a time for introspection and searching. We must not allow ourselves to be ideologically subservient to the declining West. We must revisit the essence of Gandhi’s socialist vision, and creatively reinterpret it for our times. Socialism and democracy in India has to be a bottom up process, and derive its authority from the working masses. The humble Indian peasant who sustains us with his life-giving labour, is deserving of the highest respect and privilege in society. It is the betterment of his lot that is the task at hand for India today. The project of socialism calls not just for economic planning, but also a revolution of values from a thing-oriented to a people-oriented society. In undertaking the monumental task of building true socialism in India, let us remember Gandhi’s talisman “Whenever you are in doubt, or when the self becomes too much with you, apply the following test. Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man whom you may have seen, and ask yourself, if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him. [10]” References[1] Du Bois, W.E.B., Review of Gandhi's Autobiography [2] Gandhi, M. K. Navajivan, 21 Oct. 1928; Young India, 15 Nov. 1928 [3] Gandhi, M. K. Hind Swaraj, 1909 [4] Desai, Mahadev. ‘A Student’s Four Questions’, Young India, 13 Nov. 1924 [5] Gandhi, M. K. ‘The Great Sentinel’, The Mahatma and the Poet, 2005 [6] Gandhi, M.K. ‘A Student’s Questions’, Young India, 17 Dec. 1925 [7] Gandhi, M.K. The Hindu,1 Aug 1946; Harijan, 4 Aug. 1946 [8] Letters 39, 40, 41 in The Selected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (Vol. IV) : Selected Letters [9] Nehru, Jawaharlal. 207, Selected Works, Series 2, Vol 84 [10] Gandhi, M. K. Mahatma Gandhi - The Last Phase, Vol. II, 1958 Purba Chatterjee is a post doctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania and a member of the Saturday Free School. She is also an organizer of the Year of the Freedom Struggle, an effort to commemorate India's 75th year of independence in Philadelphia.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

CategoriesArchives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed