|

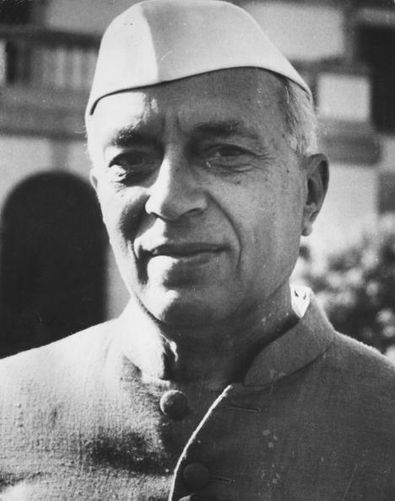

Jeremiah Kim When we speak of the life and legacy of Jawaharlal Nehru, of his role in the Indian freedom struggle, and of the immense task he faced as the country’s first Prime Minister in building an independent state from 1947-1964, we do not do so in a vacuum. The global order is undergoing an epochal shift, opening a field for dialogue about new and evolving state-forms across the non-Western world. Simultaneously, the United States is wracked by an unprecedented loss of popular faith in the government and its ability or willingness to represent the interests of ordinary people. Such conditions present us with the question of what a truly democratic society might look like, not merely in name but in substance. In seeking to answer this question, there is much we can learn from the past. What would it have looked like if Martin Luther King Jr. had lived to lead the Civil Rights Movement toward a more complete transformation of the American state? On the other hand, what path might India take in an emerging multipolar world? By examining the life of Nehru, we can see glimpses of possibilities that still lie before us to achieve in our time. A democracy born from struggle Born in 1889 as the first son of Motilal Nehru, a successful lawyer who would play an important role in the freedom struggle, Jawaharlal Nehru grew up in a sheltered, relatively privileged household. At the age of 15, he was sent to school in Britain, where he would eventually study to join the law profession like his father. As part of a select upper class of Indians educated in the West, Nehru could have easily become a cog in the machine of British imperialism. His life instead took a different path. Returning to India in his early twenties, Nehru took an interest in the Indian National Congress, which at the time was politically aimless and dominated by elite and middle-class liberals who were cut off from the masses. The arrival of Mahatma Gandhi, fresh from his struggle in South Africa, transformed the trajectory of the Indian anti-colonial movement as well as Nehru’s own life. Nehru became part of a cadre of freedom fighters who wholeheartedly accepted the leadership of Gandhi and his method of nonviolent mass struggle against British rule. Over the course of the next three decades, Nehru was imprisoned by the colonial government nine times and spent almost nine years of his life in jail, exemplifying the kinds of sacrifices that Gandhi called upon all of India to make in order to win their freedom. In his autobiography, Nehru described an early meeting between Gandhi and the Muslim League, seeking their participation in the non-cooperation movement, “His eyes were mild and deep, yet out of them blazed a fierce energy and determination. This is going to be a great struggle, [Gandhi] said, with a very powerful adversary. If you want to take it up, you must be prepared to lose everything, and you must subject yourself to the strictest nonviolence and discipline. When war is declared, martial law prevails, and in our nonviolent struggle there will also have to be dictatorship and martial law on our side if we are to win. You have every right to kick me out, to demand my head, or to punish me whenever and howsoever you choose. But, so long as you choose to keep me as your leader, you must accept my conditions, you must accept dictatorship and the discipline of martial law.” This raises a crucial point: Today, the Indian state is often propped up in contrast to other so-called authoritarian governments in Asia, particularly China. It is asserted that India is a liberal democracy just like the U.K. or the U.S., with the implication that Britain taught India how to govern democratically. This is a distortion which conceals a basic truth: that the foundations of the Indian state and its ideas of democracy were forged in the crucible of struggle against British rule. The British, for their part, believed that Indians were too backward to participate in democracy. Within the freedom struggle, democracy was defined not in formulaic or procedural terms, but based on the movement’s capacity to involve the Indian masses in a collective political process of struggle for higher aims of independence, economic justice, social progress, and spiritual revitalization. As a “dictator”, Gandhi did not suppress the masses but instead called forth the greatest expression of their democratic will, instilling them with the audacity to change the course of human history. From Gandhi’s example, Nehru and others learned that strong, central leadership was not antithetical to democracy, but actually necessary to enable the rule of the people. Nehru was indeed a democrat, but contrary to what some claim today, he was not one of the liberal or bourgeois variety. On this question, it is clear that Nehru underwent his own transformation. In his autobiography, Nehru acknowledged that his political outlook was “entirely bourgeois” as a young man. An encounter with the kisan peasant movement near his hometown in 1920 reversed his direction. Meeting men and women who were clothed in rags and ruthlessly exploited by landowners, Nehru admitted: “I was filled with shame and sorrow—shame at my own easygoing and comfortable life and our petty politics of the city which ignored this vast multitude of semi-naked sons and daughters of India, sorrow at the degradation and overwhelming poverty of India. A new picture of India seemed to rise before me, naked, starving, crushed, and utterly miserable.” But Nehru was not one to wallow in patronizing pity; instead, he traveled from village to village, “eating with the peasants, living with them in their mud huts, talking to them for long hours, and often addressing meetings, big and small.” This experience stripped Nehru of his youthful shyness; he learned to talk with the peasants straightforwardly from the heart. Contacts with world movements Nehru became a man obsessed with the idea that Indian independence must do justice to the forgotten, immiserated masses of India’s countryside — people who, until the arrival of Gandhi, were completely ignored by the nationalist movement. This moral and political commitment was given a new dimension when Nehru visited the Soviet Union in 1927. There he met revolutionaries such as Soong Ching-Ling of China and Diego Rivera of Mexico along with countless Soviet officials, workers, and peasants. Nehru sensed immediately that the Russian Revolution had ushered a new world into existence. He also noted that conditions between Russia and India were similar — both were “vast agricultural countries with only the beginnings of industrialisation” — and if the Soviets found a solution for these problems, it would make India’s work easier. That same year, Nehru attended the International Congress against Imperialism in Brussels, where he found common cause with representatives from the growing anti-colonial movements of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Before a crowd of representatives of these movements, he described how Britain’s stranglehold on India was also used to enforce the suffering of other countries, with India serving as the primary base of the British Empire and Indian troops being sent to put down rebellions in countless colonies. India’s freedom would therefore not only remove an intolerable weight from the shoulders of the Indian masses; it would also lift a barrier that had been imposed against the liberation of humanity. Here the seeds were laid for India under Nehru’s leadership to play its pivotal role in the project of reconstructing the world order in the wake of colonialism. Needless to say, Nehru’s thinking was profoundly impacted by what he saw in his travels around the world. In particular, the Soviet experiment opened up new possibilities and methods for overcoming enormous problems that had been created by imperialism and were thus unprecedented in India’s long history. Along with contemporaries like Subhas Chandra Bose, Nehru moved definitively toward socialism as the path forward for India, and worked to popularize socialist ideas among the Congress and the people. At the Congress’s 1931 session in Karachi, the party defined its vision of a post-independence economic policy that included state ownership of key industries and resources, protections for workers, and economic relief for peasants. Nehru understood that the world was undergoing fundamental changes; India must not be left stranded in the dark as humanity surged forward. It was with this in mind that Nehru wrote his famous 1933 essay, “Whither India,” in which he posed a simple question to the wider independence movement: Whose freedom are we striving for? Either the freedom struggle would remain stuck in a narrow nationalism that upheld a status quo of exploitation by elites, or it would keep pace with new forces of history and work definitively in the interests of India’s peasants and workers. “Leaders and individuals may come and go,” he wrote, “but the exploited and suffering masses must carry on the struggle, for their drill-sergeant is hunger. … Is our aim human welfare or the preservation of class privileges and vested interests of pampered groups? The question must be answered clearly and unequivocally by each one of us. There is no room for quibbling when the fate of nations and millions of human beings is at stake.” Although Gandhi and Nehru differed in their points of view on some issues, particularly the question of industrialization, they were fully united on fundamental principles, including the revolutionary power of nonviolence, a deep understanding of the masses, and their ultimate goal of bringing about the highest intellectual, economic, political and moral development of every man, woman, and child. Consequently, Gandhi named Nehru as his political successor and as the protector of the legacy of the Indian anti-colonial struggle. When the time came for India to honor its “tryst with destiny” at the dawning of independence in 1947, Nehru poured himself into the task of stabilizing the country and constructing the Indian state. From the Indian Constitution’s Directive Principles, to the establishment of Five Year Plans and the abolishment of the zamindari system, to the expansion of both public education in schools and political education through elections, Nehru formulated and created pathways for all of India to move toward goals of socialism, national development, and social progress. New India and the Bandung spirit One of the most noteworthy features of the new Indian state under Nehru’s leadership was its commitment to world peace. India at the beginning of the Cold War was viewed as too weak to play a major part in world affairs by the United States, inheriting their attitudes from the British. For his part, Nehru emphasized that a strong Indian state was needed for the country to resist becoming a pawn of the West and contribute to peace and detente on the international level. Indian diplomacy played a key role in facilitating negotiations during the Korean War, helping to pull the world back from the brink of disaster as U.S. leaders toyed with the idea of dropping atomic bombs all across China and Korea. And although India-China relations would fall through in the 1960s, it should be noted that India backed the People’s Republic of China in its claim to UN membership and a seat on the Security Council. In this vein, Nehru instilled a uniquely Gandhian spirit toward the Indian state’s principles of world peace and self-determination. This spirit shaped India’s participation in the 1955 Bandung Conference, which boldly asserted that the newly independent nations of Asia and Africa could act as a moral force on the stage of world history by throwing their collective weight on the side of peace. Ideologies at the conference varied, ranging from a few U.S.-aligned countries to communist-led states like China and North Vietnam, and it was no small task to even bring so many leaders together at the height of the Cold War. Largely behind the scenes, Nehru worked to the point of exhaustion to find points of unity that all 29 attending nations could agree upon. Bandung was simultaneously a radical leap forward for human thought and global democracy, and a catalyst for wide-ranging experiments with socialism and state governance across the Third World. Together, the leaders at the conference formulated that world peace was the most pressing need for the peoples of Asia and Africa to develop out of colonial backwardness. Bandung also established a precedent and a line of communication for these nations to engage in substantive, friendly dialogue about their respective economic and political systems — free from the mediation of the West. Here, countries of socialist and other orientations could coexist and learn from each other. As Nehru saw it, the new states of Asia and Africa must cooperate and carefully decide their forms of rule, in order to fulfill the promises of their anti-colonial struggles and play their rightful part in building a more peaceful, just world order. During a session of the conference, Nehru made plain, “I have come here not merely as an individual or representative of India, but as a part of the revolutionary process that has been going on in India; for I am a child of that revolution. I am no static person; I have been in the marketplace; I have moved with crowds and seen the vast squalor and the poverty prevailing and so I feel strongly about these matters.… We stand everywhere in the world, more so in Asia, on the sword's edge of the present dividing the past from the future…. We should be careful to preserve the hard-won freedom we have got, careful to see that it is not crushed out of existence.” Later at Bandung’s closing session, he concluded, “We met because mighty forces are at work in these great continents, in millions of people, creating a ferment in their minds and irrepressible urges and passions and a desire for change from their present condition…. The very primary consideration is peace. You and I, sitting here in our respective countries, are all passionately eager to advance our countries peacefully…. We came here, consciously and unconsciously, as agents of a historic destiny. And we have made some history here and, we have to live up to what we have said, and what we have thought and even more so, we have to live up to what the world expects of us, what Asia expects of us, what the millions of these two continents expect of us. I hope we will be worthy of the people’s faith and our destiny.” In the coming years, Nehru became a key architect of the Non-Aligned Movement, which enabled these new countries to devise their own independent foreign policy amid the Cold War — a vital necessity with the United States breathing down their necks and demanding absolute fealty as it still does today. Aghast at these developments, Western media deployed frenzied propaganda portraying India’s foreign policy as either naively idealistic or “rabidly pro-Soviet”; this campaign would crystallize into outright sabotage and attacks against Indira Gandhi as she built on the foundations laid by her father. Conclusion: Nehru, India, and the nature of freedom Taking all of this into consideration, we can see that Nehru’s great task was to translate the experience, vitality, and vision of the anti-colonial movement into a new way of governing India. If India’s path to socialism differed from that of the Soviet Union or China, this was not a result of mental weakness or timidity from Nehru. Neither would Nehru allow India to be used as a cudgel against other socialist states, since he always maintained that each country had the right to determine its own form of governance. For India, the centrality of nonviolence in the freedom struggle led to the natural conclusion that the country must attempt, as far as possible, to achieve a peaceful transition to socialism. Nehru thus embarked on a quest to develop a living synthesis of Gandhian nonviolence and Indian civilization with ideas of socialism, modernization, and foreign policy. This was a unique experiment in human history. It may be true that Nehru made some compromises or mistakes in this endeavor. However, we must center in our minds the fact that he and his comrades were attempting to design and institutionalize a state to uplift 400 million people against almost impossible odds. Nehru himself was often the first to admit internal faults and failures; what should inspire us is the fact that he did not let these setbacks cripple him to inaction, and that he always strived to refine his thinking and action in close contact with the Indian masses and with the wider movement of humanity. Nehru’s profound achievement was that he laid the foundations for the Indian state to work toward eliminating poverty, overcoming illiteracy, politically and morally educating the people, achieving a socialist pattern of society, realizing national unity out of diversity, and contributing to world peace. If the state ever ceased to strive toward these goals, then it would break its social contract with the people and in his eyes, India would no longer be free. From Nehru, we learn that freedom is not a static, abstract value frozen in time; freedom must have a direction for the people, must breathe life and motion into their aspirations for a common future. Perhaps no person can better sum up the meaning of Nehru’s leadership than Martin Luther King, who wrote after Nehru’s death in 1964, “It would be hard to overstate Nehru’s and India’s contributions in this period [of the Cold War]. It was a time fraught with the constant threat of a devastating finality for mankind. There was no moment in this period free from the peril of atomic war. In these years Nehru was a towering world force skilfully inserting the peace will of India between the ranging antagonisms of the great powers of East and West. … Nehru’s example in daring to believe and act for peaceful co-existence gives mankind its most glowing hope. […] In this period my people, the Negroes of the United States, have made strides toward freedom beyond all precedent in our history. Our successes directly derive from our employment of the tactics of nonviolent direct action and noncooperation with evil which Nehru effectively employed under Gandhi’s inspiration. […] My people found that Satyagraha, applied in the United States to our oppressors, also clarified who was right and who was wrong. On this foundation of truth as irresistible, a majority could be organized for just solutions. In all of these struggles of mankind to rise to a true state of civilisation, the towering figure of Nehru sits unseen but felt at all council tables. He is missed by the world, and because he is so wanted, he is a living force in the tremulous world of today.” References

Jeremiah Kim is a writer, activist, and a member of the Saturday Free School.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

CategoriesArchives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed