|

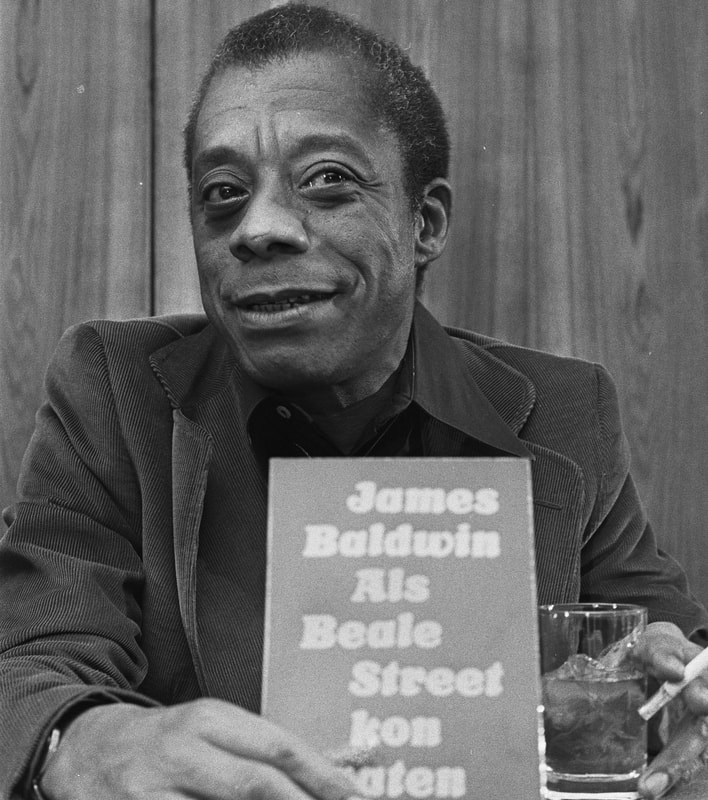

by Archishman Raju  Part 1: My Introduction to James Baldwin I still have vivid memories of the first time I reached the U.S., having arrived, for my PhD, in upstate New York at Cornell University. I remember being a little afraid and a little bit in awe, whether I admitted it or not. Many of the famous intellectuals who I had heard about, or whose books I had read, would be wandering in these corridors. The huge library put to shame anything in my past educational experience. The pace of work was faster than anything I had been used to. The most difficult part of the adjustment, however, was the social atmosphere. I didn’t quite know what to talk to people about, or how to talk to them. The content and tenor of conversations was very different from what I was used to. I was not quite sure how much to extend myself, and what I saw as friendly gestures were politely rebuffed. My experience was typical, so much so that the university kindly gave us a document “explaining” this in our orientation. This document proposed a “wall theory”. As per this document, Americans tend to be more friendly in their initial meetings with a low barrier or wall while “other cultures” (assorted) tend to be more reserved with a higher wall. For Americans (also assorted), these walls tend to become higher and it is more and more difficult to get close to them. For the rest of the world, apparently, the walls become lower and once you have crossed an initial barrier, you quickly become friends. Leaving aside the content of this explanation, I was then in no position to appreciate where such blandness in explanation derived from. Being interested in politics, I searched vainly for some signs of what I recognized as political activity in the University and found very little. I signed up online for a purportedly socialist group whose website I had encountered before coming to the U.S. The local branch of the socialist (Trotskyite) group turned out to be exactly one individual, who took me to a gathering in New York City. I don’t remember much of it except that I somehow remember that it was all white men. When I was introduced to the leader, he looked at me in what I, perhaps unfairly, remember as a leering way. They were interested that I write for their magazine. I didn’t know why they would be interested in me because it seemed to me we had disagreed on practically everything. Truths that I held to be self-evident, like the fact that Fidel Castro was a man to be admired, they held to be a sign of being “pseudo-left”. It was my first introduction to the American left, which was like nothing I had seen before. On the way back home we switched to uncomfortable silence and “small-talk” and they laughed at the way I pronounced “thermometer”. I never met them again. I did not know it then, but these initial experiences were my introduction to “the white world”. In one way or another, most Indian immigrants in the U.S. are first introduced to the U.S. through the white world. This is certainly true of those going as professionals but it is also ultimately true of those who go in search of low paying service jobs. This produces one of two responses: either they tend to stick together and remain in the Indian community or they work hard to successfully “assimilate” into American society. Indians have been one of the most successful examples of assimilation in American society. They are the richest ethnic group in America today. They are CEOs of companies, endowed chairs in Ivy League Universities. They are very visible as scientists, doctors and other professionals. This assimilation has come at a grave cost, both to Indians in the West and to Indians in India who tend to judge the West by what they think is the performance of these successful individuals. It was only when I spent time in Philadelphia that I got to see a very different part of America. Entering the Saturday Free School for Philosophy and Black Liberation held at the Church of the Advocate in North Philadelphia, the first thing I remember is the laughter. “If you want to feel humor too exquisite and subtle for translation, sit invisibly among a gang of Negro workers. The white world has its gibes and cruel caricatures; it has its loud guffaws; but to the black world alone belongs the delicious chuckle” says W.E.B Du Bois. It was a room primarily of older black people and even before any discussion started, I felt at home for the first time in America. The topic of discussion turned out to be the first chapter of Capital by Karl Marx. The Free School was my first introduction to the Black World and it introduced me to James Baldwin just as the 2016 presidential election neared. Philadelphia held the Democratic National Convention and also a “Socialist Convergence”. I participated in a “Black Lives Matter” march which, in the middle of a black neighbourhood in North Philly, seemed to mysteriously have mostly white people. The organizer called for “Black People at the Front” and “White People at the Back”. A black woman came out of her house and asked a black police officer “Now, what is that”. “Black Lives Matter, Ma’am”, he replied. “Now, I have my problems with that” she said. The reaction at my University to Donald Trump’s election was something to behold as huge marches appeared where there had been silence and “cry-ins” were held to commune in collective grief. It was in stark contrast to North Philly where there were no marches and life went on. I read The Fire Next Time just as I saw these two worlds in seemingly different realities. It was a book that I could not put down. I read it from start to finish in one sitting. I had not read anyone like James Baldwin. He explained more about American society than anything I had read. He helped me make sense of my own experience. “The Negro’s experience of the white world can not possibly create in him any respect for the standards by which the white world claims to live”. What struck me in reading Baldwin was not so much his description of the Black condition, but his description of the condition of white people. White people needed to be liberated, he said and black liberation was the price they would have to pay. Baldwin writes in a way that no writer in the English language does. He may be the greatest essayist in the English language. He analyzes society dialectically and does so through patient negation. His negation is forever optimistic, laying out a vision not just for a new society, but for a new civilization. He analyzes the Western world, and its foremost and most unlikely representative today, the United States of America. In describing my experience in the U.S., I am trying to lay out more than just a subjective viewpoint and a single experience. I am trying to argue that nothing in our experience in India prepares us to understand the complexity of the United States. Most definitely, nothing in our experience prepares us for the momentous changes that are taking place in the West today. Young Indian students who go to the West today have a very different experience than even those who went 10 years ago. More and more of them encounter a society undergoing convulsion in the throes of a crisis with economic, political and spiritual dimensions. They are witnessing the unraveling of a society which can no longer promise safety, comfort or stability. Assimilating into this decadence can not produce anything but spiritual discomfort. In writing that India Needs Baldwin, I want to argue that India needs to understand the West on its own terms. It needs to understand it, not through the pages of the New York Times, and the journals of various respectable American publications, but rather through learning from a tradition of Truth. It needs Baldwin not only for the sake of Indians in the West, but for the sake of Indians in India who deserve the truth about American society which influences so much of our discourse. Why was I so gripped by Baldwin’s writing? Outside of the quality of the writing, it reflected a need to understand the West. Every modern educated Indian has a foot in the western world, both because of our history and our present. What we are yet to realize is that the West needs us more than we need the West. Those who want to reject the West tend to try to retreat in their own culture. This is insufficient, for we can not reject what we do not understand and Baldwin’s writing gives us a framework to understand the ongoing changes in the Western World. Part 2: James Baldwin in Three Essays One must start reading Baldwin with The Fire Next Time. Baldwin’s philosophical style relates deeply with our own. “Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.” His philosophy is fundamentally based on a love for humanity. It is almost like reading the Buddha or Kabir in modern form. His style and philosophy derives from the black Church and the blues. It is not the blues or Baldwin that is introduced to Indians as American culture but rather it is mediocre “pop” music, or video games or TV shows. Baldwin finds little in American popular culture that is worthy of respect. “Something very sinister happens to the people of a country when they begin to distrust their own reactions as deeply as they do here, and become as joyless as they have become”. Baldwin ties the joylessness of this private life with American performance at an international level. “the American dream has therefore become something much more closely resembling a nightmare, on the private, domestic, and international levels. Privately, we can not stand our lives and dare not examine them; domestically, we take no responsibility for (and no pride in) what goes on in our country; and internationally, for many millions of people, we are an unmitigated disaster.” We may be familiar with America’s numerous imperial misadventures, particularly since Asia has been the recipient of so many of them (Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan..), but it is far more difficult to understand the system that produces these misadventures. It is not, as Indian communists like to argue, simply a matter of profits for the war industry in the U.S. The war industry is certainly important and war is profitable but, as Baldwin argues, America’s role in the world is the result of a system of white (or western) supremacy. The system changes and reproduces itself but retains an essence. In its latest iteration, it sometimes accommodates various colours at the top but it does not depart from the fundamental assumption that the future of the world must be determined by Western Civilization. The American ruling elite reacts hysterically to the idea of a world that does not have them at its center. This explains their reaction to China or the $100 billion they are willing to send to Ukraine. Nothing quite confirmed Baldwin’s writings as the reaction of the liberal elite to the election of Donald Trump. They immediately, without end and continuously for years blamed the election on Russia. Baldwin could have written for our times, “Behind what we think of as the Russian menace lies what we do not wish to face, and what white Americans do not face when they regard a Negro: reality” In denying the reality of their own bankruptcy, the growing anger of the American people as a whole, and the growing rebellion of white workers in particular, it was clear that the members of the American ruling elite were desperately hanging on to a fantasy that Russia was responsible for Donald Trump. Baldwin’s genius is that he turns the question of oppression around, by examining its effect of white people rather than listing the crimes committed on the black population. Baldwin unmasks the surface of American society and reveals what lies beneath it. He examines and rejects the standards of society. But in doing so, he also conducts a search for revolutionary possibilities in the American people—black and white. His is a search for new moral standards and for new human beings. In this sense, his quest is a universal quest. India needs Baldwin because there is something for us to learn from the west. To read Baldwin is liberating, it allows you to think in new ways and frees you from dogmatic understanding. Baldwin extends his analysis of white supremacy as a global system in No Name in the Street, reflecting on his experience in France. He expresses solidarity with the Algerian struggle against France and ties together the racial situation in America with the colonial situation around the world. He sees colonial subjugation not just as a means of material well being but as the key to European identity. The key to the identity is, for Baldwin, in the concept of the moral choice. That choice can not be made as long Europeans are bound by what they think is their history. Baldwin says “...it is not easy to see that, for millions of people, life itself depends on the speediest possible demolition of this history, even if this means the leveling, or the destruction of its heirs. And whatever this history may have given to the subjugated is of absolutely no value, since they have never been free to reject it;…That is why, ultimately, all attempts at dialogue between the subdued and subduer, between those placed within history and those dispersed outside, break down”. In speaking of the dialogue between the colonizer and the colonized, Baldwin is not talking about the polite debates that are held by the civilized representatives of the colonized in western halls. This dialogue will not be settled in the halls of the Oxford Union. Whenever a true dialogue begins, it must fundamentally challenge the state of western economic arrangements and the intellectual and cultural power of the west. The response, then, will not be polite patronizing applause but more akin to the treatment the West gives out to its official enemies: in Venezuela, Libya, North Korea, Iran and now China. It is in his last major essay, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, written in 1985 that Baldwin brings forth the sheer vastness of this thinking. The essay, written 2 years before his death, is written just at the beginning of a counter-revolutionary moment with Reagan in power in the United States and Gorbachev having been elected General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. “The situation of the Black American “minority” connects with the situation of the so-called “emerging” or “Third World” nations”, he says, “These existed, until only yesterday, merely as a source of capital for the “developed” nations. The “vital” interests of the Western world were the riches extorted from the colonies. Without this worldwide plunder, there could have been no Industrial Revolution.” None of the emerging nations, says Baldwin, have achieved economic autonomy. He compares independence in the third world, with integration in America. Both “merely set in motion a complex legal and political machinery designed to camouflage and maintain the status quo”. Thus, Baldwin analyzes the changing nature of the white supremacy in the form of a world system and continues to argue for the need for a fundamental transformation of this system. Baldwin analyzes white supremacy in the book in deeply historical but also civilizational terms. He speaks of the “European” as a term referring “to the dooms of Capital, Christianity and Color”. Baldwin sees the processes that are transforming the world, and, leading up to our moment will lead to an inevitable confrontation. “The Black man’s first encounter with the West...brought him devastation and death, we are only, now, beginning to recover, are beginning, out of the most momentous diaspora in human memory, to rediscover and recognize each other. This is a global matter, and the denouement of this encounter will be bloody and severe precisely because it demolishes the morality, to say nothing of the definitions, of the Western world.” Baldwin hints on two occasions in the essay that the Western ruling elite may be cowardly enough, may become so incapable of change that it would be willing to destroy all of life rather than cede to a new system. He sees a coming final crisis in this system of white supremacy. He says, “the American Dream can be taken as the final manifestation of the European/Western/Christian dominance. There are no more oceans to cross, no savage territories to be conquered, no more natives to be converted.” At the same time, he sees the possibility of a new civilization, liberated from the shackles which the western world has put on the world for the past few centuries. “The present social and political apparatus cannot serve human need”. He argues that the United States still contains revolutionary possibilities in its depths and has the potential to lead this liberation. “I know this sounds remote, now, and that I will not live to see anything resembling this hope come to pass. Yet, I know that I have seen it---in fire and blood and anguish, true but I have seen it.” Conclusion James Baldwin is a writer who has a message for humanity. He is a witness not just for black people in America but for the darker people of the world, and ultimately, for all of humanity. He speaks with an intimate knowledge that can only be gained by constant contact. He speaks as a creation of the Western World who does not accept Western values. In doing so, he furnishes a new epistemology and gives us a way to understand the meaning of the changes taking place in the world today. The Western world is watching India, and hoping that our “democratic” inheritance will pull us to their side in the reckoning that is to come. It would do well to remind us how many Indians were transported to the Caribbean, or how many lives were wasted in man-made famines which is part of the historical record of western “democracy” in India. We will certainly grow more powerful but we can not become “great” by imitating a people who barely recognize our existence. There is a civilizational connection between India and Black America that is yet to be fully uncovered, reflected in one of the most remarkable connections in 20th century history: between the Indian and the black freedom struggle. Reading Baldwin is like reading an old friend, who speaks in a language that Indians are familiar with from their own philosophy. And yet Baldwin belongs to the modern world, and his subject matter is its most technically complex creation, the United States of America. His examination enlightens a revolutionary path forward for our time. Archishman Raju is a contributor to and an editor of this journal.

1 Comment

Meghna Chandra

2/19/2024 10:03:30 am

Thank you for your courage and candor, Archishman Raju. Your analysis of Baldwin through the lens of your experience is so clarifying for people of all colors. You show how Baldwin demystifies American Empire more powerfully than a so-called Marxist analysis. You inspire me to read James Baldwin, and in doing so, learn more about myself.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

CategoriesArchives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed