|

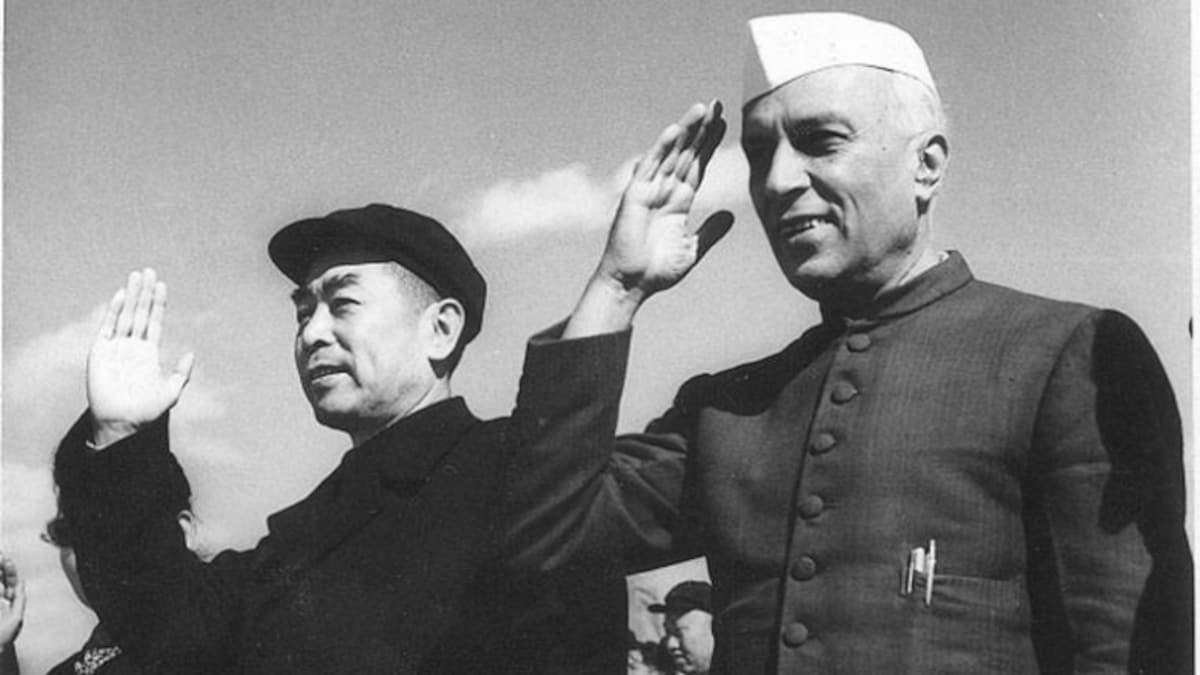

Archishman Raju  Both China and India have experience of long yesterdays of our past history and in our subconscious selves we carry the memories of hundreds of generations with all that they have to teach, of joy and sorrow, of strength and weakness, of wisdom and folly. Our waters run deep. We are not froth and foam on the surface, which vanish when strong winds blow. So we shall pass from the ever-changing reality of today to the reality of tomorrow, when we shall hold our own again, not subject to the whims of others. In that reality to come, India and China will hold together This opening quote by Jawaharlal Nehru, written in the middle of the Second World War, serves as the inspiration for this article [1]. Despite the difficulties that have since then inflicted on the relationship of these two civilizations, Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision was essentially correct and is extremely relevant for the future. World relations have moved far beyond the times when Nehru wrote this statement. Today, China is competing with the West ideologically and technologically. It is offering a model of an alternative social and political system that does not have to bend to the Washington Consensus. By 2050, China and India are projected to be the world’s two largest economies. The relationship between these two countries is hugely important for the future of the world. Thus, to see what kind of new future the world will witness, we must not just examine the trajectory of these countries, but further provide a positive vision for the future. To see what kind of global order they will shape requires that we see their founding moments in the modern era, and assess the visions that shaped those moments. In 1949, Mao Zedong announced to the Chinese people, “I hereby declare the establishment of the People’s Republic of China”. One year later, India was declared to be a sovereign democratic republic by its leadership. Two new nations were coming into existence and had to decide the character of the state which would govern their people. They had both been the outcome of two long parallel but very distinct struggles, a non-violent revolution in India against British imperialism, and the struggle against Western domination and Japanese imperialism alongside a violent civil war in China. The struggle against imperialism in India and China and the founding of the modern state constituted two great experiments in society, which has perhaps no parallel in history. Both countries had extremely large populations, of about 340 million and 550 million respectively at that time. Further, they had to govern a large land-mass of several million square km, with China about three times bigger than India. They had old civilizations and old traditions which had faced a shock from the entry of western colonialism. The drain of wealth and de-industrialization combined had further created a reactionary local ruling elite which collaborated with imperialism. These two revolutionary movements were thus faced with an enormous task of reconstruction, 1) Building the Economy, 2) Uniting the Country while dealing with the contradictions within society and 3) Fighting External Threats coming from Neocolonialism. The leadership of both of these movements chose to construct a socialist state and society to combat these challenges. Faced with crushing poverty, they both aimed to create a society that was free of exploitation. To understand these two experiments, it is necessary to more fully theorize the transition to socialism. Some theoretical considerations must be taken into account to truly understand the nature of this transition in India and China. First, one must see these transitions as part of a break from the system of world imperialism. This requires theorizing and understanding the true nature of the world system that oppressed the people of India and China. For this, we must refer to W.E.B Du Bois and his idea of a color line. Du Bois most fully theorized the idea of a white supremacist world system [2]. Du Bois was a great admirer of both the new China and the Indian Independence Struggle. He saw these two experiments as breaks in the chain of this system. Second, the transition to socialism can not be seen in purely economic terms. It is necessary to consider it in political terms and to examine the role of the state and the nature of political power. Even in Lenin’s writings after the Russian Revolution e.g. in “Left-Wing Childishness” and “On Cooperation”, Lenin was concerned with upholding the state even if economic concessions to private ownership were made. The question is not simply what forms of the economy exist in a society, but rather whether political power lies with the people or not and whether the state is responsible to the people. Finally, one must see the transitions in India and China as consistent with their civilizational heritage. That is, the socialist state in India and China would be a modern but non-European state. This requires going beyond the ideas of European enlightenment including its radical wing. The idea of a modern state that is distinctly non-European in character terrifies the western world. It is nevertheless an idea whose time has come. Theorists like Alexander Dugin and Zhang Weiwei have been emphasizing the non-European character of Russian and Chinese society which is reflected in the nature of their state. In opposition, theorists like Francis Fukuyama and Amartya Sen have tried to find European enlightenment values in Asian traditions and oppose the idea of any distinctly Asian values. I hold the view that distinct civilizations must be taken into consideration but further one must struggle for inter-civilizational unity. Further, I hold that the anti-colonial struggle has a pre-eminent place in terms of our interpretation of this civilizational heritage. India offers a very clear example of that in the ideas of Gandhi and Tagore. Finally, I reject the western conception that India belongs with the west because it is a “democracy”. Instead, I argue that there are different paths to democracy and socialism, and there are commonalities in the challenges and processes that shaped the Indian and Chinese transition to socialism. On the surface, the political path that they chose was very different. However, to see the Chinese government as being based on the Soviet model and the Indian government to be based on the western democratic model is a very shallow reading. Both sets of people were trying to establish a modern state which was compatible with their own unique domestic condition. There were certain differences in the trajectory of Indian and Chinese societies that necessarily created differences in the form of the state, and in the kinds of challenges that they had to face. At the same time there were similarities in outlook as they struggled against common challenges. Every experiment faces challenges, it encounters difficulties and failures, but to ruminate on the faults is to miss the enormity of what was attempted, and the difficulties that stood in its way. Both states were the product of a century-long struggle for emancipation. Both states set out explicitly to create a socialist society as well as a new kind of democracy. Building Socialism: The Two Paths Much is made of the differences between India and China during the initial period of state building. These differences are amplified and stretched by western commentaries which see these two nations as fundamentally dissimilar. Yet, the first Indian ambassador to China, K. M. Panicker would note that New China represented the “culminating event of Asian resurgence”[3]. A comparison between the writings of Jawaharlal Nehru and the Chinese leadership in the years immediately following the creation of the new state and before Mao’s adventures reveal certain essential similarities in attitude towards the challenges the state faced. In 1950, Zhou Enlai would say that China’s “state-owned economy is still very small, and the private economy that is beneficial to the national economy and people’s livelihood has a certain positive role. It should be supported for its development.” [4] Liu Shaoqi, Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong in this early period put forward the idea of a slow transition to socialism, the need for constructing a new democracy, the need to discover a uniquely Chinese path to socialism and further the weaknesses in a society so bereft of capital and facing such extreme poverty. They emphasized land redistribution, the construction of cooperatives and the need for national planning. China decided to adopt a multi-party system with political consultation under the leadership of the Communist Party of China. They strove to develop a people’s democratic dictatorship. Jawaharlal Nehru came under intense criticism in India for not going fast enough. He ceaselessly tried to explain the need for a slow transition to socialism. He was, in principle, for nationalization of industry, but he repeatedly emphasized that the state did not have the capacity to handle all industries. Furthermore, he argued that fully nationalizing industry at an early stage would have inhibited the productive capacity of the nation, which it was so essential to build. Nevertheless, the Industrial Policies Resolution of 1956 laid down a series of key industries which would be state owned. One of the initiatives of the post-independence Indian state was the Planning Commission set up to constitute the Five Year Plans. To be able to plan in a society like India, it was first necessary to study it. It is for this reason that India established one of the world’s foremost statistical architectures to study society under the leadership of P. Mahalanobis. This remarkable attempt is little known but in fact was one of the first attempts to try to systematize the study of a former colony with the purpose of planning for its development. Zhou Enlai spoke with Mahalanobis on his visit to India and invited him to China. Subsequently, Mahalanobis visited China, lecturing and interacting with planners. In turn, several Chinese scholars visited India to understand the statistical method being used [5]. The Nagpur resolution of the Congress in 1959 put ceilings on land holdings and also heavily encouraged cooperatives in farming. The Indian government had been interested in implementing cooperative forms and had learnt from the Chinese experience in this regard. In 1957, an official Indian delegation visited China and closely observed the cooperative farming experience around the country. They made a very enthusiastic assessment of the success of Chinese cooperatives and laid down a set of recommendations for the formation of cooperatives in India [6]. India was a very diverse country which had been partitioned at independence. It constantly faced challenges of being divided based on linguistic or regional lines. China was a multi-ethnic country with a majority Han population but was also conscious of being divided along ethnic lines. Therefore, the constitution of India declares India to be a Union of States, not a Federation. Nevertheless, it gave a level of autonomy to the various states in its constitution. The Indian leadership worked out a unique solution to the contradiction of unity as well as diversity in the nation. The Chinese leadership also rejected the idea of a Federation instead choosing a people’s republic which would have multi-ethnic unity [4]. A necessary condition for building socialism was the question of peace. In this regard, the joint Panchsheel initiative that India and China came up with continues to be visionary. The five principles, mutual respect, mutual non-aggression, mutual non-interference, equality and mutual benefit and peaceful co-existence did not just apply to India and China, but to international relations in general. As the two prime ministers said in their joint communique, “If these principles are applied not only between various countries but also in international relations generally, they would form a solid foundation for peace and security”[7]. These principles were later adopted at the Bandung conference and passed at the UN General Assembly. One should not underestimate the achievements in health, in literacy, in the building of scientific institutions and in the development of basic industries that were achieved in these two countries. Finally, the most important part of the building of a new society was the creation of a new man and a new woman. This was the golden age of culture when many of the great poets, writers and artists were created from the struggle and put forth the vision of a new human being. Difficulties and Challenges Both states however faced several challenges and difficulties in their initial experiments of socialism. Though much was achieved in India including the abolition of the zamindari system and implementation of a set of land reforms, the full land reform agenda was ultimately stalled. Similarly, despite the enthusiasm around cooperatives, elements of the Congress did not allow its implementation at the State level. Why could the Congress not fully implement its program? The first reason was the composition of the Congress itself which conducted various ideologically different wings in it, a fact that came to the fore after Jawaharlal Nehru’s death and the splitting of the Congress under Indira Gandhi. The second was the administrative apparatus, including the judiciary and the bureaucracy which did not support the program and actively opposed it in several cases. To this must be added the role of the media which was often heavily influenced by western commentaries and doomsday predictions about the country. These so-called pillars of democracy in fact often worked to actively inhibit true democracy in the country. The First Amendment to the Indian constitution and the debate between Jawaharlal Nehru and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee on the occasion is testimony to the difficulties the land reform agenda was encountering, and the need felt to curtail freedom of speech [8]. These contradictions played out even further during Indira Gandhi’s period. In China, on the other hand, there were attempts to accelerate the economic development of the country beyond what was possible. The resolution adopted at the Sixth Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in 1981 evaluated the history of the 30 year period after the party took control of the state. After the party abandoned their initial line of a slow transition to socialism consistent with the objective nature of economic underdevelopment in the country and instead tried to subjectively accelerate development, it led to several errors “characterized by excessive targets, the issuing of arbitrary directions, boastfulness”. This led to Mao’s erroneous theory of continuing revolution and the near disastrous effects of the cultural revolution. The resolution of the eleventh central committee however holds the collective leadership to be responsible for these theoretical and practical mistakes, and particularly calls out “careerists like Lin Biao, Jiang Qin and Kang Sheng”. The resolution, in no uncertain terms, condemns Mao’s theses on the cultural revolution and calls it “entirely erroneous”. After the cultural revolution, the party had been reduced to such a weak state, that Deng Xiaoping was forced to make certain compromises to stabilize the party and continue its rule. India also faced several challenges from imperialist nations in this period, including the arming and development of Pakistan as a neocolonial hostile state at its borders, the weaponization of food aid, foreign-funded sectarian movements for balkanization. To this must be added, the assassinations of leadership which severely weakened the state. In this context, the India-China War must also be put down as an erroneous step initiated by Mao and must be understood alongside its erroneous foreign policy which supported reactionary forces in Chile, Bangladesh, Iran and Angola and aligned itself with the United States. Continuing and Completing the Old Vision Ultimately, however, to excessively harp on the difficulties of the post-colonial state is also to commit an error of not recognizing its achievements. The fall of the Soviet Union, along with two assassinations greatly accelerated the unraveling of the Indian state and it was forced into compromises with the West. Since then, that initial vision has not been fully recovered. However, to see these backward steps as a total destruction of the initial vision is itself reactionary and denies the achievements of the anti-colonial struggle and the effect it had on the Indian people. The world situation today carries distinct possibilities. The Chinese government has eradicated extreme poverty and is emphasizing the goal of “common prosperity”. The decoupling of the West with Russia, as well as its slower decoupling with China signals the creation of a new global economic system where the supremacy of the dollar will be broken. The Indian intelligentsia and ruling elite is at a cross-roads. Will it decide to align itself with the future, which belongs to the darker peoples of the world? Will it continue and complete the task of building a socialist society? Or will it continue its alignment with the Western “democracy” and imperialism. To commit oneself to the West at this time is to sink in pessimism and despair. To recognize the possibilities of Asia and Africa is to proceed with optimism, which derives from faith in the majority of the world’s people, and work out the trajectory of completing the vision of the anti-colonial struggle and the building of a socialist society with distinctly Indian characteristics. References [1] Nehru, Jawaharlal. Selected Works Series 1 Vol. 12 (December 1941-August 1942) [2] Monteiro, Anthony. "Time, Space and Race: On Clarence J. Munford's Race and Civilization." The Black Scholar 34.3 (2004): 53-65. [3] Panikkar, K.M. In two Chinas: memoirs of a diplomat. London, Allen, 1955. [4] Qian, Zheng. An Ideological History of the Communist Party of China Vol. 2, Royal Collins, 2020. [5] Ghosh, Arunabh. "Making It Count." Making It Count. Princeton University Press, 2020. [6] Patil, R. K., et al. Report of the Indian delegation to china on agrarian co-operatives. Planning commission, Government of India Press, New Delhi,, 1957. [7] Nehru, Jawaharlal, Selected Works Series 2 Vol 26 (June 1954-September 1954) [8] Singh, Tripurdaman, and Adeel Hussain. Nehru: The Debates that Defined India. HarperCollins UK, 2021. Archishman Raju is a contributor to and an editor of this journal.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

CategoriesArchives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed